The Heartache of Discrimination

Allana T. Forde Unpacks Racial Disparities in Heart Health

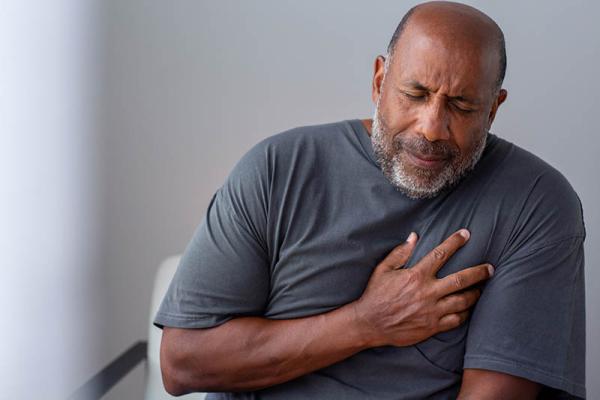

NIH Intramural researchers are investigating the links between discrimination and the heightened risk for cardiovascular disease in Black Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups.

Discrimination comes in many forms, and people experience it and cope with it in different ways. The accumulation of stress arising from discrimination can lead to wear and tear on the body in a process called ‘weathering’,1 which ultimately harms cardiovascular health. This is one of the key reasons Black Americans have a higher rate of cardiovascular disease than all other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. and are much more likely to die from cardiovascular conditions than other racial and ethnic groups.

NIH Stadtman Investigator Allana T. Forde, Ph.D., M.P.H. hopes to reduce these startling health disparities by examining how psychosocial stressors, including discrimination, affect the cardiovascular health of subgroups of the Black population, including Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Latino, and African American individuals. She also endeavors to identify the protective and adaptive factors that impact the relationship between discrimination and cardiovascular health. In honor of American Heart Month, I spoke with Dr. Forde about her research on discrimination and cardiovascular health in Black Americans, as well as how her research might improve cardiovascular health and inform cardiovascular disease prevention strategies.

“Black adults in the U.S. continue to be disproportionately affected by cardiovascular disease, as well as by its risk factors, including high blood pressure, which is a major contributor to heart disease and stroke,” says Dr. Forde. “Therefore, it is imperative to identify the drivers of these conditions in this population.”

Dr. Forde uses the tools of epidemiology — the study of the distribution and determinants of disease in humans — to understand the role of discrimination in cardiovascular health. For example, she has leveraged data from the Jackson Heart Study to examine whether experiences of discrimination were associated with the development of high blood pressure among African American adults living in Jackson, Mississippi. 2

That study used two discrimination scales: one that measures instances of ‘everyday discrimination,’ which she describes as “daily hassles such as being treated with less respect or less courtesy,” and another scale that measures ‘lifetime discrimination’, which includes more severe forms of discrimination like being unfairly denied a loan or housing. She found a marked difference between how everyday and lifetime discrimination affected blood pressure over time, with the latter having a noticeably worse effect.

Dr. Forde’s research shows that discrimination that threatens a person’s livelihood, like being denied a loan or job, is particularly harmful to health.

Next, to assess whether those findings applied to a more geographically and racially diverse population, Dr. Forde repeated her analyses using data from the NIH-funded Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).3 That analysis of data from Black Americans produced the same results as those from her research using Jackson Heart Study participants.

Dr. Forde and her colleagues subsequently expanded on those two studies by examining the impact of discrimination on deaths due to cardiovascular disease over an 18-year period among Black adults who participated in MESA.4 Like her studies on discrimination and high blood pressure, experiences of lifetime discrimination increased the risks that Black adults would die from complications related to cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Forde’s motivation to pursue that research traces back to her time conducting research in Barbados, an island in the West Indies, and at Harlem Hospital in New York City. Based on those experiences, it was clear to her that the perceptions and health effects of discrimination can differ greatly among Black individuals and subgroups of the Black population.

“How people interpret discriminatory experiences is not the same, so that may also impact whether or not someone develops high blood pressure or any other cardiovascular health outcome,” Dr. Forde says. “Black people are very different in many ways — whether you are U.S.-born or foreign-born, whether you belong to a specific heritage group, whether you are first- or second-generation — but there is just not enough research on this subject. That is what really influenced me to research these populations.”

Dr. Allana T. Forde

Those early career experiences contributed to her research focus, but it was her personal experiences that were the most influential in shaping her work. As the daughter of immigrants from Guyana in South America, she did not learn about discrimination and racism from her parents because they perceived the social challenges they faced in the U.S. as stemming more from cultural differences than from racial animus. In fact, when her grandfather first came to the U.S., he visited the segregated South and sat at a “Whites only” lunch counter, apparently unaware of the Jim Crow laws separating white and Black Americans and the often painful consequences of violating them.

“He had no idea; it was not his culture,” she says. “That made me think he was protected from that discrimination all of his life until that moment, and even in that moment, I do not think he fully grasped the big picture of what racism in the U.S. was.”

The next step in Dr. Forde’s research is to investigate the different discrimination experiences within and across subgroups of the Black population. She notes that the scales used in major studies to measure ‘everyday’ and ‘lifetime’ discrimination may not capture the entire picture. She is particularly curious about whether different subgroups of the Black population perceive discrimination differently, which may or may not be evident based on their responses to those questions.

Ultimately, alongside the long-term goals of pursuing racial equity and eliminating discrimination, Dr. Forde hopes that knowing more about how people perceive and react to discrimination can lead to interventions that sever the link between discrimination and adverse cardiovascular health outcomes.

“If we can measure discrimination, we can measure how discrimination impacts health,” she says. “Eliminating discrimination at all levels in the U.S. is challenging and will take time, so the first step is to raise awareness of the negative effects of discrimination on health.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Forde AT, Crookes DM, Suglia SF, Demmer RT. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2019 May;33:1-18.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011. Epub 2019 Mar 19. PMID: 30987864; PMCID: PMC10676285.

[2] Forde AT, Sims M, Muntner P, Lewis T, Onwuka A, Moore K, Diez Roux AV. Discrimination and Hypertension Risk Among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):715-723. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215998.

[3] Forde AT, Lewis TT, Kershaw KN, Bellamy SL, Diez Roux AV. Perceived Discrimination and Hypertension Risk Among Participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(5):e019541. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019541.

[4] Lawrence WR, Jones GS, Johnson JA, Ferrell KP, Johnson JN, Shiels MS, Diez Roux AV, Forde AT. Discrimination Experiences and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2023 Apr;16(4):e009697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.122.009697. Epub 2023 Apr 5. PMID: 37017086; PMCID: PMC10106108.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, February 21, 2024