Saliva Suspected in Transmission of Intestinal Viruses

Nihal Altan-Bonnet’s Research on Host-pathogen Dynamics

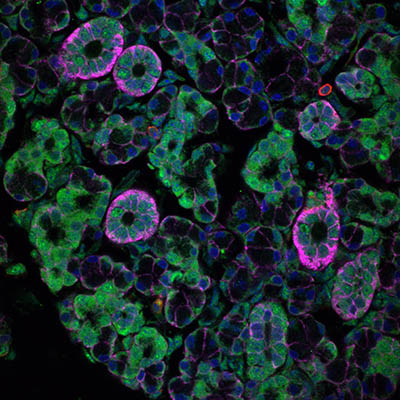

CREDIT: NIHAL ALTAN-BONNET, NHLBI

Researchers have shown in mouse studies that enteric viruses, which can cause severe diarrheal diseases, can grow in the salivary glands and spread through the saliva. Shown: microscopic view of salivary gland acinar epithelial cells (pink) infected with rotavirus (green), a type of enteric virus, in a mouse.

Why do outbreaks of gastrointestinal illnesses spread so rapidly among passengers on cruise ships? How can norovirus, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists as a leading cause of acute gastroenteritis, infect nearly 700 million people each year worldwide? A newly discovered route of enteric (intestinal) virus transmission may be the culprit. Enteric viruses such as norovirus and rotavirus reproduce in the intestines and are known to spread via the fecal-oral route (when fecal-contaminated food or water is ingested). The viruses often cause vomiting and acute diarrhea, and they can sometimes be deadly.

A trans-NIH team of researchers, led by Senior Investigator Nihal Altan-Bonnet (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), has learned that saliva can be a transmission vehicle, too. Their findings were published in Nature (Nature 607:345–350, 2022).

Health experts have traditionally recommended regular hand washing and sanitizing surfaces as ways to mitigate transmission of common enteric diseases. But the new findings suggest that talking, coughing, sneezing, and kissing could also contribute to disease spread and that extra precautions, such as wearing masks, might also be indicated.

Previous research by Altan-Bonnet’s team uncovered mechanisms whereby norovirus and rotavirus egressed from cells. In the new study, the team used female mice and their infant pups as a model to study disease transmission between animals.

CREDIT: DIVISION OF INTRAMURAL RESEARCH, NHLBI

NHLBI Senior Investigator Nihal Altan-Bonnet found that saliva is an unexpected route of transmission for gastrointestinal illnesses such as norovirus.

“We started using animal models to look at these enteric infections, and certain things in our experiments gave us a hint that transmission may not be solely through the fecal-oral route,” said Altan-Bonnet.

First, infant mice were orally inoculated with a norovirus or rotavirus and then allowed to suckle their virus-free mothers. Shortly after, the scientists noticed something unusual—a rapid and large spike in secretory immunoglobulin (sIgA, a disease-fighting antibody found on mucous membranes) in the immature mice intestines. The immune systems of the mouse pups were not expected to make their own antibodies at this young age. Moreover, the mammary tissue and the milk of the mothers whose infants were infected had high concentrations of sIgA and were found to be infected with the same virus.

How could the mammary glands be infected if enteric viruses are spread solely through the fecal-oral route as previously thought? It seemed that the infant mice had passed their infection to their mothers’ breasts through saliva while suckling, which then boosted the production of virus-fighting sIgA antibodies in the breast milk. The curious results prompted further experiments.

Mouse pups were again orally inoculated with a virus and allowed to breastfeed on their birth mothers. Then, these pups were replaced with a litter of noninfected pups that were permitted to suckle from the newly infected mothers. To the surprise of the research team, the previously uninfected pups now became infected and had high viral loads not only in their intestines but also in their saliva and salivary glands. This supported the notion that suckling had caused both pup-to-mother and mother-to-pup viral transmission. Notably, the pup salivary glands replicated these viruses to concentrations on par with what’s in their gut. Additionally, removing the pups’ salivary glands allowed for a quicker clearance of infection in their gut, suggesting that the salivary glands may be reservoirs for these viruses.

The new discovery may have important implications for therapeutics and diagnostics for enteric diseases and inform sanitation measures to reduce transmission through saliva.

“Follow where the data [lead] you and don’t make any assumptions,” said Altan-Bonnet, adding that naming these viruses “enteric” may draw an incomplete picture of how they spread. She looks forward to future research to uncover how these viruses replicate in humans.

Stephen Andrews, a postbaccalaureate research fellow in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, is studying protein-antibody interactions related to systemic capillary leak syndrome, or Clarkson disease. Outside of the laboratory, he enjoys running, cycling, cooking, and visiting art galleries.

This page was last updated on Monday, September 19, 2022