The Dermatology Branch at NIH

Research, Colleagues, and a Shift from NCI to NIAMS

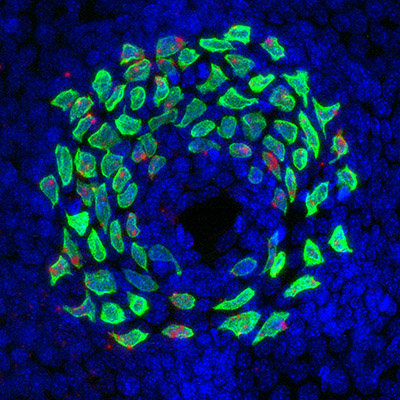

CREDIT: ISAAC BROWNELL AND LINGLING MIAO, NIAMS

Merkel cells are clustered in touch-sensitive areas called touch domes. Shown: Neonatal mouse touch dome; Merkel cells in green.

In Spring 1975, desperate parents brought their six-year-old daughter to the NIH Dermatology Branch to be treated for a rare, chronic skin disease—coupled with arthritis—that had plagued her for more than four years and was making her miserable. Her doctors “were at the end of the line in terms of what to do,” said Stephen Katz in a 2018 oral-history interview. He was a senior investigator in 1975 and had joined the Dermatology Branch, which was then part of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), only the year before. “She had been treated with everything.” He biopsied some of the affected areas of her skin and scheduled her to return in July for a follow-up visit.

After analyzing the biopsied tissue and conferring with his brother, who was also a dermatologist, Katz determined that the child had a rare disease called erythema elevatum diutinum. It’s characterized by painful, necrotizing vasculitis that causes thick red, purple, brown, and yellow patches on knees, elbows, hands, and other areas of the body. He had even come up with a plan for how to treat it. “I knew that this rare disease responded to a drug that wasn’t usually included when one says, ‘She was treated with everything,’” said Katz. “This is a drug called dapsone, which was otherwise used [for] treatment of leprosy.” Colleagues laughed in disbelief when Katz told them what he had in mind.

But when the girl returned for her follow-up visit on the July 4 weekend, Katz did treat her with dapsone and within a couple of days, she was 98 percent better, he said. “She’s been on that drug for 40-some years because if she stops [using it], the disease comes back.” To this day, dapsone is the first line of treatment for this rare disease.

CREDIT: NIAMS

NIAMS Director Stephen Katz, who died on December 20, 2018, was a leader in the study of skin-based immunology and trained more than 45 people who have gone on to play significant roles in dermatology.

Katz, who died in December 2018, became the chief of NCI’s Dermatology Branch in 1980 and served in that capacity until 2001 even after being made Director of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) in 1995. During his tenure as chief, the branch grew into a formidable force and trained dozens of scientists who went on to assume leadership positions in dermatology departments throughout the world—including Germany, Austria, England, Hungary, Belgium, Switzerland, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and the United States. He’s also largely responsible for building an awareness that the skin is an important part of the body’s immune system and that abnormalities in the immune system are associated with many skin diseases. His own research included discovering an antigen associated with autoimmune blistering skin diseases.

Under Katz’s guidance, Dermatology Branch scientists have made many discoveries including the:

- Pathogenesis of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), a genetic disease that makes cancer more likely and is associated with developmental abnormalities and cellular hypersensitivity to ultraviolet radiation

- Use of synthetic retinoids to treat severe disfiguring acne and as chemoprevention agents

- Composition and function of the skin immune system with special emphasis on Langerhans cells

- Cytokines and chemokines that mediate cutaneous inflammation

- Structure of adhesive junctions that mediate the attachment of keratinocytes to each other and to underlying basement membranes

- Characterization of patient autoantibodies that react with adhesive structures and that cause skin-blistering diseases

- Characterization of dendritic-cell HIV interactions; identification of mechanisms that regulate leukocyte and cancer-cell localization

- Characterization of normal tissue and cancer stem cells

Early Dermatology Research

Dermatology research was being conducted at NIH as far back as the 1930s, before NIH was divided into institutes and centers (ICs). The Division of Industrial Hygiene, for example, investigated the health of workers in different industries. In 1939, the division’s scientists described industrial dermatitis (redness, itchiness, cracking, and blistering of the skin caused by tar and other substances used at work) and melanosis (a form of hyperpigmentation caused by increased melanin). The research led to procedures for protecting workers’ skin. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and then the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (part of CDC) and the Environmental Protection Agency, have taken over much of what the division used to do.

