Hail to the Helix

National DNA Day Celebrates Genomics Coming of Age

BY MICHAEL TABASKO, OD

The NIH Catalyst is commemorating 30 years of publishing with a series of updates to past coverage. In this issue, we highlight the evolution of genomic research at NIH.

CREDIT: NHGRI

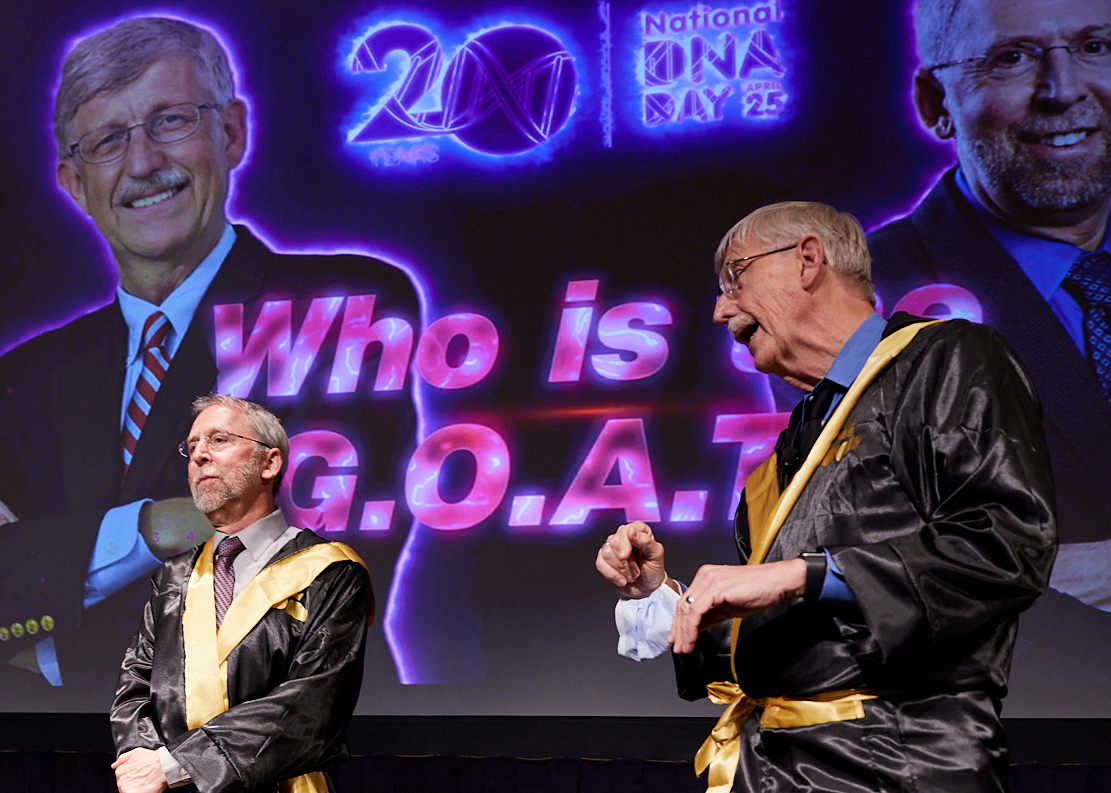

DNA Day 2023 featured thought-provoking discussions about the present state of genomic research and even dared to entertain with a spirited competition between former NHGRI (and NIH) Director Francis Collins and current NHGRI Director Eric Green, to determine who is the G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time) NHGRI director.

Like the elegant double helix itself, DNA Day 2023 at NIH wove together intersecting threads. “Threads of discovery from basic science and threads of necessity that spring from human disease,” said Lawrence Brody, Director of the Division of Genomics and Society at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), to kick off the 20th Anniversary Symposium at Lipsett Auditorium. National DNA Day was designated by Congress and is recognized annually on April 25 to commemorate the successful completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) in 2003 and the discovery of DNA's double helix in 1953. The day celebrated those intersecting milestones and featured thought-provoking discussions about the present state of genomic research—even daring to entertain with a spirited competition between former NHGRI (and NIH) Director Francis Collins and current NHGRI Director Eric Green to determine who is the G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time) NHGRI director.

Links to the April 25 agenda and archived videocast are at https://www.genome.gov/event-calendar/NHGRI-National-DNA-Day-20th-Anniversary-Symposium.

