PIs Pursuing Their Passions

From Pencils to Pinnacles

NIH scientists have a variety of interests outside of work. Many enjoy hiking, dancing, running, gardening, and other activities. Here are a few PIs we thought had particularly interesting “extramural” pursuits.

Elodie Ghedin (NIAID), who develops tools to define the genetic structure and mechanisms of evolutionary change in respiratory viruses, loves to cartoon in her spare time. Sergi Ferré (NIDA), who studies receptors as targets for drug development in neuropsychiatric disorders, is an operatic tenor and sings with his wife (who’s a soprano and a scientist) at all kinds of venues. Katie Kindt (NIDCD), who uses zebrafish in her investigations of hair cells in the inner ear, loves to rock climb. Joseph M. Ziegelbauer (NCI), who studies Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, has a telescope equipped with a special camera that takes out-of-this-world photos of the stars. And a pair of NIH investigators summit alpine mountains together all over the world: Edward Giniger (NINDS), who studies how neural wiring develops and disassembles during neurodegenerative disease; Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré (NHLBI), who investigates the function of RNA molecules in their many guises.

Read on to learn more about them.

The Cartoonist

Elodie Ghedin, Ph.D.

Senior Investigator and Chief, Systems Genomics Section, and Deputy Chief, Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Research: Developing tools to define the genetic structure and mechanisms of evolutionary change in respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, with a current goal of building predictive models of COVID-19 severity

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/elodie-ghedin

Hobby: Cartooning

Fun Facts:

- Favorite storyline: The main character appears clownish or comical at first glance but has unusual superhero qualities.

- Cartoonists who inspired her: French cartoonists Claire Bretécher and Marcel Gottlieb (known professionally as Gotlib)

- Favorite artist tools: Sakura Pigma Micron pens

- Most surprising about cartooning: Sometimes, a random stroke of your pencil or pen takes you in an unexpected direction and characters start having a life of their own.

CREDIT: STEVEN HODAK

When she’s not working in the lab, Elodie Ghedin enjoys drawing humorous cartoons.

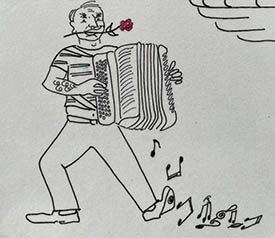

Elodie Ghedin’s mother was a model and beautician, and her father owned a business designing and building beauty appliances. But in the cartoons Ghedin creates, her parents have alter egos: Her mom is a French spy who fixes the world’s fashion faux pas; her dad is a secret agent, masquerading as a musician, protecting his designs. (He played the accordion in real life.) Ghedin’s cartoons center on her family’s inside jokes and the situations they get into. Inspiration can strike at any moment.

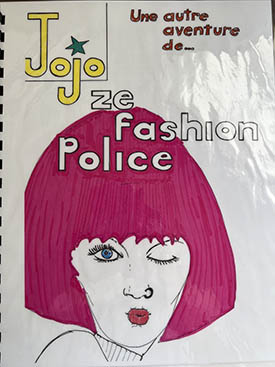

The funny stories that Ghedin’s family members share about their lives have been the source of many of her cartoons. She keeps a running list of scenarios based on real-life events. When a family member’s birthday approaches, she chooses a few of the scenarios to weave together into a short storyline. For example, her Jojo the spy cartoons were inspired by the time her mother, Joelle, wore a punk outfit, complete with a pink wig, nose ring, leather skirt, and Dr. Martens lace-up leather boots to meet Ghedin’s husband for the first time. In the cartoons, Jojo is wearing that exact outfit with a complement of spy gadgets including an eyelash curler that doubles as a camera and a secret message receiver.

CREDIT: ELODIE GHEDIN, NIAID

Ghedin’s mother, Joelle, was the inspiration for a cartoon series about French spy Jojo, a member of the fashion police.

After figuring out a storyline, Ghedin drafts a cartoon with pencils and then traces the figures with a fine-point black marker. Then she adds pops of color, such as to eyes or pieces of clothing. Capturing the expressions of real people and distilling them into cartoon characters is one of the challenges of the process, since adding a few extra lines can drastically change how a character looks. Deciding the specific scenes to include in each panel is also tricky.

“The reader has to sort of guess what action happened between Panel A and Panel B,” said Ghedin. “You don’t want to have too many panels, and not too few either.”

CREDIT: ELODIE GHEDIN, NIAID

One of Ghedin’s cartoon series features her father as a French secret agent whose cover is being a musician.