NIH’s Division of Infectious Diseases, led by Rolla E. Dyer, focused on a wide range of diseases caused by bacteria, viruses, and fungi. In 1934, Chester Emmons, an expert on fungi as a cause of disease, established the current classification system of the taxonomy of dermatophytes (fungi that infect the hair, skin, and nails, causing ringworm).

CREDIT: PIERRE ARENTS, CREATIVE COMMONS

Early dermatology research at NIH included studies of leprosy. Shown: Twenty-four year old man from Norway, suffering from leprosy.

The Division also studied leprosy (today, Hansen disease), a contagious disease caused by a Mycobacterium species that affects the skin, nerves, and eyes. In Hawaii, the division’s Leprosy Investigation Station invented orthopedic devices to correct deformities caused by nerve damage and found that malnourishment (particularly deficiencies in vitamin B1 and calcium) increased susceptibility to leprosy. It was not until the late 1940s that the causative organism was found and an antibiotic treatment for leprosy was developed.

Beginning in 1937, NCI (which had been established by Congress as a separate entity within the Public Health Service and became a division of NIH in 1944) funded a Public Health Methods study on the number and characteristics of cancer deaths in the United States using records dating back to 1900. Among the findings were that although more people in the northeast died of cancer, more people in the South had cancer. The scientists thought the difference was because of the greater prevalence of skin cancer in the South.

Dermatology Branch Founded in the 1960s

There wasn’t a formal Dermatology Branch at NCI until 1961, when Eugene Van Scott became its first chief. He left NIH in the late 1960s to head Temple University’s (Philadelphia) dermatology department and later founded a company that became a major skin-care corporation. His work on psoriasis led to the development of methotrexate, which is to this day a first-line systemic drug for its treatment. He also won a Lasker Award in 1972 “for his outstanding contribution to the concept of topical chemotherapy in the treatment of mycosis fungoides” (the most common form of the skin-cancer cutaneous T-cell lymphoma).

Marvin Lutzner became branch chief next. He and two French dermatologists discovered Lutzner cells, a mutated form of T lymphocytes. Lutzner cells can cause cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that starts as skin lesions and may eventually spread to other parts of the body. During his tenure, he collaborated on XP research with other NCI scientists, including Kenneth Kraemer who was a postdoc in the Dermatology Branch (and a commissioned officer in the U.S. Public Health Service) in the early 1970s and is now a senior investigator in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics. Kraemer is continuing this work and recently found that the molecular changes in skin melanomas from XP patients were closely related to sun exposure and different from those of skin melanomas in the general population. NIH’s 40 years of research on XP are highlighted in an article by Kraemer that appeared in the journal Photochemistry and Photobiology (Photochem Photobiol 91:452–459, 2015).

In 1969, Lutzner recruited Gary Peck, who studied how retinoids could change epidermal differentiation from keratin-producing to mucus-producing. Electron-microscopy studies with Peter Elias, currently a world-renowned skin biologist at the University of California at San Francisco, elucidated the ultrastructural changes of retinoic-acid-induced mucous metaplasia. Their work led to a broad clinical trial of systemic retinoid treatment. In 1980, John DiGiovanna came to NIH from the University of Miami (Coral Gables, Florida) and worked on characterizing the pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and toxicities of retinoid therapies. Early studies showed that two new retinoid drugs, isotretinoin and etretinate, were very effective at preventing new skin cancers in people who had predisposing genetic disorders. After several years of preliminary clinical studies, Kraemer, DiGiovanna, and Peck published a landmark paper in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating that isotretinoin had substantial, effective, skin cancer chemopreventive benefit in patients with XP (New Engl J Med 318:1633–1637, 1988).