Genomics research across NIH

The March–April 2003 issue of the Catalyst highlighted Green’s vision for genetics research as the newly minted NHGRI Scientific Director. He predicted that the coming era would be defined by “figuring out what are the best ways to use the fruits of the HGP for doing research into human genetic diseases.” The ensuing years have both enhanced our understanding of who we are and provided fresh challenges. Now as NHGRI Director, Green moderated a panel discussion at DNA Day about how the HGP and NHGRI have influenced research across NIH.

CREDIT: NHGRI

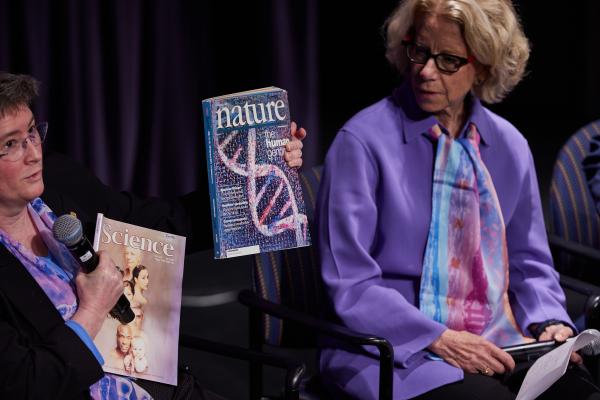

NCATS Director Joni Rutter holds up two of her treasured mementos, original copies of Nature and Science from February 2001 highlighting the publication of a working draft of the human genome, as NICHD Director Diana Bianchi (right), co-participant in a panel discussion, listens.

Human development

At the start of life, genetic testing has the potential to diagnose a myriad of disorders. However, gaps still remain in our knowledge of gene expression during human development, and it is imperative to understand developmental gene expression in the placenta, in the fetus, in the young infant, and throughout childhood, according to Diana Bianchi, Director of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Bianchi spoke about the importance of trans-NIH collaborations, such as the Developmental Genotype-Tissue Expression project.

Partnerships have long existed between NICHD and NHGRI. A collaboration between Green’s lab and NICHD two decades ago identified a gene responsible for a common form of inherited deafness. At that time, Green was dreaming about "what’s going to be one of the largest zebrafish facilities in the world,” he said to the Catalyst (March–April 2003, page 6). Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have since become an important model organism to study human genetic diseases. In 2012, a state-of-the-art zebrafish core was built, and NIH-wide research has since uncovered the genetic underpinnings of several human health conditions including cholesterol metabolism and human growth anomalies.

Fueled by tech

On the heels of the HGP’s completion, NHGRI was eager to tackle hard problems. “How do you grapple with massive data sets, study thousands of genes all at once, and mine this information efficiently to find genes that are implicated in human disease?” Green asked. (March–April 2003, page 6). Technology, it turns out, was the answer.

Josh Denny, Chief Executive Officer of the All of Us Research Program, touched on the staggering leaps in technology that have fueled the genomics boom—advances in cloud computing, data storage, and access to electronic health records have been transformative. Moreover, sequencing costs have fallen from “billions to hundreds,” said Denny. Still, access to all those data pose new questions, such as how to take complex data and make it useful and transparent to health care providers.

CREDIT: NHGRI

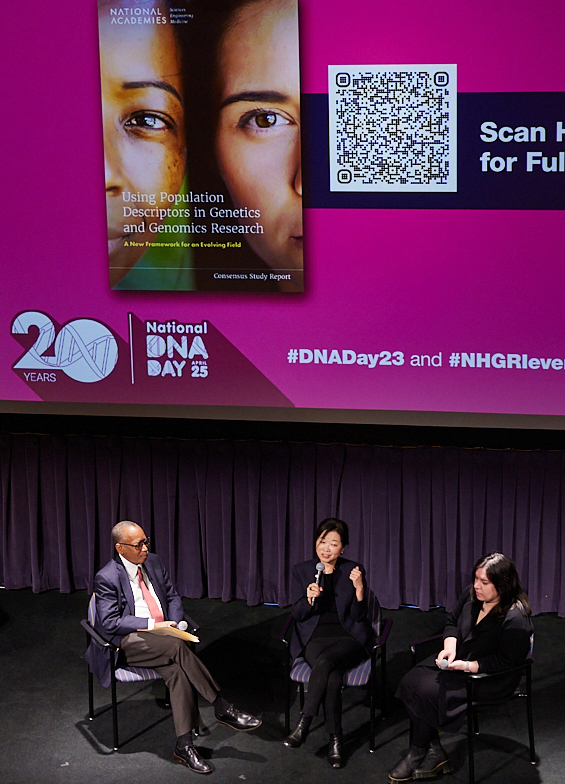

NHGRI Acting Deputy Director Vence Bonham, Jr. asked Columbia University’s Sandra Soo-Jin Lee and Genevieve Wojcik of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health how genomic research can be strengthened by more accurately describing people and the things that have an impact on their health.

