From the Annals Of NIH History

Radiation Exposure Among Early NIH Workers

Dosimetry Cards and the History of Radiation Safety

The following is based on a historical overview provided by Michael Roberson, Deputy Director of the Division of Radiation Safety.

When we think of radiation exposure, large nuclear disasters may come to mind. But people who work with radioactive materials in medical settings can be exposed daily to small amounts of radiation that may accumulate over time, resulting in a small increase in cancer risk. NIH researchers, clinicians, and other staff have been working with radioactive materials and radiation-emitting devices since the 1940s, when it was routine to use radium needles for cancer therapy, run radium-radon generators that converted radium to radon for cancer treatments, or operate X-ray machines that produced ionizing radiation.

Today, radiation exposure is still a concern in certain biomedical research labs, during radionuclide production and fluoroscopic clinical procedures and, less so, from diagnostic imaging such as computed tomography, mammography, and nuclear imaging. To ensure exposure limits are not exceeded, some medical and research personnel (those who might exceed 10% of the allowable limit) wear dosimeters, devices that measure cumulative radiation exposure.

Early days of radiation safety

CREDIT: LAURA S. CARTER, OD

Dosimeters come in all shapes and sizes. Clockwise from left: film badge holder that can fit on a wristband, badge to measure whole-body radiation exposure, two ring dosimeters, and pocket dosimeter.

Radiation safety was formalized in 1947 at NIH when then–NIH Director Rolla E. Dyer issued the “Precautions for Protection from Radiation at the National Institute of Health,” noting that they would be updated as more stringent guidelines were imposed and permissible exposure was lowered. In 1948, Dyer appointed a Radiation Safety Committee to conduct inspections of work areas that were using radioactive substances or radiation-producing equipment and to issue radiation-safety recommendations for people working in those areas.

Methods to detect radiation exposure

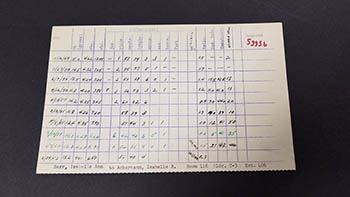

Before 1950, NIH employees who worked with radioactive materials underwent blood draws semiannually that were analyzed to see whether significant decreases had occurred in white-blood-cell and platelet counts. This method was phased out by the mid-1950s and was replaced by film badges and personal dosimeters, which detect high-energy beta, gamma, or X-ray radiation. The results were recorded on index-card-sized cards called dosimetry cards.

CREDIT: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY

Blood analysis card for Isabelle Barr Ackerman, the first woman radiation safety professional at NIH. Before 1950, people who worked with radioactive materials had their blood drawn semiannually and it was analyzed to see whether significant changes had occurred in certain blood elements.

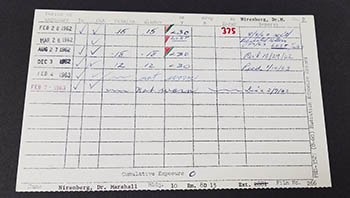

As part of an effort to preserve NIH’s history of radiation safety, the NIH Division of Radiation Safety recently donated about 100 of its 27,000 record cards—including several with blood analysis results—to the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum. The collection includes dosimetry cards from well-known NIHers: Donald Frederickson long before he became the director of NIH in 1975; Isabelle Barr Ackerman, the first woman radiation safety professional at NIH; and 1968 Nobel Laurate Marshall Nirenberg.

CREDIT: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY

Marshall Nirenberg’s dosimetry card. Nirenberg, along with two other researchers, jointly received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1968 for discovering the key to deciphering the genetic code. He was the first federal scientist to receive a Nobel Prize.

The card system was used from the 1940s to the late 1970s for employees to record their cumulative external exposure to radiation. On September 25, 1950, 89 workers began wearing film badges at NIH. In addition, researchers in Building 21’s hot labs (labs that used radioactive materials) were issued self-reading quartz-fiber pocket dosimeters, which could detect radiation exposure in real time. (The information from other types of dosimeters had to be processed before the radiation exposure was known.) The film badges, which were worn on the chest for whole-body measurement and wrist for extremities, had to be exchanged every two weeks to be processed and analyzed. Finger film badges were introduced by July 1975, but wrist badges were still used until at least 1979. The pocket dosimeters, which were worn on the chest or waist, could give a relatively good estimate of exposure in real time without having to wait for processing. This information was then recorded on a dosimetry card for each person.

The earliest film badges, however, were not very sensitive. For a radiation dose to even register, it had to be at least 50 millirems (mrem). Anything below this level would register as no exposure, so in the early years, workers might have received much more radiation than was recorded. The sensitivity of the dosimeters improved to 30 mrem by October 1952 and to 10 mrem in April 1963. These measurements were manually recorded on the dosimetry cards until 1979, when an early computer system took over.

That computer system evolved into today’s Radiation Safety Comprehensive Database. The dosimeters have also improved: Film badges were replaced in 1994 by thermoluminescent dosimeters (TLD), with a sensitivity of 1 mrem; TLDs were replaced in 2003 by optically stimulated luminescence dosimeters, which also have a sensitivity of 1 mrem.

Through the years, the federal limits for occupational radiation exposure have decreased. Prior to 1950, the limit was 25,000 mrem per year; after 1950, it was lowered to 15,000 mrem; since 1957, the limit has been 5,000 mrem per year. For some context, today a single chest X-ray produces approximately 2 mrem.

Radiation safety at NIH has evolved since its implementation in the 1940s. Today, NIH’s Division of Radiation Safety ensures the safe use of all radioactive materials and sources of ionizing radiation throughout NIH, provides training courses for workers using radioactive materials, and requires the use of personal dosimeters in certain areas.

Haley Higingbotham is a Pathways intern in the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum. She recently graduated from George Washington University (Washington, D.C.) with a master’s in museum studies specializing in collections management. She is helping to maintain and process the history office’s archival collections, make physical and digital collections accessible to researchers, answer reference requests, and transcribe oral histories. Outside of work, you can find her reading fantasy novels or exploring the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area.

This page was last updated on Monday, September 19, 2022