To Ghedin, what makes the hours that go into her creations worthwhile is seeing her family members’ reactions when they look at her cartoons. Some people have even framed and hung her cartoons in their homes, and they often ask when she will draw them another one.

“When you make people laugh, when you see they’re happy with it, that’s the most rewarding,” Ghedin said.

The Opera Singer

Sergi Ferré, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Investigator and Chief, Integrative Neurobiology Section, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)

Research: Studying G protein–coupled receptor heteromers (macromolecular complexes of different interacting receptors and specific biochemical properties) as targets for drug development in neuropsychiatric disorders, including substance-use disorders.

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/sergi-ferre

Hobby: Opera singing (tenor)

Fun Facts:

- His repertoire includes arias and duets from famous operas (including ones by Giacomo Puccini, Giuseppe Verdi, Georges Bizet, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Gaetano Donizetti, Ruggero Leoncavallo, Pietro Mascagni, and Jules Massenet)

- Favorite arias: “Che gelida manina” (La Bohème), “Nessun dorma” (Turandot), “Vesti la giubba” (Pagliacci), “Una furtiva lacrima” (L’Elisir d’Amore)

- Favorite duets: “O soave fanciulla” (La Bohème), “Brindisi” (La Traviata), “Au fond du temple saint” (Le Pêcheurs de Perles)

- Favorite quartet: “Bella figlia dell’amore” (Rigoletto)

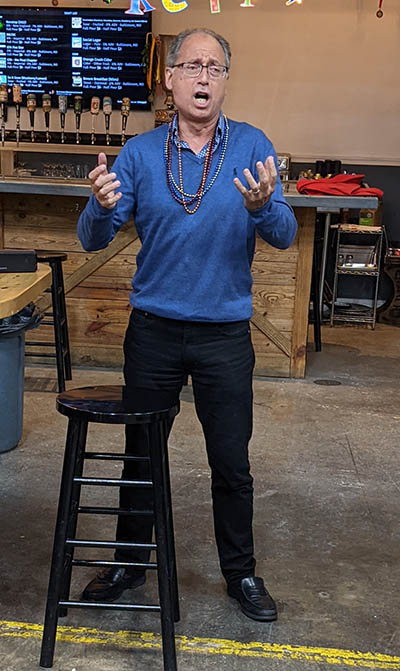

COURTESY OF: SERGI FERRÉ, NIDA

Sergi Ferré, a tenor, enjoys singing opera at different venues, including at a colleague’s retirement party.

Opera has always been a part of Sergi Ferré’s life. His mother was a piano teacher and his parents loved opera, fostering in him a special connection with music from a young age. Growing up in Barcelona, Spain, Ferré even saw the debut of the famous operatic tenor, and Barcelona native, José Carreras in the Gran Teatre del Liceu (Barcelona’s Opera House). For years, however, opera singing remained at the back of Ferré’s mind. It wasn’t until he moved to the United States more than 20 years ago—to become a research fellow at NIDA—that he began to pursue the possibility of singing opera.

During his commute to work each morning, Ferré would listen to opera music and try to imitate what he heard. It was then that he realized he could hit the high notes required for the tenor register. Challenging himself to reach higher notes and improve his pitch, he was soon able to surprise his family and friends with his singing.

Then, in 2010, Ferré struck an informal deal with NIDA’s scientific director, Barry Hoffer, who was an opera lover, too. One day, Ferré joked that he could sing the opera music Hoffer played in his office. Hoffer responded that if Ferré could perform a particular aria from the opera La Fille du Régiment, which requires hitting five high-C notes, then he would promote Ferré to senior investigator (he was a tenure-track investigator at the time). Holding up his side of the deal, Ferré prepared three arias to perform at Hoffer’s 70th birthday party, leaving the one that he had bet upon until the end. To Hoffer’s surprise, Ferré performed the arias, reaching all the high notes. Ferré was promoted…based on his job performance…in 2012.

Ferré’s talent led to love as well. NIDA senior investigator Elliot Stein watched Ferré’s performance at Hoffer’s birthday party and later told one of his postdocs, who was also an opera singer, about it: Annabelle (Mimi) Belcher. Belcher, a soprano, reached out to Ferré, and they began to perform duets with each other in 2010—their first gig was in December at a NIDA holiday party.

COURTESY OF: SERGI FERRÉ, NIDA

At their wedding, Sergi Ferré and his wife Mimi sang the duet “Brindisi” from La Traviata, an opera by Giuseppe Verdi. They perform together regularly at local restaurants and other venues in an effort to dispel the stiff and formal atmosphere that’s often associated with opera and to convey the beauty of the music.

