Leading the Charge Against Infectious Disease

Government Awards Recognize H. Clifford Lane’s Four Decades of Research Achievements

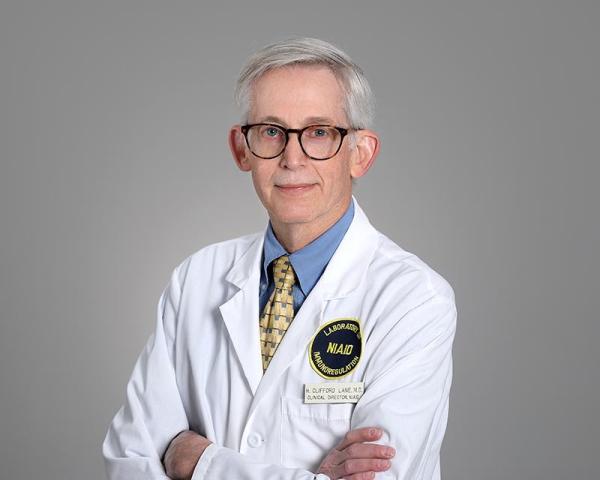

Four decades spent fighting a wide array of infectious diseases has earned Dr. H. Clifford Lane recognition as a finalist for the 2022 Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals.

The remarkable career of H. Clifford Lane, M.D., might have gone very differently if a NIH scientist hadn’t accidentally eavesdropped on Dr. Lane’s conversation with a colleague in 1979. After hearing Dr. Lane mention that he had missed the deadline to apply for a position at NIH, the NIH researcher made some calls and discovered a spot there had just opened up — one that was perfect for Dr. Lane, who would spend the ensuing decades conducting life-saving research to understand and combat some of the world’s most dangerous infectious diseases.

Now the Clinical Director at the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), Dr. Lane has been named a finalist for the 2022 Samuel J. Heyman Service to America Medals’ Career Achievement Award in recognition of his crucial contributions to the fight against HIV/AIDS, Ebola, COVID-19, and other illnesses. Also known as the “Sammies,” the awards recognize federal employees who are “breaking down barriers, overcoming huge challenges, and getting results.”

Dr. Lane began his NIH career in a nondescript manner, quietly studying how the immune systems of healthy individuals would respond to a molecule their bodies had never encountered before — in this case, a protein from a small sea creature that lives off the California coast. Soon enough, however, Dr. Lane was conscripted into a global public health crisis: the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

“That was obviously an extraordinary time because we were bringing in patients with this unknown, unnamed, horrible acquired immune deficiency and all the associated infections,” Dr. Lane recalls. “We began applying some of the same techniques we had been using to study healthy human immune responses to our patients with HIV/AIDS.”

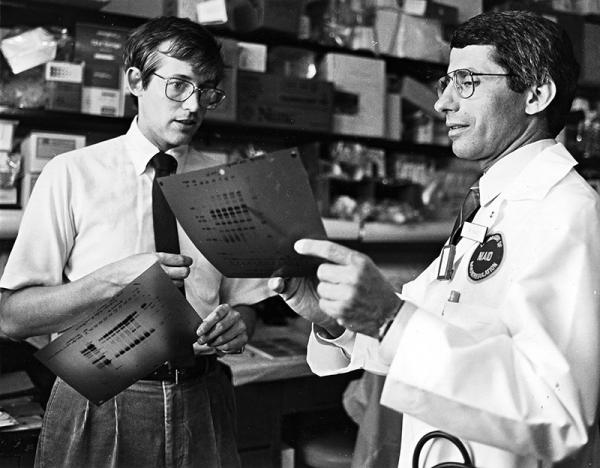

Dr. Lane (left) worked with Dr. Anthony Fauci (right) to combat the 1980s AIDS epidemic.

In 1981, Dr. Lane and his mentor, current NIAID Director Anthony Fauci, M.D., established the NIH AIDS research program. At the time, scientists had no idea what was causing the disease, so trying to treat it was like stumbling around in the dark. Based solely on the fact that AIDS patients had severely weakened immune systems, Dr. Lane and his IRP colleagues tried to treat a patient by transplanting immune cells and bone marrow into him from his healthy, identical twin brother, which yielded disappointing results.

