Exhausting Tumor Cells Makes Them More Vulnerable to Immunotherapy

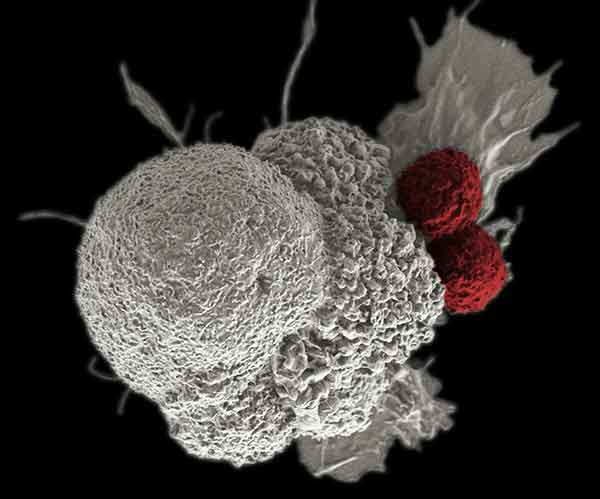

IRP investigators have found evidence that a compound called AZD1775 makes cancer cells (white) more vulnerable to attack by the body’s immune cells (red) by preventing the cancer from pausing its life cycle.

The constant combat between cancer and the body’s defenses can wear a tumor out. Unfortunately, cancer cells can pause their life cycle to repair themselves before re-entering the fray with renewed vigor. According to new IRP research, preventing cancer from taking a time-out can make it more susceptible to attack by the immune system.1

Techniques that use the body’s innate defenses to fight cancer are at the cutting edge of modern cancer therapy. Known as immunotherapies , these approaches spur immune system cells like T cells and natural killer cells to attack tumors. Those two cell types kill cancer cells using a molecule called granzyme B, which triggers several cellular processes that ultimately cause severe damage to the cancer cells’ DNA. If this damage is not repaired before a tumor cell undergoes the process of cellular division, called mitosis, the cell will self-destruct.

“If you push cells prematurely into mitosis, and there’s DNA damage that hasn’t been repaired, the DNA just starts to fall apart,” says IRP investigator Clint Allen, M.D., the study’s senior author.

However, cancer cells have long frustrated clinicians and researchers by temporarily halting their life cycles when attacked by the immune system, thereby buying time to repair DNA damage before dividing. Figuring out how to prevent this delayed mitosis is an active area of cancer research.

Dr. Allen found a clue in a recent University of Washington clinical trial that showed that giving cancer patients a compound called AZD1775, which inhibits a cellular enzyme called WEE1 kinase, made chemotherapy much more effective in some patients.2 Dr. Allen had seen this sort of pattern, in which a small subset of patients improve significantly after treatment while the rest fail to benefit, in trials he had run with immunotherapies, so the study made him wonder whether AZD1775 was helping the patients’ immune systems attack their tumors. A paper published two decades ago, showing that activating WEE1 kinase prevents granzyme B from killing cancer cells by pausing the cells’ life cycle prior to cell division,3 added to his suspicions.

“This idea that dysregulating the cellular life cycle can affect how well granzyme B kills tumor cells — we’re not the first to discover that, but it had been around for 25 years and nobody had taken it and ran with it,” Dr. Allen explains. “Seeing the dramatic responses in the patients at the University of Washington and finding this paper made the light bulb go off and made us think this is something we need to explore to see if it can be universally applied to immunotherapy.”

Dr. Allen’s team first showed that more mouse cancer cells died when they were put in a petri dish with mouse natural killer cells and AZD1775 than when the drug was absent. Similarly, a cellular immunotherapy created from human natural killer cells killed more human cancer cells in a petri dish when it was accompanied by AZD1775. Adding an FDA-approved cancer drug called Avelumab, which incites the immune system to attack cancer cells, further enhanced the combo’s cancer-fighting capabilities.

The researchers also found that mice with aggressive, malignant tumors survived longer when given a transfusion of mouse natural killer cells in combination with an injection of AZD1775, compared to mice given just the drug or the immune cells. Subsequent experiments revealed that this effect occurred because inhibiting WEE1 kinase with AZD1775 prevented the tumor cells from pausing their life cycles before replicating. Without this time out to manufacture and deploy additional compounds used to repair damaged DNA, the cells ended up exhausting the resources they needed to keep themselves going, like a marathoner whose legs give out after running too long without a break.

Dr. Allen’s lab now hopes to uncover why WEE1 kinase becomes active and pauses the cellular life cycle when immune cells attack cancer cells with granzyme B. Meanwhile, his group and others are planning clinical trials testing the combination of immunotherapy and AZD1775 in cancer patients. According to Dr. Allen, a soon-to-be-published study from his lab showed that AZD1775 also makes cancer cells more vulnerable to T-cell-based immunotherapies, suggesting that the drug could be a useful accompaniment to many, or potentially even all, immunotherapies.

“Whatever your immunotherapy approach is, the cancer cells are always going to have the same ways to resist being killed,” he says. “If you could make the cancer more sensitive to whatever immunotherapy you use, you could end up with something that’s broadly applicable.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Inhibition of WEE1 kinase and cell cycle checkpoint activation sensitizes head and neck cancers to natural killer cell therapies. Friedman J, Morisada M, Sun L, Moore EC, Padget M, Hodge JW, Schlom J, Gameiro SR, Allen CT. J Immunother Cancer. 2018 Jun 21;6(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0374-2.

[2] A Phase I Clinical Trial of AZD1775 in Combination with Neoadjuvant Weekly Docetaxel and Cisplatin before Definitive Therapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Méndez E, Rodriguez CP, Kao MC, Raju S, Diab A, Harbison RA, Konnick EQ, Mugundu GM, Santana-Davila R, Martins R, Futran ND, Chow LQM. Clin Cancer Res. 2018 Jun 15;24(12):2740-2748. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3796. Epub 2018 Mar 13.

[3] Rescue from Granzyme B-induced Apoptosis by Wee1 Kinase. Chen G, Shi L, Litchfield DW, Greenberg AH. J Exp Med. 1995 Jun 1;181(6):2295-300.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024