This work led to the widespread use of retinoids in patients—including immunosuppressed transplant recipients—who were at high risk for multiple skin cancers. Peck, who left NIH in the 1990s to become the founding director of the Melanoma Center in the Washington Cancer Institute (Washington, D.C.), won several awards in recognition of his discovery of isotretinoin (Accutane) for the treatment of severe, recalcitrant nodulocystic acne and other applications, including the prevention of basal-cell carcinomas.

Peter Steinert came to NCI’s Dermatology Branch in 1973 and in 1990 started the Laboratory of Skin Biology in NIAMS. An international expert in the structural biology of the skin, he did extensive work clarifying keratin intermediate filament assembly and structure, identified novel cell-envelope components, characterized enzymes (transglutaminases) involved in their cross-linking, and elucidated the process of cell-envelope assembly. He died in 2003.

DiGiovanna, in collaboration with the geneticist Sherri Bale, Steinert, and others, led a team to study families with rare inherited disorders of cornification (the formation of a horny layer of skin from squamous epithelial cells). In 1994, DiGiovanna moved to NIAMS as the head of the Dermatology Clinical Research Unit; his group discovered the genes underlying several severe skin disorders including epidermolytic hyperkeratosis and lamellar ichthyosis. In 2000, Bale and molecular biologist John Compton left NIAMS to start a genetic-testing company. DiGiovanna, currently a senior research physician in NCI, continues to work with Kraemer on the clinical, basic, and translational studies of DNA-repair disorders.

Steve Katz as Chief (1980–2001)

Katz, who had come to NIH in 1974 and had started his own laboratory with Ken Hertz and a technician, became Acting Branch Chief in 1977 and permanent chief in 1980. Under Katz’s leadership, the branch started having a greater focus on the skin as an immunological organ. There was an increasing interest in skin immunology worldwide at the time, and Katz was considered a pioneer in the field.

Katz’s “research showed that skin is an important component of the immune system both in its normal function and as a target in immunologically mediated disease,” wrote Benjamin Barkin in a 2016 article in The Dermatologist. In addition, “Dr. Katz and his colleagues have added considerable new knowledge about inherited and acquired blistering skin diseases.” Katz discovered an antigen that is associated with pemphigus vulgaris, an antibody-mediated autoimmune skin disease that results in blisters (J Clin Invest 70:281–288, 1982).

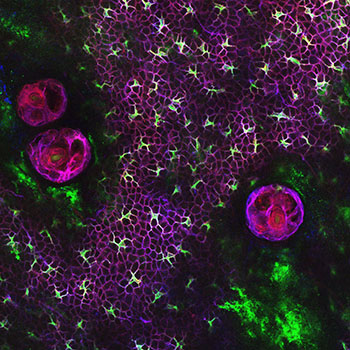

CREDIT: CHRIS NAGAO, NIAMS

Former Dermatology Branch Chiefs Steve Katz and Mark Udey, as well as others in the branch, made important discoveries concerning Langerhans cells, which are dendritic cells of the skin and present in all layers of the epidermis. Shown: Langerhans cells visualized in whole-mount skin. The purple circles are hair follicles.

In addition, Katz did landmark studies on Langerhans cells, which are dendritic cells of the skin and present in all layers of the epidermis. His first stint with the cells was when he and Georg Stingl, then a postdoctoral fellow from Vienna (he later became professor and chair of dermatology at the Medical University of Vienna in Vienna), investigated the immunological functions of surface markers of Langerhans cells. These studies, done in collaboration with David Sachs (now a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School in Boston), led to the new discovery that Langerhans cells could originate from a mobile pool of cells in the bone marrow and likely play an important role in allogeneic graft rejection. (Nature 282:324–326, 1979).

