New Lasker Scholars Are Coming for Cancer

IRP Program Supports Cutting-Edge Cancer Research

The cumulative years of experience among the IRP’s large cadre of cancer researchers is truly astounding, with numerous scientists having spent half a century or more studying the disease at NIH. As incredibly valuable as their hard-earned wisdom is to finding new treatments for cancer, any scientific field also benefits tremendously from a constant influx of young talent. That’s where the IRP’s Lasker Clinical Research Scholars Program comes in.

The Lasker program identifies extremely promising early-career physician-scientists in a wide variety of fields and provides them with funding and resources to start their own independent labs at NIH. Over the past year, purely by coincidence, all of the Lasker Scholars selected happen to specialize in the study and treatment of cancer. Read on to learn more about the new ideas and bounding enthusiasm these fresh faces are bringing to NIH’s fight against the disease.

Rosa Nguyen: Investigating Immunotherapies for Cancer in Kids

Age may be the most important risk factor for developing cancer, as someone over the age of 60 is more than 40 times as likely to be diagnosed with the illness as someone below the age of 20. This makes it a particularly cruel twist of fate when cancer strikes a child. It’s no wonder, then, that Rosa Nguygen, M.D., Ph.D., chose to focus her career on combating cancers in children. However, she knew she wanted to work with kids long before she narrowed her focus to that particular illness.

“Growing up, I first became interested in medicine through my pediatrician,” Dr. Nguyen explains. “I remember sitting in the waiting area and seeing children of all different ages and with different problems and she could help them all — wow! Furthermore, she told me about her voyage from Haiti and how she overcame so many obstacles to study medicine and realize her dream of caring for children. She told me that my modest upbringing was not a barrier but encouraged me that I could go to university and contribute to society in a meaningful way as an adult if I worked hard and pursued my ambitions. These repeated conversations changed my self-belief and, ultimately, my life. Over time, I realized that I, too, wanted to be pediatrician and a role model to young children.”

Dr. Nguyen has a similarly vivid memory of the moment her career shifted to studying a form of cancer called neuroblastoma. This disease results in dense accumulations of cancerous cells that form ‘solid tumors’ atop the adrenal glands, in contrast to ‘liquid tumors’ like lymphoma and leukemia, two leading causes of pediatric cancer in which tumor cells originate in the blood, bone marrow, or lymph nodes. Dr. Nguyen’s first personal experience with neuroblastoma occurred during her first year of clinical fellowship, when she treated a young boy with a commonly used ‘immunotherapy’ designed to entice his immune system to attack his cancer.

“Once the infusion started, the little boy screamed at the top of his lungs due to pain, which is a common side effect of this treatment,” Dr. Nguyen recalls. “In the clinic, we pre-treat patients with analgesic medications and continue morphine throughout the infusion to mitigate the pain, but despite all these efforts, the little boy was in a lot of distress — and so was his father who held his hand at the bedside. I rapidly escalated his morphine infusion and, after some time, he and his dad were ok. However, I left the room mortified. I understood that we wanted to combat his cancer by any means possible, but it came at a significant cost.”

As Dr. Nguyen learned more about neuroblastoma, she discovered that grueling immunotherapy regimens like the one she administered to that boy don’t help roughly 40 percent of patients. She soon resolved to work on developing more effective immunotherapies that would not cause such severe side effects.

“This encounter coined how everything started, but countless clinical experiences since have shown me the dire need for better immunotherapies not only to treat neuroblastoma, but also other pediatric solid tumors,” she says.

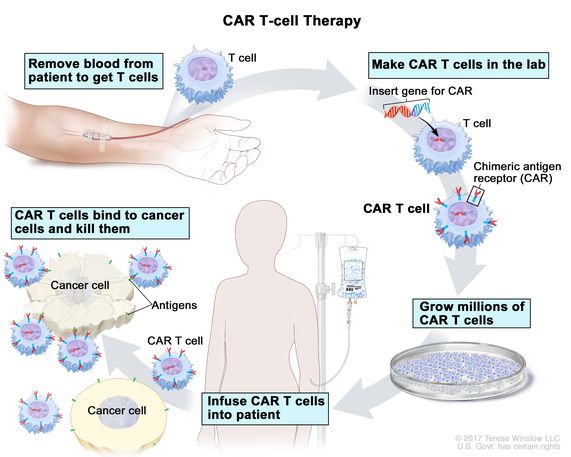

Since joining NIH, Dr. Nguyen has made significant strides towards that goal. In partnership with a large cadre of colleagues from across the IRP, she helped develop a new immunotherapy for neuroblastoma that utilizes so-called ‘CAR T cells,’ genetically manipulated immune cells that scientists have given the ability to recognize and attack a patient’s tumor. Now running her own fully-fledged lab for the first time as a Lasker Scholar, Dr. Nguyen hopes to refine this treatment and help guide it through clinical trials at NIH so that it can one day make its way into cancer clinics around the world.

