Alternative Therapy Relieves Immunotherapy’s Neurological Consequences

Case Studies Highlight New Way to Treat Common Side Effect

IRP researchers’ experiences using CAR-T cell immunotherapy to treat children with leukemia point towards a better way to manage one of the therapy’s most serious side effects.

New medical treatments nearly always come packaged with new side effects. CAR-T cell therapy, a game-changing ‘immunotherapy’ for cancer, is no exception. However, a set of case studies reported by IRP researchers could help physicians better contend with one of the therapy’s most worrisome complications.1

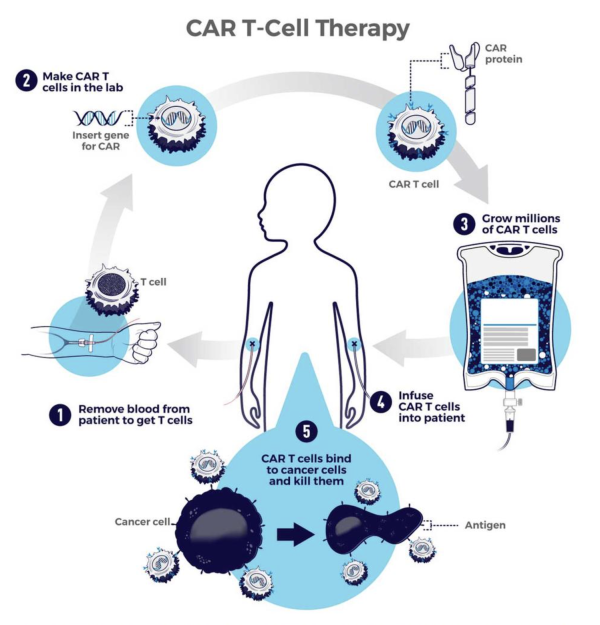

CAR-T cell therapy involves collecting immune cells called T cells from a patient's blood, genetically modifying them to turn them into cancer killers, growing millions of the modified cells in the lab, and then returning the cancer-seeking missiles to the patient’s body. As promising as the approach is for eliminating cancer, the first CAR-T cell therapy was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only a bit more than six years ago, so clinicians are still figuring out the best ways to manage its less desirable effects.

“With the advent of this new immunotherapy, we also started to see new side effects and a different toxicity profile than we were used to with traditional chemotherapy or radiation therapy,” explains Haneen Shalabi, D.O., the new study’s first author and a former assistant research physician in NIH’s Pediatric Oncology Branch who works alongside the study’s senior author, IRP Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Nirali Shah, M.D.

This diagram shows the steps involved in CAR-T cell therapy.

In fact, medical professionals only settled on standardized definitions for two common side effects of CAR-T cell therapy in 2019. The first, called cytokine release syndrome (CRS), occurs when the immune system overreacts after CAR-T cells are introduced into a patient’s body, leading to flu-like symptoms that can range from mild to life-threatening. The other, called immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), specifically causes neurological symptoms that similarly range in severity. The two conditions are thought to be related because patients almost never develop ICANS unless they get CRS first, and the more severe their CRS, the more likely they are to subsequently develop ICANS.

When ICANS produces serious symptoms, physicians give patients infusions of corticosteroids, a class of medication that broadly suppresses the immune system. However, pumping patients full of corticosteroids doesn’t always work and can come with troubling consequences of its own.

“Corticosteroids are the treatment of choice, but if patients continue to get worse, really the only thing we have is to continue to drive up the steroid dose or change the steroid we’re giving from one version to another,” Dr. Shalabi says.

“When someone has either persistent or worsening ICANS, being on high doses of steroids for a long time also has severe effects associated with it,” adds Dr. Shah. “It’s a systemic therapy you’re giving for a toxicity where ideally you’d like to be more directed.”

As a result, a few research programs studying CAR-T cell therapy, including Dr. Shah’s, have adopted another approach to treating ICANS. Instead of introducing corticosteroids into patients’ blood, they inject a particular steroid called hydrocortisone into the ‘intrathecal’ space where cerebrospinal fluid flows around the spinal cord, enabling the treatment to more directly target the brain rather than circulate around the entire body. The treatment does require a lumbar puncture, which involves sticking a hollow needle into the space surrounding the spinal cord; however, that procedure is already part of standard therapy for children with B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), the most commonly diagnosed form of childhood leukemia and the main pediatric cancer for which CAR T-cells are used as a treatment.

A patient receives a lumbar puncture, the procedure necessary to deliver medications directly into the cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the spinal cord.

The new study from Dr. Shah’s research group specifically details observations from two clinical trials of a new type of CAR-T cell therapy involving 79 children with B-ALL. Seven patients developed severe ICANS after receiving an infusion of CAR-T cells, and five of them were eventually given a single dose of intrathecal hydrocortisone after systemic infusions of corticosteroids did not alleviate their symptoms. Remarkably, all five of those patients saw their symptoms retreat within the next 24 hours.

“This is just a collection of our experiences, but putting together five cases shows people that it wasn’t just a one-off,” Dr. Shalabi says. “We had five patients who had dramatic improvement in symptoms within hours. It was quite striking.”

The IRP researchers also reported some interesting observations from the routine set of tests they use to evaluate and monitor patients enrolled in their studies. Before patients received the CAR-T cell therapy, the amount of protein molecules in the cerebrospinal fluid was higher in those who would later experience both CRS and ICANS than in patients who only came down with CRS. Patients who would go on to develop both CRS and ICANS also had lower blood levels of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory molecule produced by the immune system, compared to patients who only developed CRS. While these findings are preliminary due to the small number of patients in the study who experienced CRS and ICANS, they nonetheless hint at the causes of the two conditions and ways physicians might predict which patients will experience them.

Dr. Haneen Shalabi (left) and Dr. Nirali Shah (right)

“There’s just not a lot of data out there, so whatever information we can share with the community is useful,” Dr. Shalabi says. “With every case series, there’s this big asterisk because of the small sample size, so this could be due to chance, but it’s also something that we should continue to look for as we do larger studies.”

The more certain contribution of Dr. Shalabi and Dr. Shah’s study, though, is to demonstrate that intrathecal delivery of hydrocortisone is a safe and effective alternative treatment for ICANS. After more than a decade studying CAR-T cell therapy at NIH and repeatedly seeing patients with ICANS benefit from intrathecal hydrocortisone, Dr. Shah is convinced that the treatment should be a weapon in every doctor’s arsenal to combat severe ICANS and even potentially to prevent mild ICANS symptoms from getting worse.

“You see something like that happen right in front of your eyes and you become a believer,” she says. “There’s no way around it. I think you kind of have to see it to believe it. We haven’t had a negative experience with it, and so we do hope that more people start to think about this approach.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Shalabi H, Harrison C, Yates B, Calvo KR, Lee DW, Shah NN. Intrathecal hydrocortisone for treatment of children and young adults with CAR T-cell immune-effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2024 Jan;71(1):e30741. doi: 10.1002/pbc.30741.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Friday, February 23, 2024