IRP’s Gary Gibbons and Eliseo Pérez-Stable Receive Government Award for COVID-19 Response

Pair Leads Public Health Efforts Focused on Underserved Communities

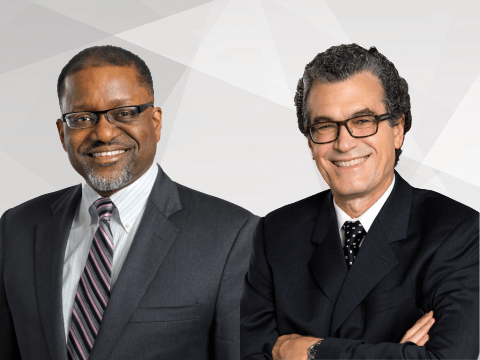

Dr. Gary Gibbons (left) and Dr. Eliseo Pérez-Stable (right) received a special award from the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals for their work on connecting underserved communities to COVID-19 testing, vaccines, and clinical trials.

In the spring of 2020, as the U.S. government implemented public health measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic, it quickly became clear that people in Black, Latino, and American Indian communities were significantly more likely to be hospitalized or die from the new disease than White, non-Hispanic Americans. While the work many scientists did to understand the virus and devise vaccines, diagnostic tests, and treatments made the news regularly, efforts to study and address racial disparities in COVID-19’s impacts were equally important.

When called to lead efforts to shrink those gaps, Gary H. Gibbons, M.D., and Eliseo J. Pérez-Stable, M.D., rose to the challenge. The two IRP investigators, who respectively lead the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), helped direct two federal programs dedicated to providing underserved communities with information about, and access to, COVID-19 testing, clinical trials, and vaccines. In recognition of their life-saving work, Drs. Gibbons and Pérez-Stable have been awarded the COVID-19 Response Medal, a special honor bestowed this year as part of the Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals. Also known as the “Sammies,” these annual awards recognize and celebrate exceptional work by government employees.

“Although it is structured as an individual award, in my view, the real credit goes to the folks on the ground who we worked with — those intrepid souls in community-based organizations who literally went door to door to talk to their neighbors, give them information, and encourage them to protect themselves,” says Dr. Gibbons.

Getting COVID-19 Tests to the Underserved

NIH’s RADx-UP initiative aimed to bring COVID-19 tests to communities around the US as quickly as possible and ensure that historically marginalized groups had access to testing.

Early in the pandemic, with research on COVID-19 vaccines and treatments already well underway, NIH received a special appropriation from Congress for the Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics (RADx) initiative, a $1.5 billion project created to develop and produce rapid COVID-19 tests. NIH directed a third of that funding to begin a parallel initiative called RADx-Underserved Populations, or RADx-UP for short.

The first phase of RADx-UP, which Dr. Pérez-Stable co-led with Richard Hodes, M.D., Director of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and Tara A. Schwetz, Ph.D., Associate Deputy Director of NIH, assigned $300 million to fund efforts to track the virus’ spread across the country and examine COVID-19 testing rates in different locations and among different groups of Americans. The initiative then used this data to develop strategies for partnering with established community organizations that would bring COVID-19 testing opportunities to underserved communities and help reduce testing disparities.

Unfortunately, testing was not the only public health measure lacking in underserved communities. After several COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out early this year, issues with access and trust quickly became a problem. The vaccines were difficult to get in rural regions and communities with fewer resources, and those in essential jobs — disproportionately individuals from minority groups — had difficulty getting time off to search for and attend vaccination appointments. At the same time, many people in communities that had grown to distrust the healthcare system due to a long history of medical neglect were electing not to get the shot.

“We always assumed that once we did the study and showed the benefit, of course everyone would take it,” Dr. Pérez-Stable says. “After all, this was the best vaccine we’ve developed in 50 years. But, of course, a lot of people didn’t rush to get it.”

To combat these trends, NIH rolled out the second phase of RADx-UP. The initiative continues to work with trusted community partners, including faith-based institutions, homeless shelters, and community clinics and centers, to educate people about the vaccines, identify and address barriers to access, and help people make and reach appointments where they can get the shot.

Working Toward Diversity in Clinical Trials

Certain groups, including Black Americans, have been historically underrepresented in clinical trials. CEAL aims to ensure this will not be the case for trials of COVID-19 vaccines and therapies.

Of course, before the COVID-19 vaccination campaign could begin, clinical trials were needed to show that the shots were safe and effective. As those studies began, NIH became concerned about ensuring diversity among clinical trial participants so that the resulting information could be applied to people of all backgrounds. To ensure diversity in clinical trials, Dr. Gibbons and Dr. Pérez-Stable were selected to lead a second program called the Community Engagement Alliance (CEAL) Against COVID-19 Disparities.

