Symposium Spotlights Promising Female Scientists

Annual Event Recognizes Three Young Researchers’ Scientific Accomplishments

For decades, NIH has been working to solve the problems that have long stymied the careers of many young women interested in becoming scientists. As that essential effort continues, it’s important to shine a spotlight on some of the talented female researchers who are contributing to our knowledge of human health and biology right now.

One way the IRP does that is through the annual NIH Women Scientists Advisors (WSA) Scholar Award Symposium, which each year gives three early-career female scientists working in NIH labs the opportunity to present their work to the entire IRP community. At this year’s symposium, which took place April 29, the most recent group to be named WSA Scholars by NIH’s Women Scientists Advisors committee discussed their efforts to probe pollution’s impact on health, improve immunotherapy for cancer, and examine how screen time affects kids. Read on to learn more about their award-winning research.

Jennifer Zink: Scrutinizing Screens’ Effects on Kids’ Health

Over the past decade, both adults and children have begun spending more and more time looking at screens, whether laptops, cell phones, or televisions. That trend has become a cause for concern for many public health researchers, including Jennifer, who much prefers to be physically active rather than sit in front of her computer. In fact, her entire scientific career traces back to her interest in physical activity, as it started with a job as a researcher studying the topic after she finished her undergraduate studies.

“Through that, I learned I love research, but it really started with my interest in physical activity and then went from there,” she recalls.

Now, she is working with David Berrigan, Ph.D., M.P.H., at NIH’s Health Behaviors Research Branch to investigate how the type and amount of screen use kids engage in affects their risk of obesity and mental health problems like anxiety and depression. Using publicly available data about children from across the U.S., she has found that the link between screen time and health is more complicated than many might think. According to her analyses, while more time spent looking at screens increases risk for anxiety and depression among girls, it does not appear to have the same effects in boys. What’s more, certain types of activities that rely on screens have different effects on the risk of weight-related health problems. For example, it appears that the more boys use social media, the more likely they are to have higher body weights, but this relationship does not exist for girls. On the other hand, more time spent streaming videos online increases obesity risk for both boys and girls.

“All of this tells me that a behavior like screen time is very nuanced and complicated,” Jennifer says. “I think it’s really interesting because the behavior itself is changing as we see technology changing.”

Jennifer’s research suggests that different types of screen use have different influences on boys’ and girls’ health.

“Understanding whether and how screen time relates to long-term health outcomes is important and useful because we know that screen time and technology are not going anywhere, and I hope that my research can contribute to our understanding of how to use it in a healthy way,” she adds. “People are going to use screens, but if we can better understand how to do it in a healthy way where perhaps it’s not having such severe mental health- or weight-related implications, I feel like my research would be accomplishing my larger goal.”

For Jennifer, the specific focus of NIH’s efforts makes achieving that goal much easier, as she is surrounded by many colleagues that share her interest in improving the health of all Americans.

“I really love that the research I do at NIH is at a population level,” she says. “It makes me feel like it can more directly inform public health compared to doing research in other settings. I also really like that the goal of NIH is to improve the health and well-being of the entire U.S. population, and I really like that my research is contributing to that goal.”

Fun fact: Jennifer has had her dog Callie, a mix of a maltese and a poodle called a ‘maltipoo,’ since her first semester of graduate school nine years ago. “She has her Ph.D. also,” Jennifer says.

Jennifer Ish: Shining a Light Into the Smog of Industrial Pollution

Recent years have seen wildfires more and more frequently fill the air in many parts of the country with potentially dangerous levels of smoke. Much of the air pollution we breathe in, though, is man-made, and that exposure often occurs over much longer periods of time than pollution due to a natural disaster. Equipped with a graduate degree in epidemiology and a strong interest in how the environment affects health, Jennifer has the know-how and passion needed to investigate the often-complicated relationship between contaminated air and disease.

“My experiences during my undergraduate education — from coursework in both biology and sociology to a study abroad program focused on global health — solidified my interest in pursuing science and public health research,” she recalls. “I have always been particularly interested in environmental health and women’s health, and joining the lab I’m currently working in provided the opportunity to continue working in these topic areas.”

That lab is run by IRP Stadtman Investigator Alexandra White, Ph.D., and together Jennifer and Dr. White have been probing how chemicals released into the air by industrial facilities influence the risk of breast cancer in people living nearby. Until recently, most research examining the link between air pollution and cancer has focused on lung cancer, so Jennifer’s work is helping to fill in an important gap. She is also building on past work by focusing not only on individual pollutants, but also on the mixtures of those pollutants that people are exposed to.

Unsurprisingly, looking at the health effects of many different combinations of air pollutants is a difficult endeavor, and some of Jennifer’s results are as mixed as the chemicals that float through our air. Overall, no clear link emerged between breast cancer risk and the mixture of pollutants that women in her analysis were exposed to over a 10-year period. However, certain, rare mixtures of industrial air pollutants did appear to boost the women’s risk of breast cancer, although the low numbers of women exposed to those mixtures makes Jennifer hesitant to draw strong conclusions about their health effects. Still, her efforts are laying the groundwork for further research that will provide important information about how the chemicals released into the air by factories and other industrial activity affect women’s health.

