Therapeutic Strategy Protects Heart From Diabetic Damage

Mouse Study Points to Approach for Preventing Diabetes-Related Heart Failure

High blood sugar can damage the heart in people with diabetes, but IRP researchers have identified a promising strategy to stop this from happening.

Our cells love to lap up sugar from our blood, but as is often the case, too much of a good thing can cause problems. In people with diabetes, chronically high blood sugar can harm organs, including the heart. In an effort to combat this life-threatening problem, IRP researchers demonstrated in mice that activating a specific biological pathway in heart cells can reduce diabetes’ damaging effects on the vital organ.1

In recent years, more and more Americans have gained first-hand experience with chemicals called cannabinoids, which are responsible for the ‘high’ and other effects that have made marijuana so popular. Both the cannabinoids in marijuana, such as THC, and those produced by the human body itself exert their effects by interacting with two types of receptors. Cannabanoid type 1 (CB1) receptors are highly prevalent in the brain, making them largely responsible for marijuana’s psychological effects, although they are also found in other parts of the body as well. Cannabinoid type 2 (CB2) receptors, on the other hand, do most of their work outside the brain, including in certain immune system cells. Their numbers also increase in the lining of the heart and blood vessels when the cardiovascular system is damaged.

The cannabinoids in marijuana have a wide array of effects on the body, but the body also produces its own cannabinoids as well.

The distribution of CB2 receptors in our cells — particularly the lower levels in the brain — make it an attractive target for researchers looking to leverage the body’s native cannabinoid system for therapeutic reasons without triggering psychological changes or other unwanted side effects. IRP senior investigator Pal Pacher, M.D., Ph.D., for instance, is interested in whether activating CB2 receptors can reduce the damaging effects that chronically high blood sugar levels have on the heart in people with diabetes, which lead to a dangerous condition called diabetic cardiomyopathy.

“Most cardiomyopathies, with progression, eventually lead to heart failure when the heart’s compensatory mechanisms are exhausted,” Dr. Pacher says. “Most currently available treatments for diabetic cardiomyopathy focus on the treatment of diabetes and heart failure when it develops. No targeted treatments for diabetic cardiomyopathy are currently available.”

Past studies, including research performed in Dr. Pacher’s lab, have suggested that activating CB2 receptors can help alleviate the damage wrought by a variety of conditions, including heart attacks, strokes, and a form of cardiomyopathy caused by liver damage.2 To assess whether the same approach might help protect the hearts of people with diabetes, Dr. Pacher’s team treated mouse models of type 1 diabetes, as well as healthy mice, with a drug called JWH-133 that selectively activates CB2 receptors.

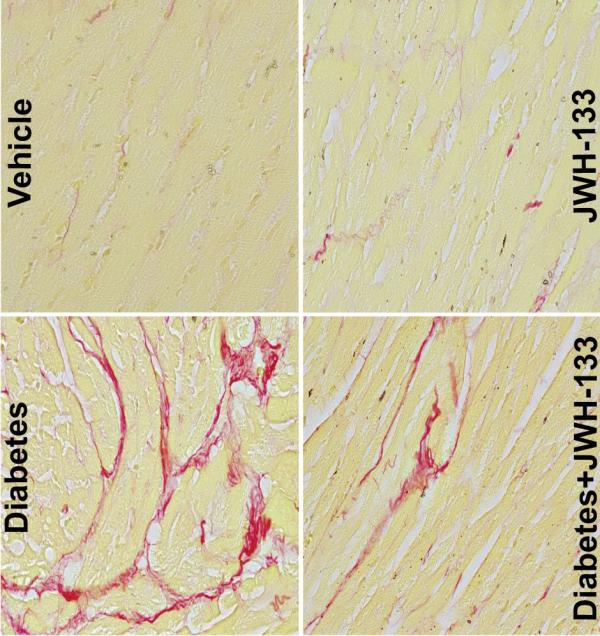

These images from the study show increased amounts of collagen (red) in the hearts of mice with type 1 diabetes. JWH-133 treatment decreased the amount of collagen in the diabetic animals’ hearts.

As expected, after 12 weeks of chronically elevated blood sugar levels, the diabetic mice had significantly impaired heart function and their heart tissue showed increased signs of damaging oxidative stress and inflammation. In addition, the researchers found that the diabetic animals experienced accelerated death of the cells that help the heart beat. Finally, the hearts of the diabetic mice underwent extensive ‘cardiac remodeling,’ during which changes to the structure of the heart impair its function, in part by replacing cardiac muscle cells with a stiff material called collagen.

“Cardiac remodeling means the structure and function of the heart is changing,” Dr. Pacher explains. “You have more stiff connective tissues, so you are losing contractile function and you are making the heart more rigid. It will be like if you imagine a kind of rubber ball that gets stiffer and stiffer, and you will not be able to compress it. It will be more difficult for the heart to pump blood.”

On the other hand, the hearts of diabetic mice that received daily injections of JWH-133 during all but the last week of that 12-week timespan ended up in much better shape. Those animals’ hearts pumped more effectively and experienced less inflammation, oxidative stress, cell death, and remodeling. Meanwhile, diabetic mice that lacked the gene that produces CB2 receptors showed even worse deterioration on all these measures compared to their genetically normal counterparts. This provided strong evidence that CB2 receptors play a role in protecting organs like the heart from damage.

Overall, the results bolster Dr. Pacher’s belief that selectively activating CB2 receptors could be a boon to the health of people with type 1 diabetes. However, don’t go out to your local cannabis dispensary looking to improve the health of your heart, as the cannabinoids in marijuana activate both CB2 receptors and CB1 receptors, the latter of which can actually promote inflammation and other unwanted physiological changes in the cardiovascular system.

Dr. Pal Pacher

Moreover, while the study showed that CB2 receptor activation could protect the heart, the researchers did not test whether activating CB2 receptors would have any benefits for a heart that had already experienced significant deterioration. In addition to answering that question and helping to develop even more selective and potent CB2 receptor activators, Dr. Pacher’s team is working on a way to detect where and when CB2 receptors are most abundant in the body. This would help scientists design more targeted treatments and learn more about when in the course of disease it might be most effective to administer them.

“If you cannot detect reliably in diseased tissues that CB2 is increased, and in which cell types, then it is extremely difficult to do target validation,” Dr. Pacher says. “Without target validation, in clinical trials, you are kind of doing everything blindly. If you have, say, an inflammatory disease in certain tissues, it is very important to see during what phase of inflammation you have the most CB2 or which cell types have CB2 because you may want to target the early phase of inflammation rather than the late phase. You can actually achieve the opposite result if you don’t target at the right time.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Rajesh M, Mukhopadhyay P, Bátkai S, Arif M, Varga ZV, Mátyás C, Paloczi J, Lehocki A, Haskó G, Pacher P. Cannabinoid receptor 2 activation alleviates diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction, inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. Geroscience. 2022 Apr 22. doi: 10.1007/s11357-022-00565-9.

[2] Matyas C, Erdelyi K, Trojnar E, Zhao S, Varga ZV, Paloczi J, Mukhopadhyay P, Nemeth BT, Haskó G, Cinar R, Rodrigues RM, Ahmed YA, Gao B, Pacher P. Interplay of Liver-Heart Inflammatory Axis and Cannabinoid 2 Receptor Signaling in an Experimental Model of Hepatic Cardiomyopathy. Hepatology. 2022 Apr;71(4):1391-1407. doi: 10.1002/hep.30916.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023