Battling Blood-Sucking Bugs

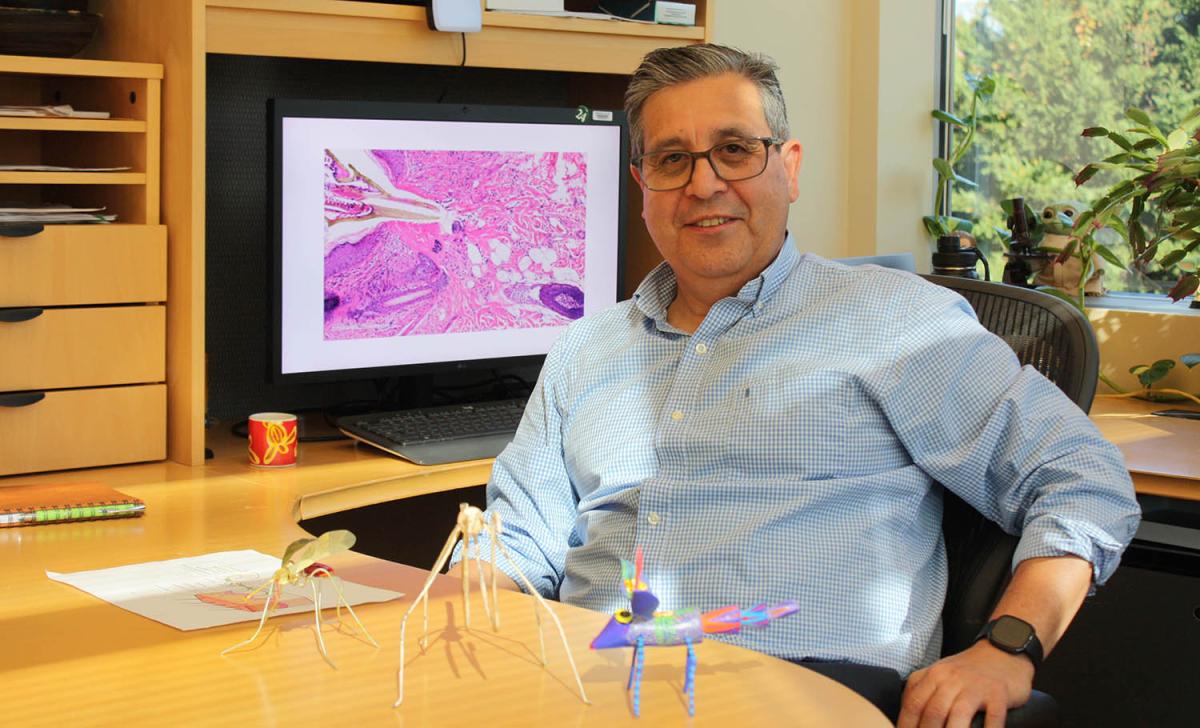

Jesus Valenzuela dissects how our bodies react to insect bites.

On a visit to the NIH Clinical Center, you would expect to find hospital wards or labs filled with test tubes and microscopes. What you probably wouldn’t predict is to come face-to-face with vials full of blood-sucking bugs or willing volunteers offering themselves up to the tiny, many-legged vampires.

For Dr. Jesus Valenzuela, the mosquitos, ticks, sand flies that make a meal of us are less nightmare fuel than brain fuel, as he needs them for his studies on how the immune system responds to insect saliva. While seemingly a niche interest, Dr. Valenzuela’s research could eventually help save hundreds of thousands of lives each year. That’s because the world’s single deadliest animal is neither a venomous snake nor a large, aggressive predator with razor sharp teeth, but rather the humble mosquito, which spreads a whole alphabet of diseases from dengue fever and malaria to West Nile virus and Zika. And that’s not to mention tick-transmitted Lyme disease or the potentially deadly parasitic infection called leishmaniasis, which is spread by sand flies.

This video shows the parasites that cause leishmaniasis coming out of a sand fly's gut, where they undergo a key part of their life cycle before being transmitted to a human via the fly's bite.

“We’re not prepared for many of these insect-transmitted diseases,” Dr. Valenzuela says. “They can spread fast. West Nile virus is already found in many parts of the United States, and we’re seeing more and more cases of Lyme disease.”

Of course, an insect bite also exposes our skin to the insect’s saliva along with the disease-causing microbe. Vaccine research aimed at combating insect-transmitted diseases has focused almost exclusively on the latter, examining how a vaccinated immune system responds to a virus or parasite. However, Dr. Valenzuela thinks that scientists should be studying both of the factors responsible for these diseases.

Just like the weather determines if a winter coat will keep you comfortable or give you heat stroke, the conditions inside your body strongly influence how effective a vaccine-induced immune response will be. Importantly, those internal conditions might differ in people who have been bitten by a certain insect many times before compared to those who have never encountered it, yet that possibility is completely ignored in most vaccine research right now. Vaccine studies are mostly conducted in the U.S. and Europe, places where people aren’t pestered by disease-transmitting insects nearly as often as in the parts of the world where illnesses like malaria and leishmaniasis are ‘endemic’ — an unfortunate but established part of everyday life. As a result, even if clinical trials done in wealthy, Western countries show a vaccine is safe and effective, those findings might not hold up when the same vaccine is tested in other places.

