Unexpected Leads to Curb Addiction

Lorenzo Leggio seizes new opportunities to develop treatments for substance use disorders.

The diabetes medication known as Ozempic has captured public attention since it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for weight management in 2021. It has garnered appeal as a wonder drug against obesity and provided much fodder for celebrity gossip, but accounts from people on the drug have piqued the interest of certain scientists and clinicians for different a reason.

Dr. Lorenzo Leggio

“People who got a prescription started saying ‘I got Ozempic for my diabetes, but I don't drink alcohol any longer or I don't feel I have the same compulsion to smoke like I used to,” says Dr. Lorenzo Leggio.

Dr. Leggio is a physician-scientist dedicated to the care of patients battling substance use disorders (SUDs), broadly defined as an inability to stop using mood-altering substances despite harmful consequences. He has spent the last two decades developing medications that could curb SUDs considering that the number of options available to the close to 50 million Americans living with this class of conditions is small. For example, only three medications — disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate — are approved by the FDA for alcohol use disorder (AUD). This pales in comparison with the number of options that exist for other common chronic diseases like Parkinson’s disease or hypertension.

The scarcity of options compels Dr. Leggio to investigate new leads, no matter how unexpected. If a medication like Ozempic, approved for a seemingly unrelated condition, happens to show promise treating SUDs, he argues the windfall is worth pursuing.

“Doctors who are treating addiction should have dozens of medications to choose from,” he says. “The mission I have as a physician-scientist in the IRP is to contribute to the menu of options.”

Few medications exists to help the nearly 50 million Americans who live with substance use disoders (SUDs), the most common of which is alcohol use disorder (AUD).

More options are necessary because the reasons that trap people in the vicious cycle of SUDs are varied. One person might be motivated to drink alcohol seeking a sensation of pleasure, for instance, whereas another person might find it relieves their stress. Consequently, any given medication might not work the same for everyone, or even for the same person over time, as the factors that drive their addiction can change.

“Just like treatments for hypertension or diabetes, treatment for a substance use disorder is for a lifetime,” Dr. Leggio explains. “You need to be engaged with a healthcare provider for the long-run.”

To expand treatment options, Dr. Leggio wants to broaden the view that the brain is the lone contributor to SUDs.

“Addiction is a brain disease and yet we fully recognize that the brain doesn't work in isolation,” he says. “If we study how our brain connects with the rest of the body, can we better understand addiction?”

More specifically, he wants to know how the nervous system and hormones circulating in our body interact to affect human psychology and behavior. It’s why he’s a proponent of studying compounds that mimic a specific hormone and appear to downshift addictive disorders, such as Ozempic’s active ingredient, semaglutide. Dr. Leggio recognizes their clinical potential because he has actualized it before, with other hormones like aldosterone.

Aldosterone helps control blood pressure and overall levels of fluid in the body and has been linked to cravings for alcohol in human studies. In a series of 2018 studies on rats, macaques, and humans, Dr. Leggio’s lab, together with several other investigators in the IRP and elsewhere, confirmed that higher levels of aldosterone are associated with higher levels of alcohol cravings and consumption. In the non-human primates, the team observed that individuals more prone to alcohol dependency had less cellular receptors that bind aldosterone in a part of the brain called the amygdala, which regulates reactions to heightened emotions and stress. Those receptors, known as mineralocorticoid receptors (MRs), were similarly less concentrated in the amygdalas of rats with higher levels of anxiety-like behaviors and compulsive-like drinking.

Although the data were consistent across species, it remained unclear whether lower MR levels led to more alcohol consumption or vice-versa. So, in 2022, Dr. Leggio and his collaborators in the IRP and at Yale University, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and Kaiser Permanente sought to untangle the chain of cause-and-effect by blocking MR activity with a drug called spironolactone. They found that dosing mice and rats with the drug reduced their interest in drinking alcohol.

What made spironolactone especially useful, though, was that it had already been prescribed in the clinic for decades to millions of patients for the treatment of high blood pressure and heart failure. Its long history meant the researchers could parse through large datasets of medical records to retroactively determine if spironolactone inadvertently altered patients’ drinking patterns. Sure enough, they found that patients who got a prescription for spironolactone drank less alcohol compared to those who didn't receive the drug, not only in one, but two separate databases. The results encouraged Dr. Leggio to initiate randomized clinical trials currently underway to determine the safety and efficacy of spironolactone as a treatment for alcohol use disorder.

Spironolactone, a heart medication that imitates the hormone aldosterone to help people get rid of excess fluid in their bodies and regulate high blood pressure, has inadvertently shown potential to curb alcohol consumption. Dr. Leggio and his team have investigated spironolactone for years and are moving into clinical trials to test its safety and efficacy as a treatment for alcohol use disorder.

“I love the story of spironolactone, because I think it's a good example of the highly translational and collaborative work you can do in the IRP,” says Dr. Leggio. “We took an initial observation in patients, then expanded this observation in animal models, generated a hypothesis of MR as a possible new target, selected a candidate molecule with spironolactone, tested it in animals, then did the big data science and now we’re going back to the clinic.”

Using the same approach, Dr. Leggio and his collaborators have also been investigating the addiction-reduction potential of semaglutide for years, well before Ozempic hit pharmacy shelves. As with spironolactone, research into semaglutide has been prompted by insights into neuroscience, animal studies and initial human studies that suggest a certain hormone receptor could make for a good drug target. In this case, semaglutide mimics the hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which is released in the gut during eating to signal a feeling of satiation, so it follows that it’s now implicated in moderating similar feelings of stress and reward involved in alcohol use.