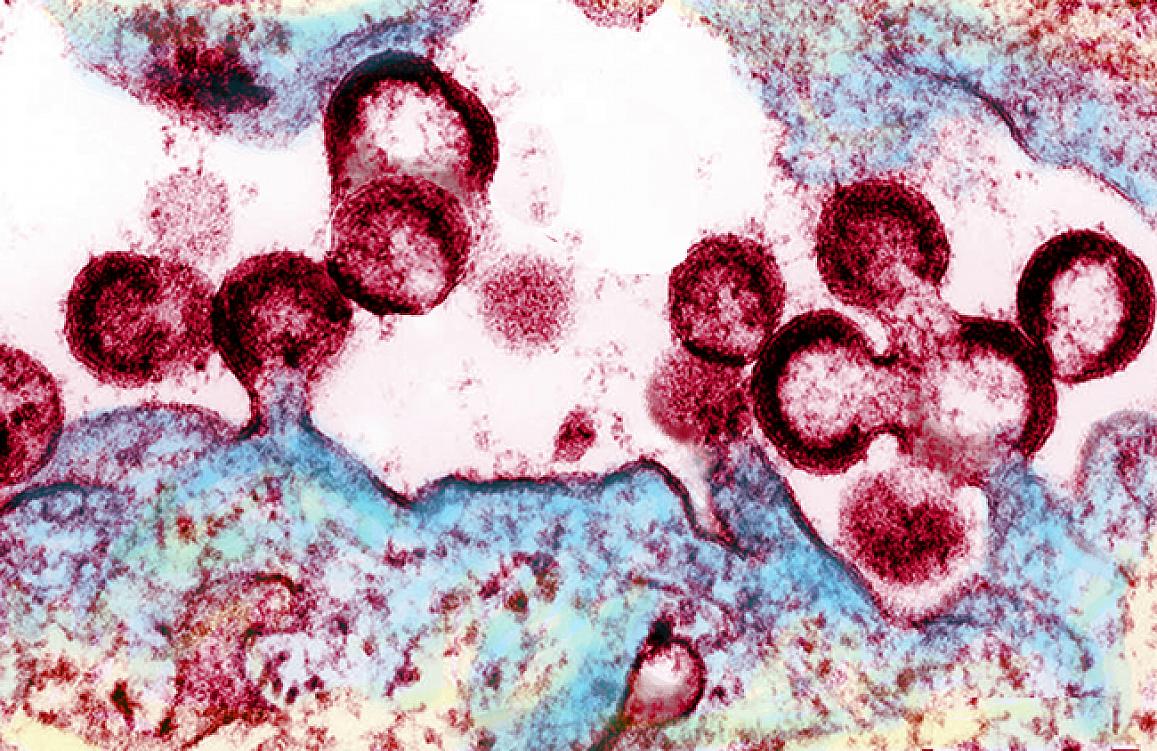

Fortunately, science was slowly turning the lights on in the dark room that was AIDS research in the early 80s. As other researchers began to pinpoint the virus that causes AIDS, Dr. Lane’s team built upon their findings. They learned, for example, that massive doses of interleukin-2, which at the time was being tested as a cancer treatment, could greatly boost levels of the specific immune cells that HIV destroys. Whether this could have any clinical benefit for patients, however, remained an open question.

To find the answer, Dr. Lane’s team needed to do a large, randomized control trial, something that required many more patients than the number being treated at the NIH Clinical Center. The group reached out across the world to form an international consortium to conduct the necessary large-scale studies. And while interleukin-2 didn’t ultimately pan out as a treatment for AIDS, Dr. Lane would subsequently spend his career promoting these sorts of trials in the field of infectious disease, an effort he says is one of his proudest achievements.

“The approach to clinical research has changed since I started,” he notes. “It evolved from doing small studies where we knew what treatment each patient was receiving to really doing robust, double-blind clinical trials, the way they had been done in heart disease and cancer.”

HIV viral particles (red) emerging from an infected cell.

Since organizing that large-scale AIDS trial, Dr. Lane has repeatedly helped bring sometimes disparate partners together to pursue many other rigorous studies of infectious disease around the world. In recent years, he has assisted governments and communities with developing evidence-based responses to major outbreaks from H1N1 flu in Mexico and H5N1 bird flu in Indonesia to Ebola in West and Central Africa. Most recently, he helped to establish NIH’s ACTIV initiative, a public-private partnership created to set research priorities and lead clinical trials for COVID-19. He also helped establish the NIH COVID-19 Teatment Guidelines, which provide constantly updated information about COVID-19 testing and therapeutic strategies. In addition to supporting strong science, he explains, these projects have required intensive political and social mobilization to ensure success, something he first encountered when working with AIDS activists in the 1980s who were advocating for access to unproven treatments.

“The concept of randomized, controlled trials was not something the activists warmly embraced at first,” Dr. Lane says. “However, once their thought leaders understood why we did research that way — that it is really the quickest way to get the most effective therapies to the largest number of people — they realized a poorly designed, underpowered trial wouldn’t move the field forward. The activist community had incredibly bright individuals and they became partners in the research.”

A study volunteer receives an inoculation at Redemption Hospital in Monrovia on the opening day in Liberia of PREVAC, a Phase 2 Ebola vaccine trial in West Africa.

Dr. Lane has learned that forming such partnerships with stakeholders both inside and outside the lab is key to successfully conducting studies on an international scale. That lesson particularly came in handy when organizing clinical trials in Liberia for an Ebola vaccine during the nation’s 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak. Dr. Lane and his colleagues met with community leaders, held town halls, put on skits — anything to convey the need to perform that research. Liberia already had quite a bit of social mobilization infrastructure in place for infection control and other aspects of public health, which Dr. Lane and his fellow Ebola researchers were able to tap.

“It’s amazing how the social buy-in is such a big part of science,” Dr. Lane says. “We saw it again with COVID, when we had to get everyone on the same page. It’s the tough part.”

While his career in infectious disease has expanded wildly in scope over the decades, Dr. Lane continues to lead groundbreaking work on HIV. In 2014, for example, Dr. Lane’s team discovered that broken bits of HIV genetic material floating around in the blood, which researchers had previously thought were harmless, might actually contribute to persistent stimulation of patients’ immune systems, even in those in which the intact virus was well-suppressed.

Moving forward, Dr. Lane hopes that the international work he and his IRP colleagues have been involved in can ultimately develop into a unified, global clinical research network that would mobilize to respond to emerging disease threats. For instance, building on the research capacity the group and its international partners helped build in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the country’s 2018-2020 Ebola outbreak, Dr. Lane and his colleagues had already begun planning for a clinical trial to test treatments for monkeypox prior to the current global outbreak of the disease, which the World Health Organization recently declared a “public health emergency of international concern.” That study is scheduled to begin in the next few weeks.

“What I like about infectious diseases,” Dr. Lane says, “is that even though patients can be quite ill, you can usually make a real, specific diagnosis, give them a real, specific treatment, and then watch them get better.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024