Bonding over their shared passion for music, Ferré and Belcher fell in love and were married in 2012. Belcher is now an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (Baltimore).

It’s been more than 20 years since he first began to sing opera, but Ferré’s love for it is still going strong. He and his wife used to host regular opera nights at a small Baltimore restaurant, where they tried to dispel the stiff and formal atmosphere that’s often associated with opera and to convey the beauty of the music. The venue has since closed but they’re still performing wherever they can.

“And then comes the big reward,” said Ferré. “The applause, someone with tears in the eyes, or someone saying, ’I did not know I liked opera!’”

To hear a recording of Sergi Ferré singing an aria, go to https://youtu.be/ypvW9wQuLsA.

The Rock Climber

Katie Kindt, Ph.D.

Senior Investigator and Chief, Section on Sensory Cell Development and Function, National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders

Research: Investigating the development and function of hair cells in the inner ear using zebrafish, which are transparent and can be studied in vivo.

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/katie-kindt

Hobby: Rock climbing (and mountain biking)

Fun Facts:

- Favorite climb: Tunnel Vision at Red Rock Canyon (near Las Vegas), where you climb through tunnels for a portion of the route

- Most unusual piece of climbing gear: A Big Bro, which is an expanding metal tube that can be slotted into large cracks for protection when lead climbing.

- Most memorable climb: The top of “High Exposure,” a classic climb in the Gunks (near New Paltz, New York) where she got engaged; later she spontaneously got married in Las Vegas when a snow storm ended a climbing trip in Red Rocks, Nevada.

- Memorable climb: West ridge of Mount Conness near Yosemite National Park (in California) where she was “benighted” (overtaken by darkness); after completing the climb she had to make an unplanned bivouac overnight in the wilderness.

- Memorable climb: “Right On” at Joshua Tree National Park (in California) because it is the first multipitch climb she and her husband and took their son up (he was 7 at the time).

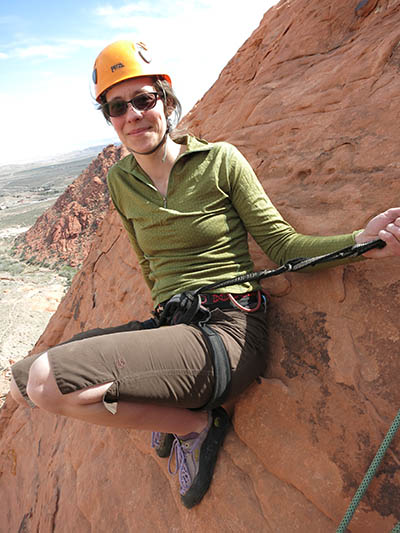

CREDIT: ALAIN SILK

Katie Kindt climbing in Red Rock Canyon near Las Vegas.

Many people have an outlet for stress, in which they can channel their energy into a single task and tune out distractions. For some, this outlet might be running, journaling, dancing, or creating art. For Katie Kindt, it’s rock climbing. When she climbs, she doesn’t think about anything else—losing her concentration could result in a fall.

Kindt started rock climbing when she was a graduate student at the University of California at San Diego (San Diego). After trying out different activities, she found that the outdoor ones, such as rock climbing, camping, and mountain biking, appealed the most to her. With that in mind, Kindt and a few other students would meet every Wednesday with a local climbing group, who showed them how to climb and set up climbs safely. Nowadays, Kindt regularly climbs with other scientists at NIH, members of her lab, and her family. A few days a week, she’ll head to the Movement Rockville indoor climbing gym (Rockville, Maryland). Weather permitting, she’ll sometimes climb outside at Great Falls National Park (McLean, Virginia) or at Carderock Recreation Area (Potomac, Maryland), both of which are located along the Potomac River.

Kindt uses a style of climbing called top roping at these local climbing spots, making the climb rather straightforward. With top roping, the climber is attached to a rope running through an anchor that’s already at the top of the route so they are always supported from above. But she often does lead climbing when she’s out West: The lead person wears a harness attached to a rope, which in turn is connected to other climbers below. Lead climbing is more difficult and dangerous because the lead climber must set up their rope and place protection equipment—permanent bolts or removable nuts and cams—into the climbing wall as they are ascending.

CREDIT: ALAIN SILK

Katie Kindt likes to mountain bike, too.