Read more about Dr. Leggio’s research on semaglutide and its addiction-reduction potential in The NIH Catalyst.

Postbaccalaureate fellow Valerie Espinal Abreu (left) and postbaccalaureate fellow Rylie Conrad (right) simulate how the Dr. Leggio’s team uses a replica of a fully-stocked bar (all the bottles are filled with colored water) to test how potential medications affect alcohol consumption in a real-world setting.

“Momentum is high right now,” Dr. Leggio says. “Scientists in and out of NIH are conducting studies on semaglutide, but it’s important that we not put the cart before the horse. We don’t have enough evidence-based medicine yet to say, ‘yes, semaglutide works for patients with alcohol use disorder.’ It's going to take years to have answers."

Regardless of the outcome it’s important to temper expectations. Neither semaglutide, nor spironolactone, nor any other compound should be expected to cure SUDs altogether.

“I wish it was that easy, but it's not that easy,” Dr. Leggio says. “The medications are a piece of the puzzle of a more comprehensive care plan that patients should have with their medical providers,” including treatment methods like behavioral therapies that center around redirecting pervasive negative thinking to manage cravings.

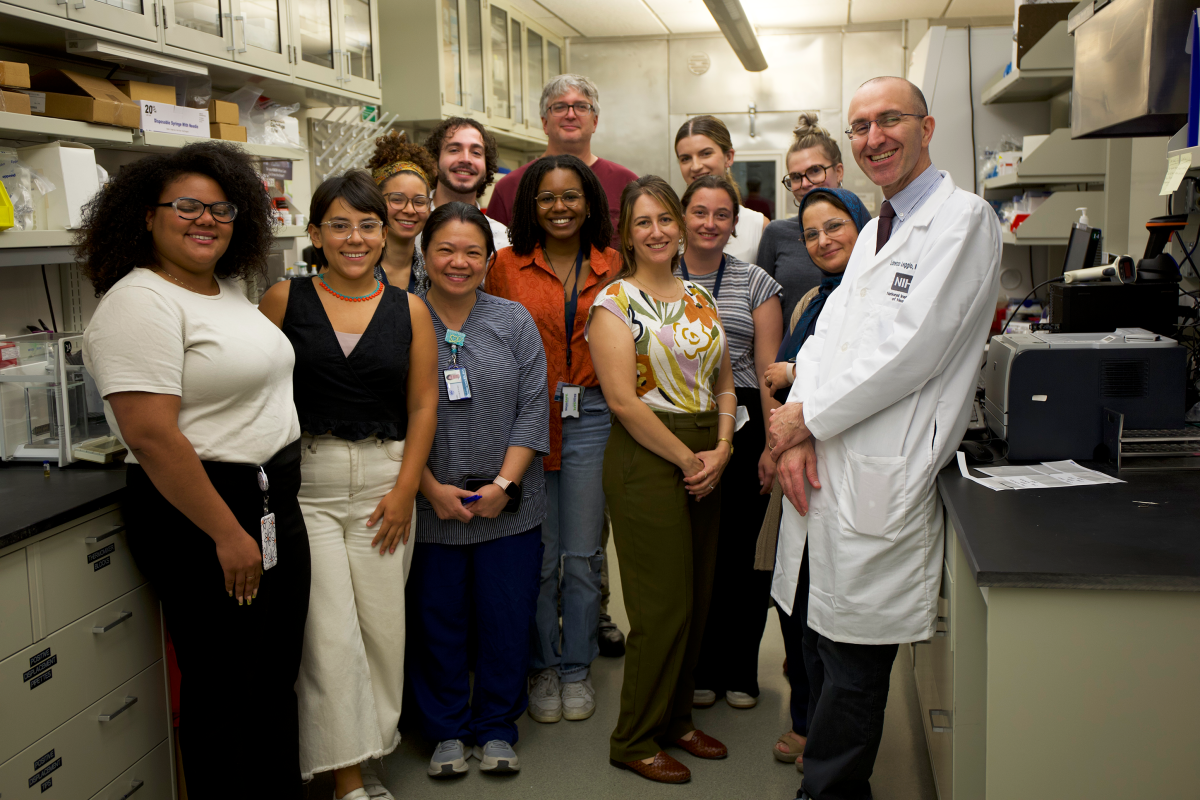

Members of Dr. Leggio’s Lab. From left to right: patient coordinator Ashley Batista, postbaccalaureate fellow Ana Sofia Rico Rozo, postbaccalaureate fellow Valerie Espinal Abreu, clinical research nurse Christine Lewis, postbaccalaureate fellow Ryan Zurick, postbaccalaureate fellow Bianca Beckwith, Translation Analytical Core manager Shelley Jackson, biological scientist Lindsay Kryszak, postbaccalaureate fellow Rylie Conrad, postbaccalaureate fellow Kelsey Isman, postbaccalaureate fellow Emily Herberholz, lab manager Azi Dejman, and Dr. Leggio.

The misconception that addiction comes from a lack of self-control can be particularly detrimental to those living with SUDs by fueling feelings of shame that preclude them from seeking help. However, shame from stigma is a symptom of society, not biology — one that Dr. Leggio’s work will help eradicate by proving that, like other mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, alcohol or substance use disorders are not a matter of weak will but a physical ailment in need of the right treatments.

Lorenzo Leggio, M.D., Ph.D., is the Clinical Director and Deputy Scientific Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), where he founded and heads the Translational Addiction Medicine Branch. He also founded and leads the Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology Section jointly held with NIDA and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

This page was last updated on Friday, December 13, 2024