Extreme Obesity Shaves Years Off Life Expectancy

Four Questions with Dr. Cari Kitahara

IRP research shows that excess weight dramatically shortens life expectancy, but — encouragingly — even a small amount of intentional weight loss can significantly reduce the risk of death and disease for people with obesity. Photo source: UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity

As happens with every new year, many people around the world woke up on January 1 committed to improving their health through eating well and exercising. These lifestyle changes have the potential to significantly improve the well-being of the 32 percent of American adults who are overweight and the 40 percent who are obese. Due to the staggering number of individuals struggling with obesity, as well as its serious health consequences, the condition has long been a main priority for researchers at the NIH. As a result of this focus, investigators have made significant strides in identifying biological signals that trigger hunger, understanding genetic influences that play a role in weight gain, and uncovering environmental and behavioral factors that influence obesity.

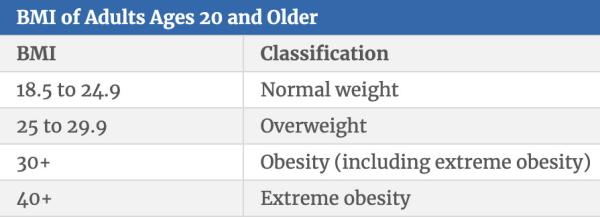

A 2014 study led by IRP investigator Cari Kitahara, Ph.D., utilized data from the 20 different studies included in the Body Mass Index (BMI) and All-Cause Mortality Pooling Project of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cohort Consortium to examine the relationship between BMI and cause-specific mortality rates in people with extreme obesity. BMI is the ratio of an individual’s height to his or her weight. Typically, a BMI of 18.5-24.9 represents a healthy weight, while an individual with extreme obesity has a BMI of 40 or more and is usually at least 100 pounds over his or her ideal body weight. Through their research, Dr. Kitahara and her colleagues made the stunning discovery that extreme obesity can shorten lifespan by as much as 14 years.

In honor of Healthy Weight Week this week, I connected with Dr. Kitahara to discuss her experience in studying obesity, her passion for learning more about the condition, and her team’s continuing efforts to build on its prior findings.

What prompted you to conduct this study?

“My research was inspired by a 2010 study within the BMI and All-Cause Mortality Pooling Project spearheaded by my mentor and advisor, Dr. Amy Berrington de González. That study used data collected from more than a million white adults to better quantify how being overweight or obese affects all-cause mortality and to identify the BMI associated with the lowest risk of death. Through this research, the team identified that death rates among never-smokers without pre-existing heart disease or cancer was lowest for those with a BMI of 22.5 to 24.9, and that the risk of death rose 31 percent for every fiv-unit increase in BMI up to a BMI of 49.9, the highest BMI included in the study. Participants whose BMIs were between 40 and 49.9 were more than twice as likely to die during the study period than those whose BMI was in the optimal range of 22.5 to 24.9.

“Around the time that study was published, other studies were released showing that extreme obesity in adults had been rapidly increasing around the world, especially in the United States. Connecting the dots between the results from these studies — the climbing rate of obesity and the significant impact of obesity on mortality rates — sparked my desire to better understand the health outlook of these individuals.

This table shows the BMI values associated with a healthy weight, overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity.

“This curiosity led me to initiate a research project by building off the results from the BMI and All-Cause Mortality Pooling Project. My team looked at not only the participants included in the 2010 study, which was limited to white individuals, but expanded the analysis to include non-white individuals and individuals with BMI values of 50 to 59.9. In doing so, we found that an individual’s risk of death continued to increase at the high end of that BMI range. Specifically, we found that BMIs from 40 to 44 were associated with 6.5 years of life lost, but this increased to 8.9 for BMIs from 45 to 49, 9.8 for BMIs from 50 to 54, and 13.7 for BMIs from 55 to 59. This suggests that any amount of intentional weight loss may have major health benefits for individuals who are extremely overweight or obese.

