African Ancestry May Influence Immune Response to Prostate Cancer

IRP Study Could Help Explain Racial Disparities in Disease Outcomes

A new IRP study suggests ancestry-based differences in how the immune system works may be one reason why Black Americans are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as white Americans.

Even as advances in therapy are extending the lives of many cancer patients, there are still stark differences in how likely patients of different races and ethnicities are to die from the disease. A recent IRP study suggests that a weaker immune response against cancer could explain the worse clinical outcomes for Black men with prostate cancer, pointing to potential strategies that could help close this gap.1

In the United States, Black men are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer as white men.2 Socioeconomic and environmental factors like access to healthcare and stress play a large role in this disparity, but innate biological differences between men with African and European ancestry also likely contribute, just like they do for certain other illnesses, such as sickle cell disease. Differences in the immune system’s ability to ward off cancer have been an area of particular scientific interest.

“We know from papers that have been published that the immune system has evolved in different ways in different geographical areas,” explains IRP senior investigator Stefan Ambs, Ph.D., M.P.H., the new study’s senior author. “In the tropics, people get different infections than in the temperate zone, so the immune system has evolved in a way that increased the likelihood of survival in tropical areas. That is why there can be population differences in the immune system, and then the question becomes whether that is important in cancer.”

Certain genetic variants are more common in people whose ancestors hail from particular parts of the world, and these genetic differences can make some groups of people more prone to specific diseases.

In the new study, Dr. Ambs’ team worked with colleagues within and outside NIH to determine how the likelihood of dying from prostate cancer was related to the levels of 82 different molecules known to be involved in the immune system or the development of cancer. To do so, the researchers measured the levels of those 82 molecules in blood samples from nearly 3,000 men with and without prostate cancer from the United States and Ghana, a country in West Africa.

The scientists found that the levels of those molecules in the blood of participants without prostate cancer differed noticeably between European Americans, African Americans, and Ghanaians, with men in the latter two groups being more similar to one another on this measure than they were to the European men. In addition, when the researchers looked at 100 ancestry-related genetic variants to estimate the amount of West African ancestry in the American participants without prostate cancer, they found that levels of nearly 40 of the molecules were influenced by the amount of West African ancestry that the Americans had.

To examine how these differences might affect biological processes in the body, the researchers grouped the 82 molecules into six categories based on their functions. This approach revealed that levels of molecules related to a process called ‘chemotaxis,’ which helps cells move around, were higher in African American men without prostate cancer than in healthy European men. This increased mobility of cells could make prostate cancer more likely to spread to other parts of the body in African Americans, a process known as ‘metastasis’ that dramatically increases the likelihood a cancer will be lethal. What’s more, the levels of molecules related to suppressing the immune system’s response to a tumor were higher in cancer-free African American men than in cancer-free European men, while the levels of proteins that promote an immune response against cancer were lower.

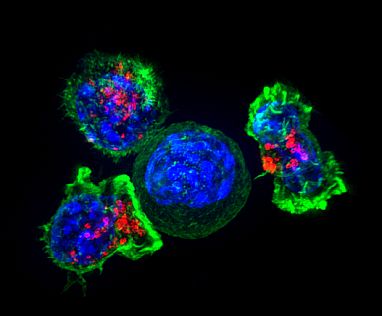

Image credit: Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz, and Gillian Griffiths

Immune cells known as ‘killer T cells’ surround a cancer cell. These T cells attach to and spread over their target, then use special chemicals (red) to destroy it.

“The immune system on one side fights invaders, but on the other side, when it over-reacts, you can get autoimmunity,” Dr. Ambs says. “That is the balance that the body always has to maintain. Perhaps some of the adaptations we see in West African people are part of maintaining this balance.”

The researchers next looked at how levels of the various molecules affected health outcomes. They found that prostate cancer patients who had higher amounts of molecules that suppress anti-tumor immune responses were significantly more likely to see their cancer spread to other parts of the body, and also more likely to die, than those with lower levels of those proteins. However, levels of those molecules did not appear to influence the risk of dying in men without prostate cancer, suggesting that the molecules were specifically influencing the odds of dying from cancer rather than from any cause in general. Since these were the same molecules that were elevated in cancer-free African American men compared to European men, they could be important contributors to racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes.

“We think what we are discovering here are factors outside of the tumor, in the blood, that are perhaps very important for the process of metastasis,” Dr. Ambs explains. “Clinicians don’t look at that as much as they are studying the environment immediately surrounding the tumor, and I think that could be a mistake.”

Dr. Stefan Ambs

Finally, the study revealed that the levels of two molecules, called TNFRSF9 and pleiotrophin, could be used to predict the likelihood of prostate cancer being lethal in African American patients with an accuracy of just under 80 percent. One-third of African American patients with high concentrations of both molecules in their blood died within 10 years of their cancer diagnosis, whereas only one in twenty African American patients with low levels of either died in that time span. On the other hand, the researchers could not predict the risk of death in European American or Ghanaian patients based on the results of their blood analysis. For the Ghanaian patients, this was because there was no long-term follow-up on them, so there was no way to know which of them had died, while for the European Americans, it may have been because relatively few of the study’s European American patients died from their cancers. Despite these limitations, the data suggest that TNFRSF9 and pleiotrophin are more closely related to prostate cancer in African American than European American men.

If additional studies confirm that levels of TNFRSF9 and pleiotrophin are predictive of prostate cancer metastasis and death, it may be useful to measure those proteins in African American prostate cancer patients and tailor therapy accordingly. The study also suggests that treatments that remove the brakes inhibiting the immune response to cancer, as certain immunotherapies do, could be particularly effective in African American patients.

“I think we really did discover something that could turn out to be important for reducing health disparities, and it could be something that could be taken on by clinicians,” Dr. Ambs says. “People have looked at prostate cancer immunotherapy, and it does not work well because there are not many markers on the tumor for the immune system to target, but there are differences between African Americans and European Americans, and one has to look to see if, in African Americans, it works much better. I think people should look in the blood for targets that influence the response to immunotherapy and go after those targets, and that could make a difference.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Minas TZ, Candia J, Dorsey TH, Baker F, Tang W, Kiely M, Smith CJ, Zhang AL, Jodran SV, Mobadi OM, Ajao A, Tettey Y, Biritwum RB, Adjei AA, Mensah JE, Hoover RB, Jenkins FJ, Kittles R, Hsing AW, Wang XW, Loffredo CA, Yates C, Book MB, Ambs S. Serum proteomics links suppression of tumor immunity to ancestry and lethal prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2022 Apr 1;13(1):1759. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29235-2.

[2] Giaguinto AN, Miller KD, Tossass KY, Winn RA, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022 May;72(3):202-229. doi: 10.3322/caac.21718.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023