Global Scientists Come Together at the National Institutes of Health

Individuals From Around the World Drive IRP Breakthroughs

Come to NIH and you’ll hear many accents. Scientists from around the world have always contributed significantly to the NIH mission. The resulting diversity of backgrounds and perspectives makes the NIH Intramural Research Program an extremely stimulating and productive environment. Read on to learn about some of the many scientists of the past and present who brought their talents from abroad to one of the world’s leading institutions for biomedical research.

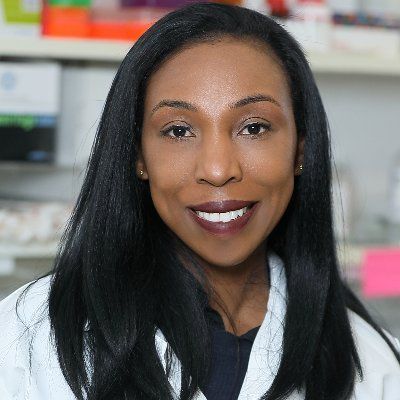

Dr. Kandice Tanner left Trinidad and Tobago, where she had been one of few girls at a boy’s school, to attend South Carolina State University, where she earned double degrees in electrical engineering and physics. In 2012, she came to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) through the Stadtman Tenure-Track Investigators Program to start a research program that combines her knowledge of physics with molecular and cell biology to study how cancer spreads. Specifically, her lab investigates how the conditions around a tumor, known as its microenvironment, affect its ability to move from one part of the body to another. After spending eight years as a Stadtman Investigator and earning numerous awards, including a 2013 NCI Director’s Intramural Innovation Award and the 2015 NCI Leading Diversity Award, Dr. Tanner was granted tenure last year and is now a senior investigator at NCI.

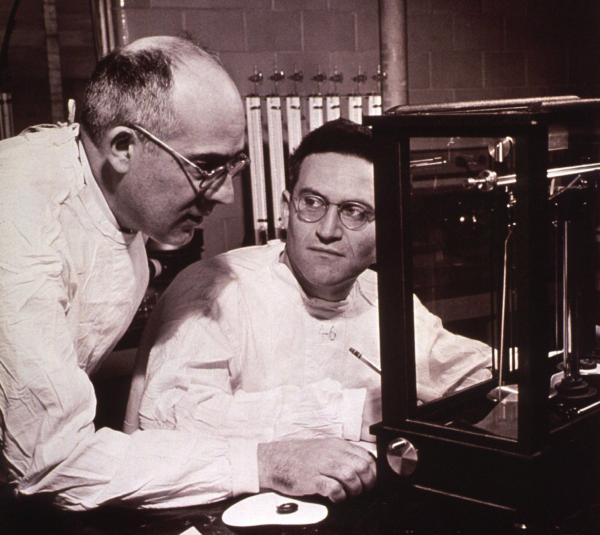

The Nazis dismissed Dr. Theodor von Brand from his post at Hamburg’s Institute for Tropical and Parasitic Diseases in 1933 — Dr. von Brand had not hidden his anti-Nazi views. In 1935, Dr. von Brand immigrated with his young family to the United States, and in 1947, he became the chief of the Section of Physiology in NIH’s Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, part of the NIH division that would eventually become the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). There, he pioneered the use of physiological and biochemical approaches to explore how parasites interact with their hosts and with drugs meant to kill them, instead of just classifying them and describing their life cycles. His six textbooks are classic studies of the parasitic diseases which affect millions of people around the world. In 1978, he was posthumously honored with the Robert Koch Medal. In this 1951 photo, Dr. von Brand (left) and Dr. Benjamin Mehlman prepare snails that carry the agent of schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever, for metabolic studies.

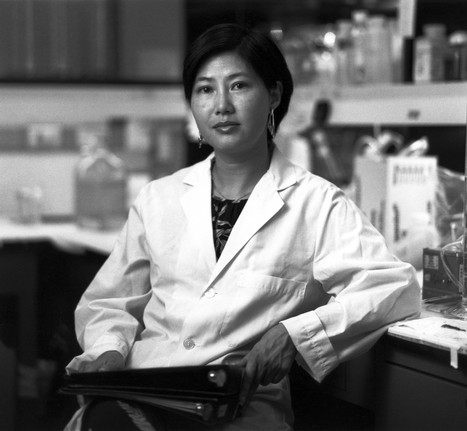

Dr. Flossie Wong-Staal helped identify HIV as the cause of AIDS, was the first to clone HIV for study, and created the first genetic map of HIV, which enabled the development of AIDS tests. She was born in mainland China, but her family moved to Hong Kong after the Communist takeover. Thinking that the West Coast of the United States would feel familiar from television and movies, Dr. Wong-Staal went to UCLA, receiving her Ph.D. in molecular biology in 1972. In 1973, she joined NIH’s National Cancer Institute (NCI), and her pioneering research there on HIV and AIDS ultimately led to her becoming the most-cited female scientist of the 1980s, according to an October 1990 article in The Scientist. In 1990, she returned to California as the Florence Seeley Riford Chair for AIDS Research at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Wong-Staal was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 1994 and the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2019.