Not just genes

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Director Gary Gibbons studies racial health disparities in cardiovascular disease. Before coming to NIH in 2012, he was one of the first extramural investigators to receive funding to study changes in the epigenome in cardiovascular biology.

“Why do African Americans have a higher risk of hypertension?” Gibbons once asked his Harvard Medical School professor. That professor urged him to explore the genetic component, even if other factors were at play. Gibbons did just that, and he reflected on how partnerships with NHGRI have been instrumental in understanding the molecular basis of diseases such as hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, and has now informed precision medicine programs. He has a deep appreciation of how other factors—the proteome, microbiome, and exposome—interact with gene expression. Gibbons established a new protocol called GENE-FORECAST, which is the Genomics, Environmental Factors and the Social Determinants of Cardiovascular Disease in African-Americans Study.

From A-T-C-G to the clinic

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Director Joni Rutter remarked on the exciting evolution of gene therapy, particularly to treat rare conditions caused by gene mutation. Indeed, NCATS was born from the HGP; it was founded in 2011 to usher basic science findings through the translational-science pipeline. Notably, the Early Translation Branch, formerly known as the NCATS Chemical Genomics Center and originally the NIH Chemical Genomics Center, was created in 2008 to translate the HGP into biology and disease insights leading to new therapeutics.

Rewind to 20 years ago, and then-new NHGRI Clinical Director William Gahl was interested in rare diseases “beyond just knowing what the gene is, [but] being able to develop therapies.” (March–April 2003, page 4). Gahl created the Undiagnosed Diseases Program in 2008 (September–October 2010, page 1), which grew into a worldwide model one decade later (May–June 2021, page 14).

Rethinking population descriptors

Researchers and scientists who use genetic and genomic data should rethink and justify how and why they use race, ethnicity, and ancestry labels in their work, according to a new National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report. In a separate DNA Day session, researchers who contributed to that report discussed how we can strengthen genomic research by more accurately describing people and the things that have an impact on their health.

“Identify categories that really address the questions you’re asking,” said Columbia University’s (New York) Sandra Soo-Jin Lee. Lee urged investigators to resist typological thinking and assuming that groups are discrete categories. Genevieve Wojcik of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Baltimore) cautioned that descriptors in population genetics often lie along lines of race. “If you’re using race as a surrogate for environment, maybe you should be measuring the environment,” she advised.

CREDIT: NHGRI

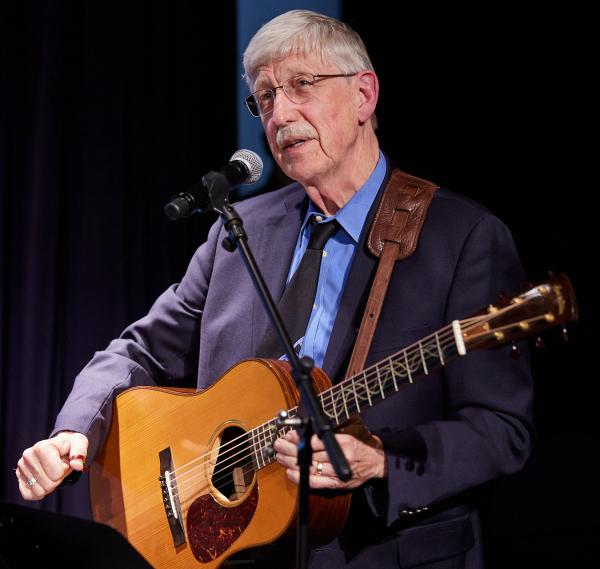

It wouldn't be a proper NHGRI event without music. To conclude the day’s events, Francis Collins, the G.O.A.T., delivered the 2023 Louise M. Slaughter National DNA Day Lecture. And of course, he was accompanied by his guitar.

To conclude the day’s events—but not before the audience voted him G.O.A.T. in a nail-biting tiebreaker—Francis Collins delivered the 2023 Louise M. Slaughter National DNA Day Lecture. And of course, he was accompanied by his guitar.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, July 11, 2023