In his long association with the Dermatology Branch, Katz supervised dozens of trainees, many of whom went on to become notable leaders in dermatology around the world. Some luminaries are Tom Lawley, who studied immunologically mediated skin diseases and later became the Dean of Emory University School of Medicine (Atlanta); John Stanley, who described autoantigens in autoimmune blistering diseases and left NIH to lead the Dermatology Department at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (Philadelphia); Kim Yancey, who helped characterize the pathophysiology of autoimmune and inherited blistering diseases and went on to became professor and chair of the Department of Dermatology at the Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) and then at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas); Thomas Darling, who diagnosed and treated people with autoimmune blistering diseases, investigated the molecular basis of these diseases, and subsequently became chair of the Dermatology Branch at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, Maryland); Shinji Shimada, who studied melanoma and is now the president of the University of Yamanashi (Kofu, Japan); Isaac Brownell (NIAMS), who contributed to the development of avelumab, a novel drug to treat Merkel-cell carcinoma; Kevin D. Cooper who did seminal studies on psoriasis (he later became professor and chair of dermatology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio); and Douglas R. Lowy (he was a senior investigator in the Dermatology Branch in 1975–1983 and is now the acting director of NCI) and John Schiller (chief of NCI’s Laboratory of Cellular Oncology), who together won the 2017 Lasker Award for the development of the human papillomavirus vaccine in the 1990s.

In 1995, Katz became the director of NIAMS, but he remained as the Dermatology Branch Chief until 2001, when Mark Udey took over. Katz also continued his own dermatology research until his death in 2018.

“I don’t know anyone who’s had as broad an impact [in the dermatology field] as Steve Katz,” said Udey. “He trained over 45 people” who have gone on to play significant roles in dermatology.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF THOMAS DARLING

Steve Katz (holding plaque) won the 2014 Dermatology Foundation Lifetime Career Educator Award.

Mark Udey as Chief (2001–2017)

The Dermatology Branch, when Mark Udey was chief (2001 to 2017), broadened its range of research to include studies of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and Merkel cells.

Udey, who had been an assistant professor of medicine (dermatology) at Washington University School of Medicine (Saint Louis), was drawn to NIH in 1989 because it was doing research in areas that interested him: skin immunology and Langerhans cells. He became internationally recognized for his work on cutaneous immunophysiology and for his seminal research on the biology of Langerhans cells including the role of epithelial cadherin (which plays a role in cell migration and adhesion) and transforming-growth-factor–beta (which controls cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation) in the cells’ development and localization.

Udey left NIH in 2017 to become a professor in the Department of Medicine (Dermatology) at the Washington University School of Medicine. He has also been the editor of the Journal of Investigative Dermatology since 2017. Udey rose from the position of investigator to senior investigator in 1996 and to branch chief in 2001. Under his leadership, the branch expanded its clinical-research program and broadened its range of research to include studies of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and Merkel cells. The branch also continued to be a training ground for dermatologists. Udey considers one of his major accomplishments to be the recruitment and mentoring of Ed Cowen, Heidi Kong, Isaac Brownell, and Chris Nagao, who are all leaders in NIH’s Dermatology Branch now.

Today’s Dermatology Branch

In 2017, soon after Udey’s departure, the Dermatology Branch moved from NCI to NIAMS. The move made sense, according to NIAMS Scientific Director John O’Shea, because the institute studies skin diseases as well as arthritis and musculoskeletal diseases. Despite the administrative shift, branch scientists didn’t even have to move their labs because they were already adjacent to NIAMS labs in the NIH Clinical Center (Building 10).

CREDIT: BENJAMIN VOISIN, NAGAO LAB, NIAMS

In today’s Dermatology Branch, Chris Nagao’s group has identified hair follicles as the control towers of skin immunity; the follicles guide the localization of skin-resident immune cells and enhance their survival by producing chemokines and cytokines. Shown: Innate lymphoid cells (ILC) that have been guided to the upper hair follicles where they control sebaceous gland (SG) function to tune the microbial balance on skin surface.