Graduate student Vagner Dias Raimundo uses a magnetic rod to collect proteins in a flask that are attached to tiny magnetic beads, which he then places in the vial next to his left hand so the proteins can be analyzed.

“Most people in endemic areas are regularly exposed to insect bites,” Dr. Valenzuela explains. “When the mosquito bites them, if the person has been exposed before, they’re going to mount an immune response. What we never studied in those clinical trials is the effect of this immune landscape on a vaccine. We don’t know if it’s positive or negative, and we had never considered it.”

Solving that mystery is now a major component of Dr. Valenzuela’s research. In 2018, his team partnered with the lab of IRP senior clinician Matthew Memoli, M.D., an expert on clinical trials for flu vaccines, to recruit nearly 100 people who bravely volunteered to be bitten by disease-free sand flies or mosquitos. They found evidence that the volunteers’ skin developed a robust immune response as they were repeatedly bitten, an adaptation that might influence the effects of a subsequent vaccination. And if that study didn’t give you the heebie-jeebies, Dr. Valenzuela’s team is now analyzing the data from a similar one in which disease-free ticks fed on volunteers for days at a time.

The Valenzuela lab. From left to right: staff scientist Tiago Donatelli, Dr. Valenzuela, staff scientist Shaden Kamhawi, postdoctoral fellow Luana Rogerio, graduate student Luiza Felix, postdoctoral fellow Laura Willen (in the back), postdoctoral fellow Aline Da Silva Moreira, postbaccalaureate fellow Ronja Frigard, graduate student Vagner Dias Raimundo (in the back), postbaccalaureate fellow Kristina Tang, postdoctoral fellow Johannes Doehl (in the back), and assistant clinical investigator Joshua Lacsina

Once he is satisfied that he knows enough about human immune responses to uninfected insects, Dr. Valenzuela hopes to conduct trials in which he will vaccinate people against insect-transmitted illnesses such as dengue virus or leishmaniasis and then expose them to the bite of an insect carrying the disease.

“That saves lots of money and time compared to just waiting for natural exposure to happen, and you know whether your vaccine is going to work or not because you’re using the infected insect itself,” he says.

Of course, to conduct such studies, Dr. Valenzuela's lab needs a steady supply of infected insects. His team solved that problem by creating one of most effective facilities in the world for not only breeding large amounts of sand flies, mosquitos, and ticks, but also infecting them with all manner of viruses and parasites.

“Some other labs around the world do this, but not to the capacity we have,” he says.

IRP postdoctoral fellow Laura Willen examines a water-filled tray containing mosquito larvae.

Along with potentially helping to improve the effectiveness of vaccines, studying the saliva of illness-carrying insects has enabled Dr. Valenzuela’s lab to develop tests for exposure to sand flies and mosquitos. In the same way that antibody tests for COVID-19 can tell whether a person has previously contracted the virus, Dr. Valenzuela’s test detects antibodies in people’s blood that the body creates in response to certain substances in the insects’ saliva.

Such tests can point public health officials to the places where people are bitten most often by these disease-carrying pests, allowing for more efficient allocation of resources like vaccine doses and insecticides. This is particularly important in the parts of the world where these diseases are endemic, which tend to be less economically well-off and can’t afford to waste money vaccinating people or applying pesticides in places where people are not frequently bitten by sand flies or mosquitos. What’s more, Valenzuela’s lab is now collaborating with pharmaceutical company Pfizer to create a similar test for exposure to ticks, which are beginning to spread Lyme disease in more areas of the United States due to the expanding range of places where ticks can comfortably live.

This airlock — complete with bug zapper — separates the lab area from the insect breeding facility in order to prevent any of the insects from escaping.

The insect breeding facility relies on heaters and humidifiers like this one to keep the environment similar to the bugs' native climate.

"Right now, most studies check how many insects are present in an area by trapping them, but you don’t know if people were bitten or not until you do this antibody testing,” Dr. Valenzuela says, adding that ticks or sand flies may live somewhere but be confined to specific spots where people don’t go much, like certain patches of vegetation or rarely used hiking trails. Insects living near people also bite them less if the bugs are unable to enter homes. “That decreases the risk of disease transmission, but if you know in an area that people are being bitten, then the risk of contracting the disease increases significantly.”

One might not expect that studying insect spit could have so many important applications, but that’s exactly the sort of ‘basic’ research into the nitty-gritty details of biology that NIH’s Intramural Research Program is built to support. After spending the past three decades at NIH investigating the bugs that feed on us, Dr. Valenzuela is now in the midst of a smorgasbord of studies that could revolutionize how we stem the spread of the illnesses they transmit.

“As scientists, we really enjoy the moment of ‘wow’ when we discover something new and unique,” he says. “That’s food for us.”

Jesus Valenzuela, Ph.D., is a senior investigator in the Vector Molecular Biology Section at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

This page was last updated on Monday, March 3, 2025