A Record-Breaking Sprint to Create a COVID-19 Vaccine

Kizzmekia Corbett and Barney Graham Recognized for Leading IRP Vaccine Research

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett (left) and Dr. Barney Graham (right) were named finalists for the 2021 Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals for leading NIH’s COVID-19 vaccine development effort.

At the end of 2019, most people were planning for a typical busy year in 2020. The world was looking forward to the Summer Olympics in Japan, the U.S. was deep into election campaigns, and IRP scientists at the NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) were designing vaccines for several coronaviruses in collaboration with a small biotech company called Moderna.

That all changed on a Saturday morning in early January. Chinese scientists had isolated a new coronavirus that was causing a serious epidemic in China’s Wuhan province and released its genetic sequence to the scientific community around the world. Barney Graham, M.D., Ph.D., director of the VRC’s Viral Pathogenesis Laboratory (VPL), and VRC research fellow Kizzmekia Corbett, Ph.D., dropped everything and immediately began working on a vaccine for the illness that would become known as COVID-19.

“Dr. Corbett was directing a team doing coronavirus work, and we had relationships with three or four really good academic collaborators and had been having monthly conference calls for years,” Dr. Graham says. “We also had our industry collaborators, and we had a strategy and all the technology, so we were ready to go.”

Dr. Graham’s lab is located in NIH’s Dale and Betty Bumpers Vaccine Research Center, also known as Building 40.

Dr. Graham and Dr. Corbett quickly mapped out a plan to begin experiments, assigned roles to team members, and went to work designing an antigen — in this case, a copy of the spike protein found on the surface of the COVID-19 virus, which it uses to infect cells. This antigen molecule, when provided via a vaccine, would trick the body into forming a defensive arsenal against future infection. After years of prior work to unlock the mysteries of coronaviruses and, with their partners at Moderna, perfect a method to coax the body to manufacture antigens via messenger RNA (mRNA), they were prepared. Less than 48 hours after the release of the novel coronavirus’ genome, the team had designed the protein that their candidate COVID-19 vaccine would use to teach the immune system to fend off the virus. Sixty-five days later, the VRC began clinical trials in collaboration with Moderna and clinical investigators from NIH’s Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Ultimately, the vaccine received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on December 18, 2020, just one week after a similar vaccine developed by Pfizer.

In recognition of this groundbreaking success in developing a life-saving COVID-19 vaccine in record time, Drs. Graham and Corbett were named finalists for the 2021 Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals, also known as the ‘Sammies.’ Often referred to as the ‘Oscars of government service,’ the Sammies honor exceptional work by government employees.

A Long Road and a Fast Finish

While creation of the specific vaccine for COVID-19 was surprisingly rapid, Drs. Graham and Corbett, along with fellow researchers in their field, had been laying the groundwork for decades. As a young chief resident in Tennessee, Dr. Graham began studying respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), an infectious disease that can be fatal in children. A vaccine made with the inactivated virus had been tested in the 1960s with tragic results — not only did it not work, but the disease worsened in children who received the vaccine.

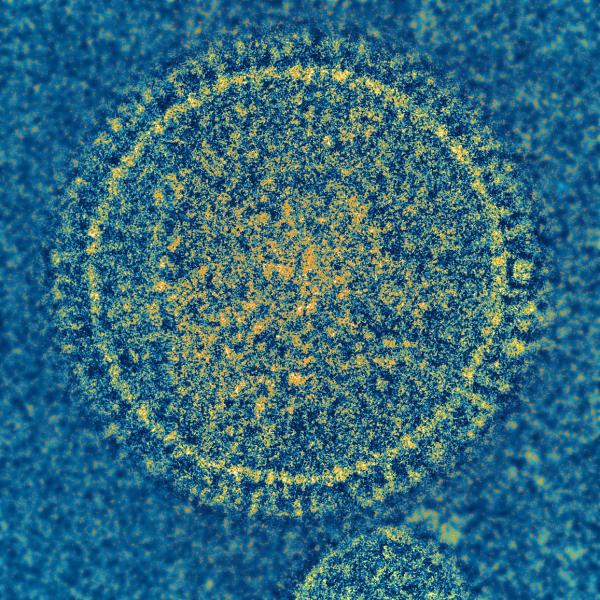

Dr. Graham’s research on the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), pictured here, left him well-situated to transition to studying coronaviruses like the one that causes COVID-19.

