Poster Session Showcases IRP Graduate Students

Event Includes In-Person Presentations for First Time Since 2020

Three years after COVID-19 dramatically changed the way scientists and many others work, much of life in the NIH IRP has begun to resemble the way things were in February of 2020. This includes the return of in-person scientific poster sessions like the one that took place on February 16 as part of the 19th annual NIH Graduate Student Research Symposium. Nearly 130 graduate students conducting their Ph.D. research in IRP labs as part of NIH’s Graduate Partnership Program presented their progress at that poster session and its virtual counterpart held February 15.

The two poster sessions made it clear that IRP graduate students are essential contributors to the life-changing discoveries made at NIH, from using geckos to learn about human eye diseases to investigating how the immune system combats infectious invaders to exploring ways to improve cancer treatment. Keep reading to learn about some of the bright scientists-in-training who showed off their work during the two-day event.

Ben Jung: Searching for Sex Differences in ADHD Genetics

“I don't remember a time when I wasn't interested in science,” says Ben Jung, who is working towards a Ph.D. in Neuroscience from Brown University by studying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the lab of IRP senior investigator Philip Shaw. Ph.D. The Shaw lab was a perfect fit for Ben, who initially became curious about the biological roots of ADHD while enduring his own struggles with the condition.

“When I went to college, I started struggling to keep up with the coursework, and eventually I was diagnosed with ADHD,” he recalls. “This came as a surprise to me, as I didn't fit my preconceived notions of what ADHD looks like, and so I found myself interested in learning more about the disorder.”

Alongside his colleagues in Dr. Shaw’s research group, Ben is exploring how certain types of genetic changes influence people’s risk for developing ADHD. Much of the research on ADHD and other conditions affecting the brain focuses on genetic changes to single letters in a person’s DNA sequence, known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). While this research has uncovered many SNPs that slightly increase a person’s odds of developing ADHD, other types of genetic variations have gotten comparatively less attention. That includes genetic changes called copy number variants (CNVs), which cause thousands or millions of base pairs to be duplicated or deleted from a person’s DNA.

“In most instances, a person has two copies of each gene, but a copy number variant can result in having extra copies of certain genes or missing copies of a gene,” Ben explains. “Having too many or too few copies of a gene can impact brain development, and so we want to investigate the role of these CNVs in ADHD.

So far, his investigation has shown that girls with large deletions in certain genes are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD. However, boys with such deletions are not at increased risk for ADHD, and CNV duplications don’t appear to increase the risk for the condition in either boys or girls.

“This is interesting because ADHD prevalence differs by sex — females are less likely to have the disorder in childhood compared to males,” Ben says. “Differences in the contribution of genetic risk factors for ADHD may contribute to differences in ADHD prevalence between males and females.”

“Understanding the genetic risk factors behind neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD can help us to better understand the pathways and mechanisms by which these disorders arise,” he adds.

As Ben continues to study how genes contribute to ADHD, he’ll have the help of a large and supportive collection of fellow IRP graduate students and more senior researchers, a community that he says is his favorite part of working at NIH. While he had several years of research experience under his belt when he joined Dr. Shaw’s team, including a two-year stint as a postbaccalaureate IRTA fellow in a different IRP lab, Ben is quick to admit that he needed the support of his peers to get up and running with his Ph.D. research.

“Being a graduate student at the NIH has been an incredibly rewarding experience, albeit with many surprises along the way,” he says. “It was my first time working in a genetics-focused and clinically-oriented lab, so there was a lot to learn. Luckily, everyone in my lab and the NIH community at large is supportive and helped to make a productive learning environment. I always feel like there's someone knowledgeable right around the corner that I can ask for help if I run into an issue with my research.”

Fun fact: In addition to his scientific ambitions, Ben hopes to one day visit every National Park in the United States.

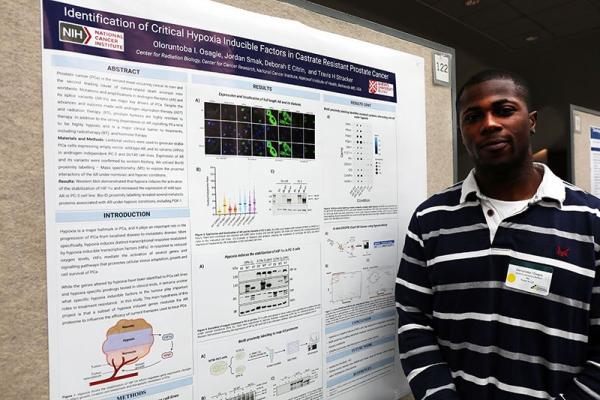

Toba Osagie: Curtailing Cancer’s Resistance to Therapy

The IRP’s cadre of graduate students includes numerous trainees from abroad. Toba hails from London in the United Kingdom and is enrolled in a doctoral degree program in Precision Medicine at Queen’s University in Canada. He has been fascinated by science since early childhood, which he attributes to the influence of his uncle, a physician.

“Witnessing his selfless dedication to helping others in a medical environment has always been a great source of inspiration for me,” Toba says.

