IRP’s Heinz Feldmann Elected to National Academy of Medicine

Vaccine Research Facilitated Rapid Response to Ebola Outbreak

Dr. Heinz Feldmann was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 2020 for his crucial contributions to the fight against Ebola.

IRP Senior Investigator Heinz Feldmann, M.D., was elected to the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) last year for leading the development of the technology that resulted in the first Ebola vaccine approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and used by the World Health Organization (WHO) to combat the deadly disease. Election to the NAM is considered one of the highest honors in the fields of health and medicine.

As chief of the Laboratory of Virology at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), Dr. Feldmann’s work focuses on viruses like Ebola that cause hemorrhagic fever, a condition marked by fever, weakness, muscle pain, and sometimes bleeding. These highly contagious viruses require specialized laboratories and strict safety procedures to study.

“It was a really nice surprise,” Dr. Feldmann says of his election. “I’m very happy about it because I still feel like a medical person even though I do mostly preclinical research. I hope to develop concepts and products that help people, so it’s a really special honor that peers recognize me in that field.”

Dr. Feldmann found his way into his current career after completing medical school and a doctorate in virology at the University of Marburg in Germany, where one of the viruses he studies, Marburg virus, was discovered. After completing his studies, his advisor encouraged him to apply for a National Research Council fellowship at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Although he intended to focus on the Marburg and Ebola viruses, soon after he arrived at the CDC in 1993, deadly cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, a rodent-spread infection, broke out in the Four Corners region of the southwestern US. The entire branch where he worked switched focus to that disease, which was killing young, healthy people just hours after they were brought to the hospital.

The experience of working with the CDC investigational team and visiting the clinical sites to combat the hantavirus outbreak was dramatic and intense, but it cemented his interest in public service. That set him on the path to eventually landing at the National Institutes of Health in 2008.

“I'm fascinated by public health and the community response to outbreaks,” says Dr. Feldmann.

Research on deadly, highly contagious diseases like Ebola requires strict safety practices and specialized laboratories that are only available at a few facilities worldwide, including a small number in the US.

His lab, which is located at the NIH’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana, focuses on learning more about a family of viruses called filoviruses and developing vaccines for them. Filoviruses are highly contagious and primarily zoonotic, meaning they live harmlessly in a ‘reservoir species’ — likely bats — but cause severe disease when they spread to humans or other susceptible mammals. The potentially fatal viruses cause a variety of dangerous symptoms from diarrhea and vomiting to fever and bleeding. Since there are no cures, treatment is usually supportive care to reduce symptoms while the body’s immune system fights off the infection.

Dr. Feldman began developing a vaccine for Ebola during a stint at the Public Health Agency of Canada — the “CDC North” as he calls it — and brought that work with him to the NIH. The vaccine his team developed uses a weakened version of a milder virus that affects certain livestock. His research group genetically altered that virus so that it produces the Ebola protein that provokes a protective immune response.

Unfortunately, vaccine development is driven by need, so until the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Western Africa, pharmaceutical companies were not particularly motivated to produce an Ebola vaccine. Infections like Ebola had historically occurred mostly in rural areas and could be successfully contained by isolating patients and tracking down their contacts, making vaccination campaigns less necessary than for other diseases.

“When I entered this field in the late 1980s, my mentors told me that with these viruses, we don’t need vaccines,” Dr. Feldmann explains. “There are not enough cases. Industry will not be interested in it because there is no market. And the people who would need the vaccine can never afford it, so demand rests with the governments.”

More From the IRP

Blog

An Ebola Therapy Two Decades in the Making

The terrorist attack that occurred in the US on September 11, 2001, and the bioterrorism threats that happened shortly afterwards were a turning point, Dr. Feldmann says. Suddenly, governments started to invest money in stockpiles of certain vaccines and treatments in the event of a natural disaster or bioterrorism threat. However, while this period saw increased funding for Ebola vaccine research, there was still little interest in manufacturing and testing Ebola vaccines specifically, as the virus was not seen as much of a threat.

After publishing its work on an Ebola vaccine in 2004, Dr. Feldmann’s team managed to find a small company to create a test batch, which sat on a shelf for about 10 years until the West Africa outbreak occurred. When it became apparent that the outbreak was much more widespread than previous events, governments and industry began seeking solutions. Luckily, Dr. Feldmann’s vaccine was available and ready for testing.

“I think this gave our vaccine a big advantage over some other approaches that were in pre-clinical trials,” he says.

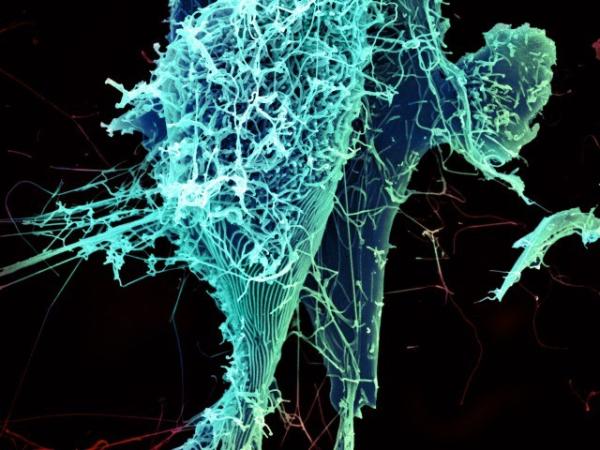

String-like Ebola virus particles shedding from an infected cell.

The vaccine developed by Dr. Feldmann’s team, now called Ervebo, became available for use toward the end of the 2014 West African outbreak. Since then, it has been used to halt every additional Ebola outbreak, such as recent ones in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Now a standard tool, Ervebo is administered through a process called ‘ring vaccination,’ in which, as soon as a case is identified and confirmed, a team traces that patient’s contacts and offers them the vaccine. This creates a protective ring of immunity around the first case to prevent further transmission to the wider community.

In addition to developing the vaccine, Dr. Feldmann’s laboratory has worked with clinicians in Africa to develop rapid, low-tech diagnostic tests that produce results in about two hours and can be used in local clinics and by mobile testing teams. Once a case is confirmed, epidemiology teams can immediately begin contact tracing. Previously, tests had to be sent to laboratories in the U.S. or Europe for analysis, and by the time the results came back, the patient had often already died and spread the disease to others.

Photo courtesy of PREVAIL.

A volunteer receives an injection as part of an Ebola vaccine clinical trial in Liberia.

“These are very remote areas in Africa and it’s not easy to do sophisticated high-tech diagnostics there,” Dr. Feldmann says. “There’s no power — you need to run equipment on car batteries or solar cells — so these tests are another big achievement for public health.”

Like the terrorism threats of the early 2000s, the outbreaks of Ebola, SARS, and MERS in recent years have led to much greater attention and funding for research aimed at combating infectious disease. That trend reached its zenith with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it clear that highly contagious viruses are not only becoming more common but can pose a monumental threat in our globalized world. Fortunately, the success of Dr. Feldmann’s Ebola vaccine shows that the scientific community is not powerless in the war against emerging infectious diseases.

“We’re always running behind nature, and I don’t think we’ll ever beat it,” Dr. Feldmann says, “but we’re closing the gap and that is exciting.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024