Eventually, Dr. Graham discovered that the original vaccine failed for two major reasons. First, the vaccine induced a response from immune cells called T cells that was more like an allergic response, making a lot of mucus and not effectively clearing the virus from the body. Second, inactivating the virus caused it to change shape to the form it takes once it has already infected and fused with a cell. As a result, the vaccine caused the body to release antibodies that could bind to the virus but could not block infection, making it ineffective. These findings set Dr. Graham on a path to create vaccines that could emulate the pre-fusion form of the virus. He continued the RSV project in 2000 when he was recruited to NIH to help create the VRC. Eventually, he and Jason McLellan, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of IRP senior investigator Peter Kwong, Ph.D., isolated and created 3D models of the pre-fusion virus protein. The new vaccine that used this pre-fusion version of the virus caused the body to produce antibodies 16 times more potent than the post-fusion antibodies elicited by the old vaccine.

“I just wanted to know what the shape of the pre-fusion protein was — I wanted to know how it was folded and what it looked like,” Dr. Graham says. “The intent was just to understand it, but that led to a vaccine approach that looks like it's probably going to work.”

In fact, the discovery of the pre-fusion structure proved foundational to the work Dr. Graham’s lab subsequently began on coronaviruses like SARS and MERS, both of which had previously caused worrisome outbreaks around the world. Some of this work was done in continued collaboration with Dr. McLellan, who had subsequently joined the faculty at Dartmouth University and now runs a lab at the University of Texas at Austin.

“After we had the RSV breakthrough, Dr. McLellan and I decided that coronaviruses were similar enough to RSV and there was no structural information for them,” Dr. Graham says. “That was a good area to work in because it was a wide-open field and it needed to be done.”

More From the IRP

Podcast

Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett — The Novel Coronavirus Vaccine

At that point, in 2014, Dr. Corbett joined the VPL as a senior research fellow and plunged full speed into understanding how the antibodies that bind to different forms of coronavirus spike proteins block infection. She also started developing a way for her team to quickly and reliably develop antigen proteins that could be tweaked to match each virus, as well as a method to deliver the instructions for making these proteins to cells via mRNA. The VRC was already gearing up for clinical trials with Moderna to test an mRNA vaccine against Nipah virus, which the lab had developed in parallel with an mRNA vaccine against the coronavirus that caused the 2012 MERS outbreak. As a result, by the time COVID-19 emerged, the VPL was poised to switch gears to a vaccine for COVID-19 and hit the ground running.

Inspiring Communities

In addition to her work on the Moderna COVID vaccine, Dr. Corbett has worked tirelessly on educating the public about vaccination and addressing vaccine hesitancy, particularly in communities of color. For the past year, her spare time has been filled with everything from television appearances and interviews to personally reassuring individuals and answering their questions. She even accompanied a young man and his mother to get their shots after the man expressed concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine at an MSNBC town hall. At the same time, Dr. Corbett hopes her new-found celebrity might motivate young people — especially women and minorities — to pursue careers in science.

“I try to tell my story because it’s not just that I don't even look like a scientist, but my background would suggest I could not be a scientist, ever,” Dr. Corbett says, “so I hope that people start to see that there's talent in different places.”

Photo by Chia-Chi Charlie Chang

President Joe Biden visits Dr. Graham (foreground, left) and Dr. Corbett (far-right) at the VRC in February 2021.

“20 Years of Work for a Thousand People”

As the frenzied rush to develop a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine winds down, both Dr. Graham and Dr. Corbett are planning their futures. Dr. Graham hopes to retire at the end of the year and devote time to improving communication and education about science and technology here and around the world. In particular, he’d like to see the establishment of more research capacity in low- and middle-income countries and improved dissemination of information and technology.

“I’ve been stunned by the lack of information and understanding,” Dr. Graham says. “We need to improve community education.”

In June, Dr. Corbett left NIH to lead her own laboratory at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where she’ll continue to study coronaviruses and “do work on things that hopefully will surprise people,” she says.

She’ll have plenty of options. As Dr. Graham points out, there are 26 different families of viruses known to infect humans.

“You should pick something within those 26 families that you find really interesting,” Dr. Graham advised her. “It may end up being the cause of the next big pandemic, or it may not, but there’s at least 20 years of work for a thousand people.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024