This diagram shows how scientists create personalized CAR T cell therapies for cancer patients using immune cells taken from their own bodies.

“The Lasker Program has given rise to many brilliant physician-scientists in the past,” Dr. Nugyen says. “I wanted to be part of this wonderful program because I think it will maximize my chances of becoming a well-rounded researcher and developing an impactful research program within the intramural portion of the NIH that can hopefully benefit many patients in the future. I knew that the application process is highly competitive, so I was very excited and grateful when I found out that I was given the opportunity to continue my scientific and clinical career under the umbrella of the program.”

Being selected as a Lasker Scholar also ensures that Dr. Nguyen will be able to remain at NIH for at least the next five years and continue working with the brilliant scientists littered throughout the IRP.

“I like the environment and the science at the NIH,” she says. “We have an unparalleled, collaborative, supportive, and inclusive work environment here, with state-of-the-art resources to conduct true cutting-edge research. I love being part of this community and contributing with my science and medical care.”

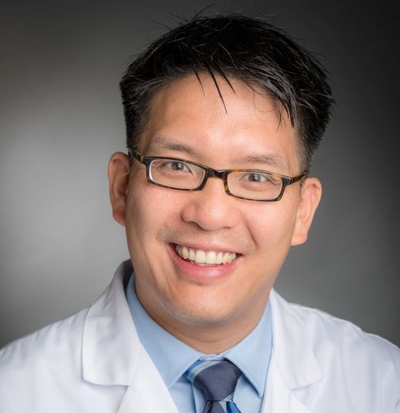

Samuel Ng: Searching for Lymphoma’s Weak Spots

For Samuel Ng, M.D., Ph.D., joining the IRP as a Lasker Scholar meant his career had come full-circle, since a summer internship at NIH during his junior year of college was what cemented his goal to make science and medicine a permanent part of his life.

“I didn’t have strong influences during my childhood day-to-day that encouraged me to become a physician,” Dr. Ng recalls. “I did kind of have this nebulous idea that I wanted to be a physician, and I did all the pre-med courses, but it wasn’t until that experience at NIH that I had a template for what being a physician-scientist could be.”

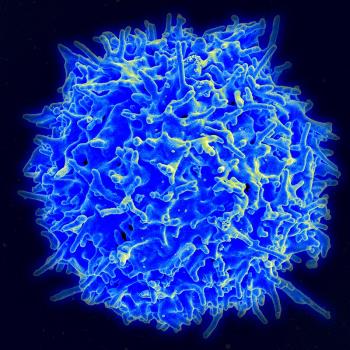

The immune cells that Dr. Ng studied at NIH that summer, called T cells, would become a common thread throughout his research career. Nowadays, Dr. Ng’s IRP lab studies what goes wrong in those cells to cause them to become cancerous. The specific class of cancers he studies, collectively known as T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, has generally proven more difficult to treat than non-Hodgkin lymphomas caused by problems with other immune cells called B cells. To help research on T-cell lymphomas catch up to its B cell cousins, Dr. Ng has been developing cell models of one type of T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma — specifically, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), which is one of the most common subtypes of the illness.

“When I started my postdoc, there weren’t very many cell lines for T-cell lymphomas, and particularly for AITL, none existed,” he explains. “We are using these cell lines to identify genetic vulnerabilities that could be exploited therapeutically.”

Dr. Ng’s research focuses on cancers caused my mutations in T cells like the one pictured here.

“There’s been so much development on the B cell side that I knew if I wanted to move the needle, T-cell lymphoma was a place where my work would really make a difference,” he adds.

Since Dr. Ng launched his lab at NIH last July, he has had more than a year to reap the benefits of working in the IRP, including generous resources that are “basically unparalleled for more junior investigators,” he says. The availability of those resources, in addition to the steady funding provided to IRP investigators, have given him the freedom to pursue research that he otherwise might not have, exploring questions that may or may not produce clear answers. With the freedom to test bold new theories in their experiments, Dr. Ng hopes he and his team can more quickly achieve life-saving breakthroughs for patients with T-cell lymphomas.

“That’s ultimately who we’re doing all of this for, and I’m just very humbled to have the privilege to participate and try to help them this way,” Dr. Ng says. “Being here and having the privilege and being entrusted with all these resources to make that sort of impact is something that is a responsibility, and I think that’s something I and every member of my lab embraces.”