When it came time to select a lab for his doctoral research, Toba chose to work in the Radiation Oncology Branch at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under the tutelage of IRP senior investigator Deborah Citrin, M.D., and IRP investigator Travis Stracker, Ph.D. With their help, Toba is investigating how low levels of oxygen in prostate cancer tumors, known as ‘hypoxia,’ allow the disease to resist radiation and chemotherapy treatments. The area immediately surrounding prostate tumors — its ‘microenvironment’ — often has low oxygen levels, and in addition to making the disease harder to treat, this characteristic helps the tumor grow and spread to other parts of the body.

“By gaining a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the hypoxia-induced alterations in prostate cancer cells, we can potentially discover novel therapeutic approaches that specifically target the hypoxic tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer,” Toba explains. “By identifying modulators of hypoxia sensitivity, we can improve current therapies and ultimately improve patient outcomes.”

Working towards improving prostate cancer treatment under the mentorship of experienced researchers like Dr. Citrin and Dr. Stracker has helped Toba hone his passion for ‘translational’ research with clear medical applications. At the same time, his work at NIH enables him to contribute to the fight against a disease that threatens the lives of many people like himself, since roughly one in six Black men will develop prostate cancer at some point in their lives. However, the IRP also provides Toba with many perks that require stepping away from his lab experiments.

“Since coming to the NIH, I have had the privilege of participating in numerous courses and training programs that were previously unavailable to me,” he says. “However, in addition to these opportunities, my favorite aspect of being at the NIH is the chance to meet and interact with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds.”

Fun fact: When he’s not fussing over test tubes or peering into a microscope, Toba enjoys playing tennis and soccer (which he of course calls “football”). He also taught himself to play the guitar a few years ago and says the instrument has now “become a significant part of my life and a cherished hobby.”

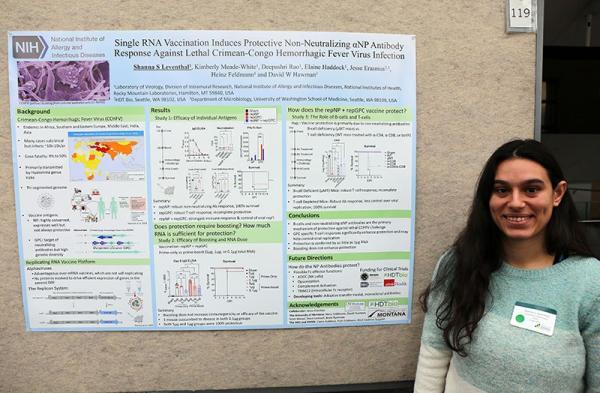

Shanna Leventhal: Targeting a Tricky Tick-Borne Illness

There must be something special about working in an IRP lab to get a Miami native like Shanna to move all the way to Hamilton, Montana. For Shanna, the main motivator was the unique opportunity to work in a bio-safety level 4 (BSL4) lab at NIH’s Rocky Mountain Labs campus in Hamilton. After all, Shanna had been interested in the very tiny organisms that infect humans since middle school.

“I found it fascinating and exciting to learn how microscopic processes could affect the overall health of the human body,” she says. “This intrigue led me to major in Molecular and Cellular Biology in college, where I began to learn the many ways viruses interfere with the cell to cause disease. I knew that was what I’d like to study in the future.”

Shanna has fulfilled that goal by enrolling in a Ph.D. program at the University of Montana and joining the lab of IRP senior investigator Heinz Feldmann, M.D., Ph.D., where she is specifically focused on the Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus (CCHFV), a deadly disease spread by ticks throughout Asia, Africa, and Europe. According to the World Health Organization, nearly a third of people who catch the illness die, and there is no approved vaccine or therapy for it. In part, this is because scientists don’t yet understand how CCHFV causes disease or how the body’s immune system fights it off.

To answer those questions, Shanna and her colleagues in Dr. Feldmann’s lab have developed a strain of CCHFV that can infect mice. That form of the virus has five genetic differences from typical CCHFV, and Shanna is trying to figure out which of those mutations allows the virus to evade the animal’s immune system as well as how the responsible mutations confer that ability, which could provide hints as to how the virus dodges immune responses in humans. Meanwhile, her lab has developed a vaccine for the virus that will soon begin testing in clinical trials to assess its safety and effectiveness. Shanna and her labmates are currently working to determine which specific immune cells combat CCHFV after someone receives the vaccine.

“This research has the potential to directly impact those at risk of CCHFV infection and disease, especially since our recent vaccine has received funding to enter clinical trials,” Shanna says. “However, those who are unable to receive a vaccination and become infected still need therapeutics. My research on how CCHFV causes disease will help inform the development of those therapeutics and help ameliorate major symptoms in CCHFV patients.”

The vast mountains and cruel winters of Montana might be a far cry from sunny and bustling Miami, but Shanna says the transition was well worth it. She has grown to love her new surroundings and learned a great deal about life as a scientist.