Today, the Dermatology Branch is headed by Acting Chief Edward Cowen and continues to conduct clinical and basic investigations of skin biology and researches the etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of skin disease. Research areas of interest include the skin as an immunological organ and the role of tissue-leukocyte-microbiota cross-talk in mediating immunological and structural homeostasis; inflammatory skin diseases in patients and in mouse models; the human microbiome in healthy individuals as well as in patients with atopic dermatitis and primary immunodeficiencies; long-term clinical and laboratory studies and investigator-initiated therapeutic trials in chronic GVHD, neurofibromatosis, and autoinflammatory skin disease; skin stem cells; and cutaneous malignancies including Merkel-cell carcinoma.

Following are highlights of the Branch’s current activities:

Dermatology Consultation Service

Head: Senior Clinician Edward Cowen, M.D., M.H.Sc.

The Dermatology Consultation Service evaluates patients with a variety of rare diseases that have cutaneous manifestations. The service also evaluates and treats patients who experience adverse reactions to experimental therapeutic agents or develop unrelated skin conditions while at the NIH. Dermatology Branch clinical fellows, fellows from other NIH ICs, and visiting dermatology residents from around the country receive training on the service.

Cowen is one of a very few dermatologists in the United States studying cutaneous GVHD. His group performs interventional trials and translational studies and has published extensively on the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD. Among several important findings, he discovered that total-body radiation during conditioning before hematopoietic-cell transplantation poses a risk for the development of a debilitating form of skin thickening caused by GVHD. He also found that adverse reactions to the antifungal agent voriconazole can cause immunosuppressed patients, including patients with GVHD, to develop squamous-cell carcinoma.

Assistant Research Physician Dominique Pichard studies patients with rare diseases such as chronic GVHD and neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1). She is conducting clinical trials in both of these disorders: One is testing the efficacy of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor ruxolitinib as a treatment for epidermal chronic GVHD; the other is testing the efficacy of a systemic mitogen-activated-protein-kinase-kinase (MEK) inhibitor in NF1 cutaneous neurofibromas. She also sees patients on the Dermatology Consult Service.

Cutaneous Development and Carcinogenesis Section

Head: Investigator Isaac Brownell, M.D., Ph.D.

This section studies the regulation of cutaneous stem cells and the molecular pathogenesis of skin cancer. Specifically, the section is investigating the development, maintenance, and malignancies of Merkel cells (neuroendocrine cells in the skin that sense light touch). Merkel-cell carcinoma is a rare and very lethal type of skin cancer.

Brownell oversaw a clinical trial in which immunotherapy was used to target cancer cells in patients with Merkel-cell carcinoma. The trial was successful and resulted in the 2017 FDA approval of avelumab to treat this cancer. His team collaborates with the National Center for Advancing Translational Science to do drug-discovery studies for this disease and plans to test one of the drugs in a clinical trial in collaboration with the NCI Rare Tumors Initiative and AstraZeneca, which manufactures a nanoparticle version of this drug.

Cutaneous Microbiome and Inflammation Section

Head: Investigator Heidi H. Kong, M.D., M.H.Sc.

The section studies the skin microbiome—in both healthy individuals and patients with skin diseases—with the goal of expanding the understanding of host-microbe interactions. The Kong group has examined the role of microbes in atopic dermatitis and other eczematous skin diseases. The group has focused on the significant bacterial shifts in the skin of patients with atopic dermatitis as well as in patients with primary immunodeficiency syndromes who have eczematous skin conditions. Current work has expanded to include investigations into human-skin fungi and viruses.

Kong is collaborating with NCI investigators to look at the skin microbiome of cancer patients who are undergoing treatment with immunotherapies. She also works closely with NCI and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) researchers to study and care for patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) immunodeficiency who are undergoing stem-cell transplants. The syndrome is a rare immune disorder that causes immune cells to malfunction; patients suffer from recurrent viral infections of the skin and respiratory system. People with DOCK8 immunodeficiency syndrome also typically have allergies, asthma, and an increased risk for some types of cancer.

Since 2007, Kong has partnered with Julie Segre (National Human Genome Research Institute) to perform many large-scale DNA-sequencing skin-microbiome studies. Their analyses have shown that human microbiota varies by specific regions of the skin surface and among individuals.