If not for losing a coin toss, Dr. Wilhelm (Willy) Burgdorfer may never have come to the United States. He was born and educated in Basel, Switzerland, and as a college student, he investigated Q Fever outbreaks there. When Dr. Ralph Parker visited from NIH’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML), he told Dr. Burgdorfer’s professor that RML had a position for someone to study tick diseases. Dr. Burgdorfer and a fellow student flipped a coin, agreeing that the winner would go to Sardinia to study mosquitoes. Dr. Burgdorfer lost the coin flip and joined RML in 1952. He ultimately decided to stay there and became a medical entomologist. He is best known for discovering the bacterial pathogen that causes Lyme disease, a spirochete named Borrelia burgdorferi, in his honor.

Having spent most of her scientific career at NIH, Dr. Patricia Becerra has sampled the breadth of what the Intramural Research Program has to offer. Dr. Becerra was born in Lima, Peru, and completed her undergraduate studies there at Cayetano Heredia University before heading to Spain’s University of Navarra, where she received her Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1979. At that point, the reputation of NIH’s postdoctoral training program spurred her to come to the United States to work in the NCI lab of Dr. Samuel H. Wilson, where she studied enzymes that synthesize and break apart DNA molecules. Next, she went to NIAID to perform molecular virology research on the adeno-associated virus (AAV) under Dr. James A. Rose. She then returned to Dr. Wilson’s lab to investigate the structure and function of HIV reverse transcriptase, a molecule that the virus uses to turn its RNA genome into double-stranded DNA, a necessary step for it to infect cells. In 1991, she moved to NIH’s National Eye Institute (NEI) as a Visiting Scientist, and since 2003 she has led NEI’s Section on Protein Structure and Function, which focuses on how the structure of proteins found in the eye’s retina influence their functions. Her research group’s ultimate goal is to develop new treatments for diseases that damage or kill cells in the retina and lead to blindness.

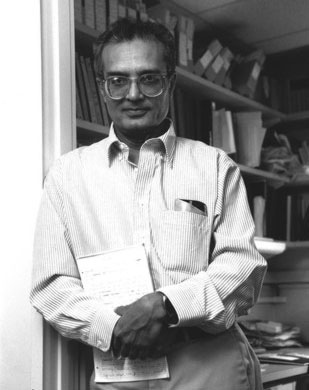

Dr. Sankar Adhya loved molecular genetics so much that he left India for graduate school in the United States, as India did not have training in that area. His passion also led to a job at the NCI’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology in 1971. There, he researches how DNA transcription is modulated and regulated by repressors, activators, terminators, and antiterminators. Dr. Adhya was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1994, a fellow of the Indian National Science Academy in 1995, a fellow of the Indian National Science Academy in 1992, and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2009.

“Spying” was how Dr. Claude Lenfant described his trip to the United States in the late 1950s, when he came from a French hospital to see how the Americans did cardiovascular surgery. Born and educated in France, he was an Assistant Professor of Physiology at the Université de Lille until he moved to the University of Washington in Seattle in 1966. Dr. Lenfant was invited to NIH to become the Associate Director of Lung Programs at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in 1972. He later became NHLBI’s longest-serving director, leading it from 1982 to 2003. Over the course of his career at NIH, Dr. Lenfant designed and implemented major clinical trials, launched initiatives such as the Programs on Genomic Applications, and oversaw public health initiatives such as the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program.

One of NIH’s newest investigators born outside our nation’s borders is Dr. Mario Penzo, who leads the Unit on the Neurobiology of Affective Memory at NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Dr. Penzo was born in the Dominican Republic and moved to Puerto Rico as a teenager. After completing his undergraduate studies in biology at the University of Puerto Rico, he came to the United States, ultimately earning his Ph.D. from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, where he studied mechanisms by which experience might influence the connections between neurons in the brains of birds. After a stint at New York’s Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory studying the neurobiological basis of fear-related memories, he came to NIH, where he continues to investigate emotion-related systems in the brain. In this photo, Dr. Penzo (right) reviews experimental results with Dr. Yan Leng, his staff scientist and lab manager. You can learn more about his work in this NIH Research in Action story.

From graduate students and postdoctoral fellows all the way up to senior investigators, NIH is commited to recruiting a diverse workforce. Science truly thrives when individuals with differing backgrounds work together towards a common goal, which is why NIH welcomes scientists from all over the world.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023