Ramya Ramaswami: Improving Treatment For HIV Patients With Cancer

Our immune systems don’t just guard against invaders from outside the body, such as viruses and bacteria; they also protect us from internal threats like cancer. As a result, when HIV attacks the immune system, it makes the body more vulnerable to both infectious diseases and cancer. Some infectious diseases like the Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV) can even cause cancer themselves.

Ramya Ramaswami, M.B.B.S., M.P.H., has spent the past four years studying not only the cancer caused by KSHV, known as Kaposi sarcoma, but also other ailments that sometimes come along with it.

“KSHV can lead to a panoply of conditions that can emerge at the same time as Kaposi sarcoma, making people very unwell,” she explains. “Kaposi sarcoma is very distinct on the skin and many other conditions caused by KSHV are often missed. This can be a problem because the treatments may be different depending on the nature of KSHV-associated disorders.”

By better understanding these KSHV-associated diseases, Dr. Ramaswami hopes to provide physicians with better diagnostic tools “so that patients can receive timely and targeted treatment to improve their outcomes,” she says. And now that she has been selected as a Lasker Scholar, she plans to expand her research to exploring other virus-associated cancers aside from Kaposi sarcoma that disproportionately affect people living with HIV.

“This population is often excluded from cancer clinical trials and is often unable to benefit from cancer care advancements,” she says. “I wanted to help drive change for this population.”

That work requires Dr. Ramaswami to collaborate with experts in a range of fields, including fellow cancer physicians, virologists, and immunologists. Fortunately, that sort of teamwork and communication across disciplines is right up Dr. Ramaswami’s alley, and it’s made easier by the common goals that she and her collaborators share. In fact, those commonalities were one of the main reasons she was drawn to science in the first place.

“As a product of many cultures and born an Indian immigrant in Singapore, I was particularly drawn to medicine from a young age because medicine seemed universal,” she says. “Even with all the advances in medical science, ultimately it comes down to individuals: one who seeks help for their ailment and someone else with the knowledge and expertise to provide a meaningful remedy. That’s true wherever you are in the world and irrespective of the language you speak.”

Dr. Ramaswami’s opportunities to team up with fellow IRP scientists will only grow now that she has the backing of the Lasker Scholars Program. As it has over the past few years, the expertise and experience of her colleagues will continue to play a key role in her efforts to organize clinical trials testing new ways to treat life-threatening, HIV-associated cancers.

“As someone working on clinical trials for patients with cancer and HIV, my work is naturally collaborative” she says. “I love the interactions and the learning between scientists and clinicians from different disciplines. The ability to work through a problem together by applying our diverse perspectives and expertise is so unique to the NIH. It’s an exceptional environment.”

Conversations with colleagues aren’t the only way that Dr. Ramaswami thinks through problems, though. Having a creative outlet in painting and drawing helps her gain perspective on the challenges she and her patients face, not to mention the relief it provides from the high-intensity work of caring for the very ill.

A sample of Dr. Ramaswami’s artwork. She says that painting and drawing allow her to step back from her work and think creatively about the obstacles she encounters in her research and in the clinic.

“I think it’s important to find angles and avenues to cultivate creative approaches, and I find that art enables that,” she says.

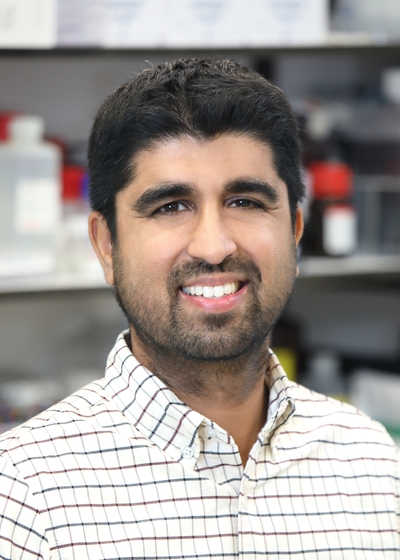

Nitin Roper: Looking Into Lung Cancer’s Response to Immunotherapy

As an avid skier and tennis player who commutes to and from work on his bike, Nitin Roper, M.D., M.Sc., knows well the tremendous power of the lungs. Once he catches his breath each morning, he picks up where he left off in his mission to improve treatment for lung cancer.

Dr. Roper is focused specifically on ‘small cell’ lung cancer, a type of tumor thought to arise from cells in the lungs known as ‘neuroendocrine’ cells, which secrete hormones into the blood in response to signals from the body’s nervous system. His day-to-day day life now is notably different from what he originally thought he would be doing when he arrived at NIH in 2015 as a medical oncology fellow with “little background in the lab, having spent the last many years in clinical training,” he recalls.