Cutaneous Leucocyte Biology Section

Head: Stadtman Investigator Keisuke (Chris) Nagao, M.D., Ph.D.

Nagao collaborates with Kong and investigators in NIAID to understand the human-disease pathology that underlies inflammation and susceptibilities to certain microbial agents. In particular, Nagao focuses on patients with severe drug hypersensitivities (life-threatening reactions to drugs, which have skin and multiorgan manifestations) and monogenic diseases that manifest as atopic skin inflammation. He receives cross-support for his work from other ICs in the form of collaborations with investigators in the NCI, NIAID, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and the National Institute on Aging.The section is exploring the mutual cross-talk that occurs among the skin epithelium, the microbiota, and the immune cells that are involved in maintaining immunological and microbial homeostasis in skin. In particular, Nagao’s group has identified hair follicles as the control towers of skin immunity; the follicles guide the localization of skin-resident immune cells and enhance their survival by producing chemokines and cytokines. In turn, the immune cells help shape the function of the skin barrier. The group has established that such cross-talk is crucial in regulating the balance of the skin microbiota during homeostasis and that imbalance, or dysbiosis, of the microbiota drives inflammation in atopic dermatitis.

Training Continues to Be Important

Dermatology Grand Rounds: One of the highlights of the Dermatology Branch is the twice-a-month Dermatology Clinical Grand Rounds that highlight unusual dermatology cases. The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology features these “Grand Rounds at the NIH” quarterly and highlights interesting cases evaluated by NIAMS’s Dermatology Consultation Service.

Clinical Fellowship: For over 20 years, the Dermatology Branch has been offering advanced training in clinical and translational research for dermatologists after they complete their residency. Now known as the Scholars in Translation Research in NIAMS, this two- to three-year program has produced several notable alumni. Cowen, Kong, and Pichard have themselves been fellows of the program.

NIH-Duke Master’s Program in Clinical Research: Clinical Research Fellows in the Dermatology Branch may choose to also enroll of this formal degree program in collaboration with Duke University.

NIH Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP): Medical students in their third or fourth year who are enrolled in the MRSP can choose a yearlong project covering basic, clinical, or translational research at the branch.

Other Dermatology Research at NIH

In addition to the collaborators mentioned above, other researchers outside the NIAMS Dermatology Branch are doing skin-related research, too. The following list is by no means comprehensive.

Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Nehal Mehta (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) and his group used a type of computed tomography (CT) imaging to find a strong link between the extent of psoriatic skin disease and the degree of vascular inflammation. Using coronary CT angiography, his team showed that inflammation associated with the severity of psoriatic skin disease directly relates to plaque in coronary arteries. Most recently, Mehta’s team earned an NIH Director’s Award for completing a series of preliminary studies in humans that found that treating skin disease in psoriasis improves both vascular inflammation and coronary plaque.

Kenneth Kraemer and John DiGiovanna (both in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics), mentioned earlier, study XP and the clinical, basic, and translational studies of DNA-repair disorders.

Maria Morasso (NIAMS Laboratory of Skin Biology) has long-standing research investigating the mechanisms that regulate epidermal development and differentiation. In a recent collaboration with J. Silvio Gutkind (who was at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and has since left NIH), her group identified physiological and molecular determinants that explain why wounds inside the mouth heal quicker than ones on the skin.

Yasmine Belkaid (NIAID) explores the mechanisms controlling host-microbe interactions at barrier sites such as the skin and the gut.

Stuart H. Yuspa (NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics) uses a mouse model to investigate the pathogenesis of squamous-cell carcinoma (the second-most-common form of skin cancer). His findings reflect that squamous-cell carcinoma develops in multiple internal-lining epithelia and show how cancer cells interact with the microenvironment.

To read the oral-history interview with Steve Katz, go to https://history.nih.gov/archives/downloads/stephenkatzinterview6182018.pdf

Stephen Katz inspired many. Read some remembrances by former colleagues and postdocs.

This page was last updated on Monday, April 4, 2022