“I’m incredibly grateful to have the opportunity to do my graduate research at the Rocky Mountain Labs,” Shanna says. “Not only is Hamilton a beautiful place to live but, also, I’ve found my lab to be extremely supportive and encouraging. On top of this, I love my research topic and am continually excited to uncover the intricacies of CCHFV. Having a project that excites me and amazing people to work with makes it easy to show up to work every day.”

Fun fact: When Shanna moved to Hamilton, she began learning Brazilian jiu-jitsu. She is now a blue belt in the martial art, the next ranking up from the beginner-level white belt.

Andrew Wegerski: Gaining Vision Insights From Geckos

Andrew has had animals on the brain since a very young age. Growing up, he frequently visited zoos and aquariums, where he was “fascinated by the sheer variety of life,” he says. He eventually began volunteering at his local aquarium, which just so happened to be the well-known Baltimore Aquarium. He also raised exotic pets of his own, including octopuses, pythons, and a species of lizard call an Argentine tegu, which can grow to more than four feet in length.

With all this experience, he was just the man for the job when NIH’s National Eye Institute (NEI) sought someone to care for the zebrafish and geckos used in its research. After starting that position in 2016, Andrew began to realize that these animals were fascinating not only in their own right, but also for the ways they could be used to help people.

“Working with researchers passionate about genetics and vision science gave me an appreciation for this other field outside of my realm of knowledge,” he says.

Andrew’s presentation at the Symposium’s virtual poster session detailed his research in the NEI lab of IRP Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Robert Hufnagel, M.D., Ph.D., where Andrew is studying geckos in order to figure out how genes control the formation of the eye’s fovea, which is critical for high-acuity, color vision. Learning more about this part of the eye could lead to new treatments for vision-destroying diseases like macular degeneration. A species called the day gecko is uniquely suited to deliver those insights because they have a fovea, unlike nocturnal gecko species and the mice and rats that are so abundant in scientific research.

“When the fovea fails to develop properly or degenerates, as in the case of macular degeneration, it leads to significant vision loss,” Andrew explains. “Many commonly used lab animals lack a fovea, which makes it difficult to study. Because of this, much about foveal development is unknown.”

Of course, Andrew is learning not just from his reptilian research subjects, but also from his human colleagues in Dr. Hufnagel’s lab. With their help, he has gained invaluable new skills that will be critical to his Ph.D. research and his scientific future.

“I’m constantly learning new techniques to use and have an abundance of support from experts in the field,” Andrew says. “I’m being trained using cutting-edge technology and am fortunate to have a great lab to work in. My favorite part is that I’m able to tailor the techniques I’m learning to match my long-term career goals.”

Fun fact: At the Baltimore Aquarium, Andrew was responsible for training giant Pacific octopuses. He particularly enjoyed teaching them to voluntarily climb into a basket so they could be weighed more easily.

Brittany Brooks: Studying How Smell-Sensing Neurons Regenerate

Unlike many of her peers who worked as postbaccalaureate fellows or summer interns in NIH labs before returning to the IRP as graduate students, Brittany was a complete newbie to NIH when she joined the lab of IRP senior investigator John Ngai, Ph.D. However, despite never having worked in the IRP before, NIH had had a profound influence on her life. During high school and summer breaks as an undergraduate, Brittany participated in an NIH-funded program called Short-Term Research Experience Program to Unlock Potential (STEP-UP) that enabled her to accrue a large amount of experience in the lab even before she started her Ph.D. program at Howard University in Washington, D.C.

“That introduced me to the joys of research science at a very formative age,” she says. “Participating in the STEP-UP program is where I initially got the spark to become a scientist.”

After participating in STEP-UP, Brittany spent two years conducting neuroscience research at the Marine Biology Institute in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, an experience that instilled a passion for examining the intricacies of the nervous system. She is now aiming that interest at a part of the body called the olfactory epithelium, which harbors the neurons responsible for our sense of smell. It is also one of the only parts of the adult nervous system that continuously regenerates itself, thanks largely to a biological system called the Wnt signaling pathway.

By examining the activity of a variety of genes in olfactory epithelium neurons, Brittany hopes to improve our understanding of how Wnt signaling promotes regeneration when those nerve cells are damaged. What she and her colleagues learn could help lead to treatments for people whose sense of smell has been degraded by chemotherapy or radiation treatment for cancer or long-COVID, which often causes lasting problems with patients’ sense of smell.

Despite being new to life at NIH, Brittany settled in quickly thanks to the support of her IRP colleagues. In many ways, she says, working at NIH reminds her of her two years at Woods Hole, and those similarities helped her become comfortable here in short order.

“I had a magical summer in Woods Hole at the Marine Biology Laboratory because I was with amazing young scientists that were eager to learn, and working at NIH is the same, just on a larger scale,” she explains. “I work alongside outstanding scientists who are willing to provide a helping hand, and I have had the opportunity to be exposed to so many different resources that have contributed to my drive to be a scientist. It’s a joy coming into work everyday.”

Fun fact: Brittany is a U.S. military veteran — she served as a hospital corpsman in the U.S. Navy for four years. In her spare time, she loves to snowboard, play guitar, and visit Washington, D.C.’s many museums.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023