Industrial processes release many different chemicals into the air, making it difficult to sift through how each of them, and the various combinations, affect health.

“As an environmental epidemiologist, I investigate how the distribution of disease among populations is influenced by the environment in which we live, work and play,” she says. “Air pollution is ubiquitous and contains a number of potentially harmful compounds, so it’s important to understand the consequences of exposure for health.”

Fortunately, Jennifer’s experience so far at NIH not only allowed her to study a topic she has long been interested in, but has also helped to sharpen her scientific skills. With the guidance that Dr. White has provided and Jennifer’s growing expertise, she is well-poised to build on the studies she has done so far and reveal new insights into how the air we breathe affects our bodies.

“Working in my lab at NIH has been the best training experience of my scientific career,” she says. “I am grateful for the mentorship I’ve received as well as the community of fellows that help to make it not only an enriching environment to do research, but also an enjoyable place to work.”

Fun fact: Jennifer describes herself as “a sucker for a good pun,” adding, “They always hook my attention!”

Chaido Stathopoulou: Improving Cancer Immunotherapy

Few illnesses are feared as much as cancer. However, the same traits that make cancer so mysterious and often difficult to treat are what attracted Chaido to study it.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the complexity of living organisms, and I always wanted to understand them on a molecular level,” she says. “Cancer research appealed to me because cancer is one of the biggest challenges in medicine.”

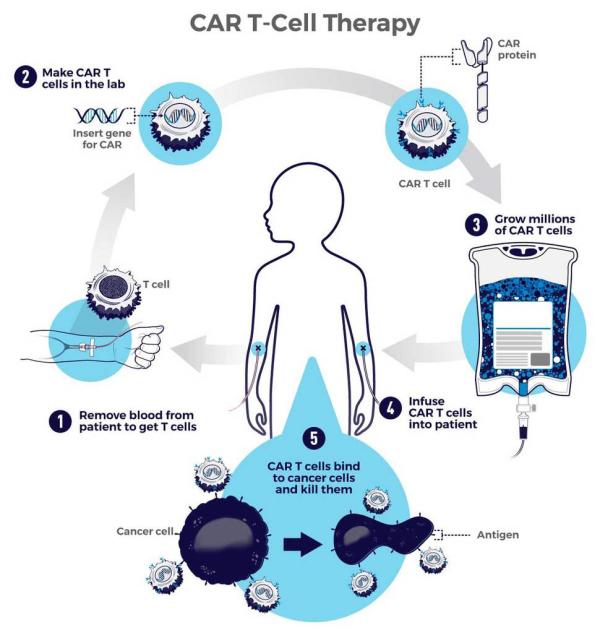

Originally from Greece, Chaido received her Ph.D. in the United Kingdom and then came to NIH to help IRP senior investigator Raffit Hassan, M.D., improve therapies that leverage the body’s own immune cells to combat cancer. She is specifically focusing on CAR-T cell therapy, which uses genetically engineered immune cells taken from a patients’ body to wage war on their illness.

The CAR-T cells Chaido is helping to develop are designed to preferentially attack cells that produce high levels of a protein called mesothelin, which is abundant in many forms of cancer. So far, her studies have found that her lab’s mesothelin-targeting CAR-T cells reduced how fast tumors grew in mouse models of a particular type of lung cancer, but did not cause the animals’ tumors to shrink. However, when she combined the CAR-T cells with another treatment that stops cancer cells from blocking attacks by the immune system, the mice survived longer than mice given just the CAR-T cell therapy. As a follow-up to those experiments, she is now looking at how CAR-T cell treatment alters tumors’ surroundings, with the hope that learning about those changes could be useful for improving the treatment.

This diagram shows the process by which CAR-T cells are created and used to treat a patient’s cancer.

“My research highlights molecular pathways that can be targeted to augment CAR-T cell therapy for solid tumors,” she explains.

With that goal in mind, Chaido looks forward to continuing her research at NIH, a place that she has found provides a wealth of resources to help her develop life-saving CAR-T cell treatments.

“My experience as a researcher at NIH has been very positive,” she says. “My favorite part is the collaborations with leaders in the field and access to cutting-edge technologies. Combined, these help me become a better scientist and accelerate my research, which ultimately aims to help patients.”

Fun fact: Unlike more than four-fifths of Americans, Chaido knows how to drive using a manual transmission, often referred to as ‘stick shift.’ “I purposefully chose to learn manual so that I can better understand how the car and the transmission work and be able to enjoy driving a wider variety of cars,” she says. “Also, you never know when the need may arise to drive a manual in the future, like in an emergency. I think it is an extra skill worth having.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Thursday, May 9, 2024