Remembering Robert B. Nussenblatt, 1948–2016

Robert B. Nussenblatt, 1948–2016

Last month we lost a remarkable investigator, Robert Nussenblatt, M.D., M.P.H., chief of the Laboratory of Immunology at the National Eye Institute (NEI). Bob was a world-renowned expert in uveitis, an inflammatory eye disease and a leading cause of blindness in younger people. He was instrumental in establishing the pathology of and treatment for uveitis. Bob was diagnosed with a metastatic cancer just a few months ago. He remained characteristically optimistic even as his prognosis rapidly grew worse. He died on April 17, 2016, at age 67 with his family by his side. The NIH staff just devastated to hear the news of his death, because so few knew Bob was ill.

Bob arrived at the NIH IRP as a clinical associate in 1977. He became chief of the NEI Clinical Ophthalmic Immunology Section by 1981 and soon after founded the Laboratory of Immunology, which includes four sections related to immunology. He served as NEI scientific director through most of the 1990s and was a senior advisor to me, the Deputy Director for Intramural Research, since 2001. He was appointed by the NIH Director as an NIH Distinguished Investigator this year.

For nearly four decades, Bob was the embodiment of translational research, using knowledge gleaned from his passionate clinical practice to inform basic research and develop therapies to be tested back in the clinic. Among his work with the most clinical impact was his use of cyclosporine, an immunosuppressant drug often administered to prevent rejection in organ transplantation, to treat uveitis, the inflammation of the uvea and surrounding areas in the eye. Bob was the first to take the approach of using an immunosuppressant compound for uveitis, which many at the time thought was unlikely to be effective. Yet cyclosporine has become a standard treatment for uveitis, sparing many patients from the long-term use of steroids to control this condition.

In more recent work, Bob demonstrated the effectiveness of daclizumab, another immunosuppressive agent (developed by Thomas Waldmann of NIH), for the treatment of uveitis. His protocol for the use of daclizumab has subsequently been adapted for treatment of multiple sclerosis. I should note that Bob’s book Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice, now in its fourth edition, is considered the pre-eminent text in its field. Bob also made major contributions to the development of treatments for AIDS-related eye disease and, quite recently, the immunological aspects of age-related macular degeneration.

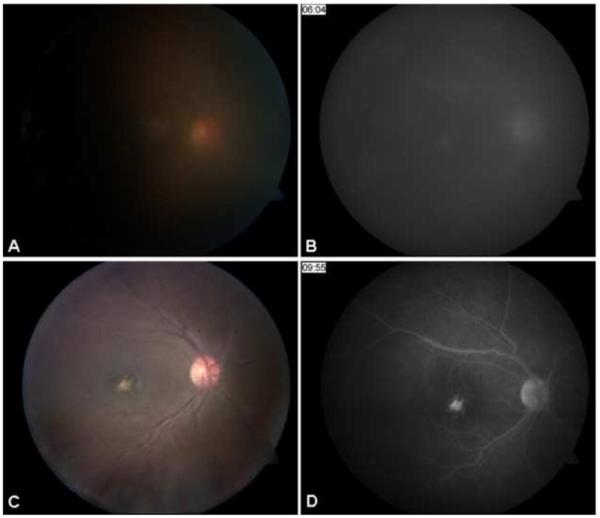

Treating uveitis with daclizumab: Fundus photo (A) and venous phase fluorescein angiogram (B) of a patient at baseline demonstrates 2+ vitreous haze and mild hyperfluorescence of optic nerve and fovea OD. Following administration of induction doses of high-dose daclizumab therapy and subcutaneous daclizumab every four weeks, fundus photograph (C) and venous phase angiogram (D) at final follow-up demonstrate resolution of vitreous haze, decreased optic nerve hyperfluorescence and staining of a macular scar. Source: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2742388/

Bob recognized the importance of team science and pursued it at an international scale. He led the UNITE consortium, which partners NEI with sites in the United Kingdom, South China, and Hong Kong in the study of ocular inflammatory diseases. In the NIH intramural program, Bob helped create and was the NIH clinical director for the Center for Human Immunology; was acting scientific director and clinical director for the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (now NCCIH) for several years; was director of the Office of Protocol Services at the NIH Clinical Center; and otherwise lent his talents to countless collaborations.

Bob helped me on many occasions deal with complex ethical issues related to conflict of interest, research on vulnerable subjects, and the ethics of clinical investigation. He was a nuanced and sophisticated historian and ethicist whose views were always practical and who balanced the important ethical benefits of research with protection of human subjects. Scores of trainees passed through Bob's lab and clinic, many of whom are now leaders in the broader field of ophthalmology. His past fellows and students have established an alumni organization that meets biannually, with the Nussenblatt Lecture delivered by an alumnus as a centerpiece of these meetings.

Rachel Caspi, an NEI senior investigator, described Bob as being deeply devoted to patient care and representing the finest in the NIH tradition of trying to understand the basic mechanisms of a disease in order to find a cure for it. So as one can imagine, Bob had numerous professional accolades that complement these personal remembrances. He received the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Life Achievement Honor Award in 2011. He was listed among the ‘Best Doctors in America’ and the ‘Top Ophthalmologists in the United States’ and held many visiting professorships. He was elected president of the Association for Research on Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO), the American Uveitis Society, the Federation of Clinical Immunology Societies, and the International Uveitis Study Group. He served on many editorial boards, including the American Journal of Ophthalmology, and he published more than 600 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters.

Beyond the science, Bob was well versed in culture and current events. He was fluent in French and spoke it at home. (His wife, Rosine, is from the French-speaking part of Switzerland.) He could also navigate in Russian and Hebrew and would entertain long conversations on topics such as religion, philosophy, geography, and world affairs. Nida Sen, an NEI staff clinician and long-time collaborator, described Bob as always being the optimist in the room. He was an extraordinary man with outstanding achievements in science yet had an unbelievable modesty and humility, making everyone around him feel welcomed, she said. Chi-Chao Chan, Bob's first fellow in 1982 and now a NEI Scientist Emerita, described him as a mentor and supporter for female scientists, in particular, and first and foremost a family man. He put his family first and inspired his lab members to put their families first, she said. He considered his lab to be his extended family.

Bob is survived by his wife Rosine and his children Veronique, Valerie, and Eric.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023