In the spring, Kindt usually takes a climbing trip to Red Rock Canyon near Las Vegas or Joshua Tree National Park in southern California. Between taking in the desert scenery and focusing on the climb, she never forgets the gravity of the process she’s undertaking.

“It’s good to remind yourself that you’re hundreds of feet up in the air,” she said. “Like, you should be afraid [and] take this seriously.”

The Astrophotographer

Joseph M. Ziegelbauer, Ph.D.

Senior Investigator, HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch, National Cancer Institute

Research: Studying Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, which expresses multiple microRNAs that modulate human gene expression. A goal is to determine the targets of viral microRNAs and understand why the virus has selected these specific target genes for inhibition.

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/joseph-ziegelbauer

Hobby: Astrophotography

Fun Facts:

- Farthest away astronomical object that he’s taken a photo of: a galaxy that is 100 million light-years away

- Longest acquisition time for a photo: 30 hours for the Jellyfish Nebula

- Favorite galaxy: Whirlpool Galaxy (it is two galaxies colliding)

- Most surprising thing: That he can capture a faint nebula in his yard despite the light-polluted skies (using the appropriate filters)

- Other: Slept in his car next to his telescope many times

- Best photos: Some of his best are on Twitter @DrJZ_

CREDIT: JOSEPH M. ZIEGELBAUER, NCI

Joseph M. Ziegelbauer, an astrophotographer in his spare time, uses a camera connected to a telescope to capture dramatic photos of the night sky.

Five years ago, Joseph Ziegelbauer’s wife bought him a telescope, thinking that astronomy would be something that would interest him. Her guess was right. Since that first telescope, Ziegelbauer has moved from observing objects in the night sky to capturing them with a camera, creating vivid, out-of-this-world photos.

It’s been a constant learning process for Ziegelbauer. He first had to figure out the basics—how to connect a camera to the telescope, how to take sequences of images over long stretches of time, and how to stack images to produce sharper photos. With help from discussion forums, YouTube videos, and other online resources, Ziegelbauer has gradually optimized his photography process, such as by using a Raspberry Pi minicomputer to automate taking photos and upgrading his camera to one specifically designed to work with telescopes.

“A pleasant surprise has been the community of astrophotographers,” he said. “You can just post a question, and people will take time to answer your superspecific questions.”

From setting up the telescope to processing the images, it takes him roughly 30 hours to create a final image.

CREDIT: JOSEPH M. ZIEGELBAUER, NCI

Ziegelbauer gets out-of-this-world photos of places like the Orion Nebula.

Among the photos he’s taken, capturing the great conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in December 2020, in which the two planets appeared the closest together in nearly 400 years, was the most difficult. Ziegelbauer needed to capture Jupiter, Saturn, and the moons of both planets in the same frame within a very short window of time, and because the objects differ in brightness, each required a different exposure. The images then needed to be layered on top of one another for each object to be seen clearly.

To Ziegelbauer, the biggest challenge in astrophotography is really a series of smaller ones. Is the sky cloudy? Is the moon visible? Are there trees or other objects blocking the view? These are among the variables that he must account for to produce the cleanest shot. Processing the raw image sequences requires lots of fine-tuning as well. Ultimately, however, what makes it all worth it to Ziegelbauer is seeing the cumulation of his effort.

“When you see that first image pop out of the computer after hours and hours of image processing, there have been multiple times when I’ve literally gasped looking at the screen,” he said.

The Mountaineers

Edward Giniger, Ph.D.

Senior Investigator, Axon Guidance and Neural Connectivity Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Research: Studying neural wiring: how it is established during development and why it is disassembled during neurodegenerative disease.

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/edward-giniger

Hobby: Alpine mountaineering (with Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré)

Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré, Ph.D.

Senior Investigator, Laboratory of RNA Biophysics and Cellular Physiology, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Research: Investigating the function of RNA molecules in their many guises, the interactions between RNA and proteins at the atomic level, and the role of RNA molecules in gene regulation and signal transduction.

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/adrian-ferre-damare

Hobby: Alpine mountaineering (with Edward Giniger)

Fun Facts:

- Favorite climbing proverb: “There are old climbers and there are bold climbers, but there are no old bold climbers.”

- Highest mountain climbed together: Petite Aguille Verte in France

- Name some of the mountains you climbed: Aguille de l’M in France; Eldorado Peak and Mount Shuksan in Washington); Mount Athabasca, Mount Victoria, and Pigeon Spire in Canada

- Hardest climb and why?: Pigeon Spire in Canada, not because of the climb itself, but because the steep glacier on the way back to the mountain hut had melted so much that the route had become a challenging descent on abrupt, disintegrating rock–and, we had to navigate this by headlamps well after sunset.

