Bringing Out the Big Guns Against Blood Cancer

IRP Research Shows Benefits of More Intensive Treatments for Certain Patients

IRP researchers are working to improve outcomes for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by developing clinical tools that can help doctors make more informed decisions about the treatments their patients receive.

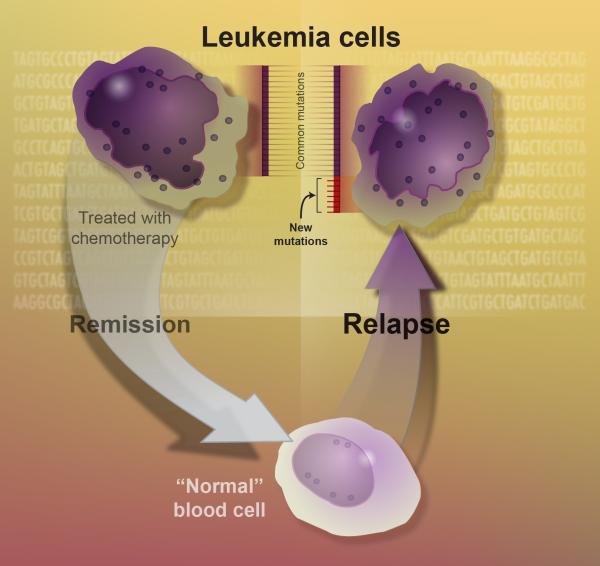

Fate can be cruel, especially when it comes to a rare, highly fatal blood cancer called acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Even when months of intensive chemotherapy appear to cause a complete remission of the disease — meaning doctors cannot detect any remaining cancer cells in a patient’s body — roughly half of those patients see the cancer return within two years, or even as soon as six months. Sadly, most of them don’t survive their second bout with the disease.

As a medical student, IRP senior investigator Christopher Hourigan, M.D., D.Phil., thought this outcome was unfair. More than that, he thought it indicated that the standard ways doctors determined if an AML patient was in remission were inadequate, and that remission might not even be the right goal. That’s why he has focused his career on finding ways to detect, prevent, and treat AML recurrence, known in his field as ‘relapse’.

“I was a scientist before I became a doctor, and it was really eye-opening to me, when I started to practice medicine, how difficult some of the treatment decisions were and how limited the information available was to inform those decisions,” Dr. Hourigan says.

A central part of Dr. Hourigan’s work in the Laboratory of Myeloid Malignancies at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) is focused on developing highly sensitive and specific diagnostic tools to detect residual leukemia cells left lurking post-treatment in patients’ bone marrow, which is the source for both normal blood cells and aberrant leukemia cells. AML patients whose disease is in remission are given bone marrow transplants to wipe out any remaining cancer cells by replacing diseased bone marrow with healthy marrow. However, the procedure’s success rate is akin to a coin flip. Dr. Hourigan and his research team want to understand why the procedure has such a high failure rate and, more importantly, come up with ways to identify patients who are at higher risk for post-transplant relapse and to do something to improve those patients’ chances of survival.

AML relapse occurs when cancerous leukemia cells begin popping up in a patient’s body again even after chemotherapy had seemingly eliminated all the cancer cells in his or her body, a state known as remission.

Bone marrow transplants require the use of ‘preparative conditioning therapy’ to destroy both cancer cells and healthy blood cells developing in the bone marrow. Healthy donor bone marrow is then infused into a patient’s bones to replace his or her old bone marrow. Ideally, the healthy, disease-fighting white blood cells that the new bone marrow produces will be able to keep the leukemia from coming back.

“It’s incredible,” Dr. Hourigan says. “You are rebooting — it’s like hitting ‘Ctrl/Alt/Delete’ on the computer. For many patients with AML, this is the only route to cure. But it doesn’t always work.”

To figure out the reason for the high failure rate, Dr. Hourigan partnered up with researchers from the NIH-funded Bone Marrow Transplant Controlled Clinical Trial Network, who had launched a phase III randomized clinical trial in 2011 comparing the outcomes of AML patients in remission who underwent highly intensive or less intensive preparative therapy as part of their bone marrow transplants. The less intensive approaches are typically used to reduce side effects and are particularly important for people who are older or whose overall health is too fragile to withstand higher-intensity treatments.

Unfortunately, the data quickly showed that less intensive transplants were significantly less successful at staving off relapse. In fact, the difference was so stark that the study was stopped early. Still, Dr. Hourigan and his research team saw the study as a golden opportunity to search for biological markers related to a higher risk of relapse in AML patients.

“To us, it seemed like the perfect trial to ask that question,” Dr. Hourigan says. “Our hypothesis was that the outcome would be bad mainly for those patients with trace levels of leukemia left after chemotherapy who then received a reduced-intensity transplant. It’s pretty simple, but answering the question in a definitive way requires a large randomized clinical trial with hundreds of patients.”

In this video, Dr. Hourigan discusses how his team developed genomic tools to detect low levels of cancer in patients with AML.

Dr. Hourigan’s team used very sensitive genomic sequencing and computational techniques to find the trace levels of leftover leukemia in stored blood samples collected from the patients who participated in the Network’s study after remission but before their transplants. As expected, the IRP researchers found that if patients showed signs of lingering leukemia cells before a less intensive transplant, they were more likely to relapse than those who received intensive transplants. On the other hand, patients with no remaining signs of AML in their blood before a less intensive transplant had the same low chances of relapse as patients who had received an intensive transplant. This suggests that doctors could potentially help keep more patients disease-free for longer by testing them for signs of remaining cancer and using the results to inform treatment decisions about the intensity of transplant a particular patient requires.

“I think there are two implications from the findings,” Dr. Hourigan says. “One is that we probably shouldn’t use reduced intensity transplants, when possible, in people who have detectable residual leukemia. The other point that I think really sparked people’s imagination is the idea that still having measurable residual disease after initial treatment is not just fate. There’s a tangible thing we as doctors can do to improve the outcomes.”

Dr. Hourigan (middle) with two members of his team — Staff Scientist Laura Dillon (left) and statistician Gege Gui (right) — at the 2022 meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), where he presented the results of the Pre-MEASURE study.

Only three years after publishing those findings in 2019, Dr. Hourigan’s discoveries are being included in clinical guidelines for treating AML. Nevertheless, more work remains to be done to improve the outcomes of AML patients. Since publishing that study, Dr. Hourigan’s lab has been hard at work determining if using genomic tests capable of detecting tiny numbers of lingering leukemia cells can improve the clinical standard of care for AML. The first part of this effort, called Pre-MEASURE, tested banked pre-transplant blood samples from 1,075 AML patients in remission and found that signs of those residual cancer cells were strongly associated with later relapse. Dr. Hourigan’s lab and its collaborators are now beginning a larger, multi-center study, called MEASURE, to see if such testing can be integrated into clinical practice nationally.

“I think there has been incredible value for our intramural laboratory to collaborate with clinical networks outside NIH to add value to the efforts they are already doing by adding an initial layer of scientific investigation,” Dr. Hourigan says. “I think that, for my program, specifically, this is a model of how we’re going to go forward. It’s a win-win for everyone. It's great for us in that we have access to relevant, clinically annotated, important samples with meaningful outcomes, and it’s great for the bone marrow transplant community because they get extra value from the clinical work and trials that have already been done. Most importantly, it is better for patients who will ultimately have more accurate information on the status of their cancer after initial treatment and personalized, evidence-based advice on what best to do next.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023