CEAL partners with researchers, vaccine manufacturers, and national and local organizations and leaders to ensure clinical trials for COVID-19 vaccines and therapies include Black, Latino, and American Indian participants, groups that are traditionally underrepresented in scientific studies. Dr. Gibbons and Dr. Pérez-Stable began by reaching out to NIH-funded investigators who had already built effective partnerships with the disadvantaged communities in their areas. This allowed NIH officials, scientists, and community leaders to come together quickly to create solutions tailored to specific populations.

“In the context of a rapidly moving pandemic, these partnerships wouldn’t happen if you helicoptered into those communities,” Dr. Gibbons says. “You really need to develop that trusting relationship with the team, based on the long-standing relationships that already exist.”

Dr. Gibbons and Dr. Pérez-Stable also met regularly with pharmaceutical companies developing the vaccines — Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and Novavax — to talk about ways to recruit diverse groups of participants. Thanks to the duo’s efforts, individuals from traditionally underrepresented groups made up a significant proportion of volunteers in all of the companies’ vaccine trials.

“It was really an all-hands-on-deck approach to get information out to the communities,” Dr. Pérez-Stable says. “Initially, we focused on recruiting people to the studies so that the research would reflect these communities. Then we had to offer information — and address misinformation — about the vaccine.”

More From the IRP

Blog

A Record-Breaking Sprint to Create a COVID-19 Vaccine

CEAL also worked with trusted messengers to develop and share information about vaccines and treatments as they became available. The Alliance’s decision to focus on local leaders and physicians, rather than stars like Oprah or star athletes, was key to its success.

“There’s research that says people really listen to local people they know,” says Dr. Pérez-Stable. “They trust their doctor. I remember a news report at the time about an African American physician in New Orleans who volunteered for a vaccine trial. It was just a two-minute story that showed her getting the shot, and it was just so much more powerful than anything a celebrity could do. People saw that and incorporated that kind of messaging into the campaign much more systematically.”

Challenging Misinformation and Disinformation

Despite the successes of CEAL and RADx-UP, convincing the many Americans who remain unvaccinated to get the shot remains a significant challenge.

Among communities of color, initiatives like CEAL and RADx-UP seem to be working. Dr. Gibbons points out that the gap in vaccine uptake between Black and White Americans has narrowed. Yet more than a year and a half into the pandemic, some segments of the U.S. population remain reluctant at best to get vaccinated, and there are still regions around the country with problematically low rates of vaccination.

“We’re still working on vaccine uptake, but I think we’ve made a lot of progress,” says Dr. Pérez-Stable. “Now the biggest challenge is with rural, White populations and minority populations who don’t want to participate in the studies or get the vaccines because they don’t trust the government. There’s actually misinformation being spread with malicious intent.”

While CEAL is continuing to partner with trusted leaders at the local level, Dr. Pérez-Stable believes the program will have to explore and implement additional strategies to reach vaccine holdouts. One step is to accelerate communication strategies to predict, identify, and disrupt the spread of misinformation and insert accurate information into discussions more quickly. Another potential approach is to use different appeals in vaccine-related messaging. For example, scare tactics like showing a 30-year-old man on a ventilator are controversial, but based on Dr. Pérez-Stable’s long experience with research on anti-tobacco campaigns, he believes they can be effective. It’s a frightening image, he says, but it also carries the message that your decisions can have a big influence on your risk for disease. Finally, structural changes, including mandating vaccines and implementing programs and policies to make it easier to get the vaccine, are likely needed. That’s an approach the Biden administration and increasing numbers of private companies have begun taking recently.

Photo courtesy of the office of US Representative Lauren Underwood

Dr. Gibbons (far-right) and Dr. Pérez-Stable (third from right) at a 2019 event focused on pregnancy-related complications in Black women. The duo’s prior work on health disparities for a variety of illnesses made them a natural fit for leading efforts to reduce similar gaps related to COVID-19.

“Mandating vaccines and imposing consequences for not taking them is hard, but it could be the one way to really push immunity up to 90 percent,” says Dr. Pérez-Stable. “We’ve been doing it for years with other vaccines in all 50 states. That’s been a real victory. If we could push the population of people resistant to getting vaccinated to less than 10 percent, I think we will be very close to getting control of this pandemic.”

Of course, even if COVID-19 were to miraculously disappear overnight, there would still be serious inequities in how certain diseases affects different groups of Americans, as well as how different populations interact with the healthcare system. Shrinking those gaps will require concentrated efforts that will last far beyond the current pandemic.

“Even after the pandemic is over, I think there are lessons to be learned about promoting inclusive participation in research and addressing misinformation and mistrust, as well as developing a strategy to engage partners in the communities to address social and structural issues that have been so vexing for decades,” Dr. Gibbons says. “It therefore speaks to the notion that this strategy is worth doubling down on for NIH over the long term to address a variety of health inequities that these communities face.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023