“I expected to do clinical research, but I soon realized that the most significant discoveries that could be made in cancer occur in the lab, and NIH has outstanding laboratories and translational research opportunities,” he explains.

Now with nearly eight years in the lab under his belt, Dr. Roper is rearing to utilize the resources provided by the IRP and the Lasker Scholars Program to change the way doctors treat neuroendocrine lung cancers, as well as neuroendocrine tumors that form in other parts of the body. His lab’s first step in that endeavor is identifying the molecular factors that predict how small cell lung cancer responds to immunotherapy. By doing so, his research may one day help make immunotherapies more effective and increase doctors’ ability to match patients to the right treatments.

“When immunotherapy became a major new treatment option for lung cancer, it was clear to me that this would be a critical area to work on,” Dr. Roper says.

“As a physician, I can think of no better outcome of an experiment than if it can ultimately apply to the clinic,” he continues. “If any of these new treatment approaches developed in my lab improve patients' lives, I would be satisfied that I picked the right career path.”

That path has been profoundly influenced by “many experienced and wise mentors here at the NIH,” he says, making it an easy choice to remain there when it came time to launch a lab of his own. Dr. Roper also believes that the IRP’s emphasis on high-risk, high-reward research makes it an ideal place to continue his career.

“NIH is a special place that allows investigators to pursue creative, bold, and risky ideas,” he says. “I want my lab to take those risks because, without doing that, we won’t be able to impact the lives of cancer patients in a meaningful way.”

Payal Khincha: Protecting Families With Elevated Cancer Risk

Sometimes careers are passed down through families just like genes are. This was certainly the case for Payal Khincha, M.B.B.S., M.S.H.S., who was inspired from an early age to become a doctor by her father, who works as a surgeon in India.

“His approach, bedside manner, and care to his patients really struck me, as did the total faith, respect, and trust his patients had in him to be taken care of well,” she recalls.

It was only later in life, though, that Dr. Khincha fell in love with research. In 2012, while doing a medical fellowship at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., she met IRP senior investigator Sharon Savage, M.D., who at the time was studying families with a much different inheritance than the one Dr. Khincha got from her father. Due to mutations in certain genes passed down through generations, people from certain families tend to develop cancer at much higher rates than the general population, and at much earlier ages. Dr. Savage specializes in studying those families, and Dr. Khincha decided to join her IRP research group to fulfill the research requirements of her fellowship.

“Little did I know I would completely love the work I did and the families I met and got to know so well,” Dr. Khincha says. “On completion of my fellowship, I grabbed the opportunity to stay on at the NIH to do full-time clinical research and the rest, as they say, is history!”

Dr. Khincha would eventually take over from Dr. Savage as the lead researcher on a long-term study of Li-Fraumeni Syndrome (LFS), a condition caused by mutations in the TP53 gene that dramatically increases the risk of developing multiple types of cancer. The cellular systems that suppress cancer in individuals with LFS are so thoroughly disrupted that it is not uncommon for people with the condition to get their first cancer diagnosis before the age of 35.

By examining the biological reasons why people with LFS are so vulnerable to cancer and developing improved methods of monitoring them for tumors, Dr. Khincha hopes she can help stop cancer from affecting their lives so significantly. For example, her research has revealed that scanning LFS patients’ entire bodies once per year with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is an effective way to detect cancer early in those individuals, thereby potentially making treatment more effective. Currently, she is developing a clinical trial that will examine whether the medication known as metformin, traditionally used to treat diabetes, can reduce the risk of developing cancer in adults with LFS.

“The impact of the research we do and the answers that we find are so important to the families who are affected by these disorders — for their daily lives, management of cancer risk, and overall well-being,” Dr. Khincha says. “It has given me immense professional satisfaction and reward to work with these individuals and families closely, as well as leverage the vast resources of the NIH in creating some of the largest cancer predisposition studies in the world.”

“LFS is among the most severe cancer predisposition syndromes, perhaps the most severe, with extremely high lifetime cancer risks starting from infancy, as well a very high risk of developing multiple different cancers as well,” she continues. “The need for science is so high, and every discovery is critical to their outcomes.”

Now as a Lasker Scholar, Dr. Khincha will continue working to learn more about LFS and other conditions that raise cancer risk. In addition, she emphasizes, her patients constantly teach her lessons that have little to do with the molecular and medical details of their genetic syndromes.

“From the families and studies I work with, I have learned about resilience, acceptance, grief, and the importance of a big-picture perspective on life and not worrying too much about the finicky details,” Dr. Khincha says. “I truly believe they have helped make me a better person, physician, and scientist.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024