- Easy dinner recipe: To prepare couscous in a Ziploc bag, add boiling water; close zips securely and wrap in down jacket until hydrated; season with curry powder and raisins; top with tuna from a pouch.

- Average daily calories consumed when on a climbing trip: 4,500

- Most unusual “climbing gear”: Big roll of chicken wire mesh wrapped around the car left at the trailhead to the Bugaboo Mountains (Canada). The local porcupines love to chew through engine hoses, which apparently taste salty to them.

CREDIT: ADRIAN R. FERRÉ-D’AMARÉ, NHLBI

Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré (left) and Edward Giniger on a spring conditioning climb in the North Cascades of Washington state. Mounts Shuksan and Baker are in the background.

At 2:00 a.m., many of us are fast asleep in our beds, trying to get a good night’s rest. But thousands of feet up in the mountains, the day is just beginning for Edward Giniger and Adrian Ferré-D’Amaré, who have summited mountains throughout Europe and North America. After scrambling to eat breakfast and double-checking that they have all the equipment they need, they head out in the dark to begin their climb.

Giniger and Ferré-D’Amaré discovered their mutual interest in climbing when they met as faculty members at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. Giniger had taken classes from local hiking clubs, gaining experience with ice climbing and rock climbing. Ferré-D’Amaré “inherited” his passion for mountaineering from his grandfather, who had emigrated from Catalonia (in northeastern Spain) to Mexico, where he loved to ascend the glacier-covered volcanoes scattered around Central Mexico.

For their first expedition together, Giniger and Ferré-D’Amaré summited Mount Hood, the highest mountain in Oregon. In the years since, the duo has climbed the European Alps, scaled the Canadian Rockies, and ascended mountains throughout the United States. They’re hoping to take more mountaineering trips in the future.

An alpine mountaineering trip is a multiweek event. It takes several days for the body to acclimate to the high altitude and thinner air before the actual climb begins. In the United States, Giniger and Ferré-D’Amaré hike for a couple of days to get in shape before tackling a mountain. In Europe, however, cable cars can transport them to higher elevations to the edge of a glacier in just a few hours. Unlike most climbing areas in the United States where climbers must set up camp and carry their own their supplies, areas in Europe and Canada have well-organized mountain hut systems with basic amenities, like beds, central heating, and meals that make the climbing experience easier.

CREDIT: ADRIAN R. FERRÉ-D’AMARÉ, NHLBI

Edward Giniger standing on Mount. Shuksan in North Cascades National Park in Washington state (2009)

CREDIT: : ADRIAN R. FERRÉ-D’AMARÉ, NHLBI

Adrian R. Ferré-D’Amaré sitting atop the Grand Teton Mountain in Jackson, Wyoming (2014).

When they are dealing with snow-covered mountains, Giniger and Ferré-D’Amaré prefer an “alpine start,” which means leaving their camp or hut in the middle of the night when the ice and snow are still frozen. Once the sun rises and the air warms, the thin crust of ice on the surface melts causing the climbers to sink into the snow with every step. There’s also more risk when melting ice dislodges snow (as avalanches), ice, and rocks. And getting an early start means that they’ll return to camp when it’s still light outside and won’t be stumbling back—hungry and exhausted—in the dark.

For experienced climbers, mountaineering is not necessarily more dangerous than other sports, said Ferré-D’Amaré. It’s up to the climbers to decide the level of risk they’re comfortable with—based on the strength and abilities of the climbing party, weather conditions (and knowing that conditions may rapidly change), and other factors. Global warming adds another layer of complexity—many historically famous alpine climbing routes have already collapsed.

Despite the risks, Giniger and Ferré-D’Amaré find alpine mountaineering rewarding for a combination of reasons. There are the beautiful views and the physical exertion. There’s the teamwork, as well as having to problem solve and constantly reassess a climb based on changing variables.

The Zenlike mindfulness that comes with having to concentrate on the present is also a draw for the pair, “especially for people like us who think way too much,” Giniger said.

Victoria Tong, a Pathways editorial intern for the summer at The NIH Catalyst, just began her freshman year at the University of California-Los Angeles and expects to major in chemistry. She was the editor of the student newspaper at Richard Montgomery High School in Rockville, Maryland. In her free time, she enjoys playing tennis, solving crossword puzzles, and scoping out new restaurants.

This page was last updated on Monday, September 19, 2022