“While we were able to uncover some truly interesting insights about the risk of mortality in obese individuals, we also wanted to learn more about the specific factors that drive that elevated risk. When we looked into the causes of death, we discovered that when comparing the obese group in the study, including individuals with BMI values between 40 and 59, to the healthy-weight group with BMI values between 18.5 and 25, there is a clear pattern of increased risk in every major cause of death linked to metabolic disorders like diabetes and hypertension. These major causes of death include heart disease, cancer, diabetes, kidney diseases, and liver diseases. However, our findings also suggest that, for individuals who are considered extremely obese, losing any amount of weight may help to reduce these risks and increase life expectancy.”

How did the research conducted by the NCI aid in your team’s research?

“The NCI Cohort Consortium is an extensive international network of investigators that has allowed researchers to pull together a large amount of data from diverse study populations to investigate important questions of public health concern, including the potential health risks associated with excess body weight. Our study of extreme obesity and mortality builds upon a major early initiative within the NCI Cohort Consortium, the BMI and All-Cause Mortality Pooling Project, which was a major effort to combine data from participants from more than 20 large cohort studies.”

Dr. Cari Kitahara

What role did collaboration play in your study?

“This research truly could not have been completed without collaboration with others at the NCI. Collaboration was integral from the start and has always been key for my group. At the time, my division had a team called the Obesity Action Group that included myself, Dr. Berrington de González, Steven Moore, Patricia Hartge, and Yikyung Park. We got together regularly to discuss major issues in the realms of obesity, physical activity, and health and brainstormed ways to address major issues of current public health concern. It was exciting to be a part of that group and to see what new ideas we could come up with when we put our heads together.

“From a big picture standpoint, Dr. Berrington de González, Dr. Hartge, and others were instrumental in establishing some of the earlier collaborations within the NCI Cohort Consortium and for driving the original research priorities and objectives. Numerous important studies have resulted from these efforts. Specific to our study of extreme obesity and mortality, each team member brought valuable information that allowed us to successfully build off of previous research within the Consortium. In addition to contributing original data for this effort, many of our collaborators had extensive expertise on the subject of obesity and the impact it has on overall health, which allowed for rich discussions on the biological mechanisms that link obesity with death due to chronic diseases like cancer and heart disease. These mechanisms include metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, that are more likely to occur and become increasingly severe with greater levels of excess weight. Another important contribution was Dr. Moore’s idea to convert the relative risk estimates from our study to lost years of life, which ultimately led to the conclusion that the difference in life expectancy between individuals with extreme obesity versus those in the healthy weight range was similar to the difference between current and never smokers.

“All-in-all, it was a tremendous team effort from a fantastic group of researchers committed to chronic disease prevention. Being a part of the NIH helped to provide more direct access to the data and collaborative opportunities available through the NCI Cohort Consortium, which were essential for addressing our research question.”

What impact has this research had on the field and how are you planning to build on it in the future?

“This research highlighted the fact that the number of people with extreme obesity is increasing and that this level of obesity is associated with major adverse health consequences and substantial reductions in life expectancy. On the other hand, these findings are also encouraging because they suggest that losing even a small amount of weight may help individuals who are extremely obese to live longer and reduce their risk of major chronic diseases.

“Obesity is a major public health issue and we need to take steps to not only prevent obesity, but also to support individuals already living with the condition by continuing to study the disease and its connection to other serious health issues. Researchers in my group are continuing to uncover health impacts associated with high levels of obesity, such as the increased likelihood of dying at an early age from major chronic diseases like heart disease, specific types of cancers, diabetes, liver disease, and kidney disease, and to identify racial/ethnic differences in these relationships. Researching these specific areas is important because these studies will help to motivate public health and clinical interventions designed to combat the adverse effects of obesity.”

Head over to our Accomplishments page for more information on Dr. Kitahara’s research, and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024