NIH’s Work With Native Communities Drives Diabetes Research

At the Confluence of Community and Clinic

CREDIT: NIDDK

Phoenix Indian Medical Center Campus: PECRB’s Clinical Research Center is located on the top floor of the Indian Hospital (large white building). The epidemiology groups operate out of the old Indian hospital shown in the foreground.

In Guadalupe, Arizona, a mix of Yaqui Indian and Hispanic families stepped off the sunbaked street and gathered in the annex building of a small NIH research clinic. It’s a space reserved for education where, for the past 10 years, clinical research participants have been collaborating with scientists. The families were eager to discuss the health issues that mattered most to them and wanted to know how biomedical research could be applied to help the community.

Today’s session, on how lifestyle and diet can help prevent childhood obesity and early-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D), was led by Madhumita Sinha, a physician with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases’ (NIDDK) Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch (PECRB), and her staff. The families are particularly vulnerable to developing these diseases and participate in research because they have a stake in ensuring a healthy future for themselves and their children. This community-based approach is just one of the multifaceted tools being used to stem the rising tide of obesity and T2D.

Other investigators at PECRB are zeroing in on biological elements. The Chronic Kidney Disease Section, headed by Robert Nelson, is identifying molecular mechanisms responsible for diabetic kidney disease and finding new ways to detect and prevent this complication. Its work resulted in a study published just this year (Diabetes 8:1603—1616, 2021; DOI:10.2337/dbi20-0043). An ongoing legacy of knowledge continues to be generated by PECRB and their research participants. “Since 1965, the branch has probably contributed more to the understanding of T2D than any other group in the world,” said Branch Chief Clifton Bogardus.

T2D now affects an estimated 6% of the global population and 13% of all U.S. adults—a prevalence nearly fourfold that of 40 years ago, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Previously known as adult-onset diabetes, T2D typically started in middle and late adulthood. But since the 1990s, the obesity epidemic has fueled a shift to younger ages worldwide, increasing the risk for complications such as heart disease and kidney failure within 15 years of diagnosis.

Yet, we already know of effective methods to mitigate this disease. Decades ago, research at PECRB in Phoenix, Arizona, as part of a multicenter clinical trial, demonstrated how weight loss and exercise can have a powerful effect on preventing or delaying T2D. A cure, however, has remained elusive. Researchers today are studying the genetic playbook of diabetes, which has revealed a complex interaction of biology and environment. And helping to unlock the mysteries of T2D for us all are minority groups that are disproportionately affected by the disease—including Hispanics, Alaska Natives, and American Indians, such as the Pimas.

A Changing Landscape

The Pimas call themselves Akimel O’odham, which means “River People.” Using irrigation farming techniques, their ancestors cultivated the arid Gila and Salt River valleys of Arizona’s south-central territory into a riparian green ribbon of agriculture. Adapted to an active, traditional lifestyle, the Pimas were both successful and generous. The Maricopa Tribe–driven from their homes in the 16th century by tribal conflict along the lower Colorado River–found refuge with the Pimas, where they continue to live today in the Gila River Indian Community (GRIC).

At the turn of the 20th century, nonnative farmers began settling the region. A series of upstream dams and irrigation projects diverted the waters of the Gila River, depriving the GRIC desert farmers of an agrarian way of life that had defined them for generations. Famine was followed by federal aid in the form of food such as canned goods, flour, and lard. The abrupt change in diet and forced change to a sedentary lifestyle led to a surge of obesity and diabetes. While the Arizona Water Settlements Act of 2004 would later restore water rights to the GRIC, disruptions to traditional ways of life had lasting health consequences: Two-thirds of Pima adults over the age of 45 now suffer from T2D.

Modern-day Phoenix is a diverse patchwork of ethnicities, including individuals from several tribal nations, and many choose to be invaluable participants in clinical research at PECRB. Staff here both conduct research and provide care for people with diabetes at clinics on the Phoenix Indian Medical Center campus, downtown Phoenix, and Valleywise Health Medical Center. Clinical trials are also run out of five sites in Arizona and New Mexico.

PECRB has been leading the charge of universities and biomedical institutions working on a cure for T2D. The branch has produced over 1,000 papers and generated discoveries that have benefitted both tribal communities and the growing number of people living with the disease. Indeed, PECRB’s work with the Pimas led to a unified definition of diabetes based on a glucose tolerance test that was adopted in 1980 by the World Health Organization. Since then, PECRB’s criteria for modifying or treating factors that put people at high risk for T2D and its complications have become standard practices of care.

Setting the Standard

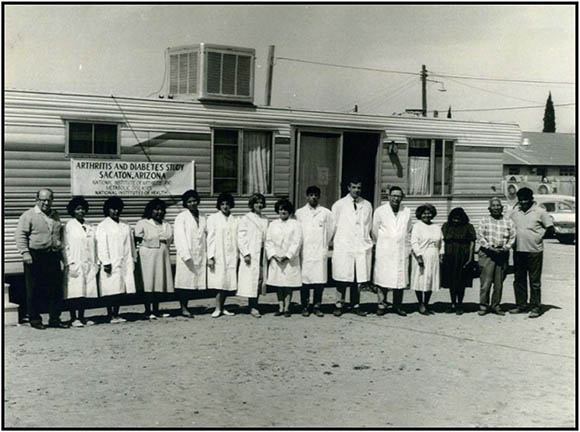

CREDIT: NIDDK

In the early 1960s, NIDDK, then known as the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, began research working out of facilities located in the Gila River Indian Community.

Peter Bennett, scientist emeritus and former Chief of PECRB, and subsequently William Knowler, until recently chief of the Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section, led a longitudinal population study that began in 1965 and would eventually span 43 years. This work, in collaboration with Bogardus, NIDDK Senior investigator Robert Hanson, and others, established obesity, insulin resistance, and inadequate insulin secretion as primary risk factors for developing T2D. Further investigation revealed evidence of heritability. T2D incident rates increased dramatically in individuals whose parents developed the disease before age 45. An even higher risk was associated with full Pima Indian heritage, yet another genetic indicator. But the strongest determinant they found was in children born to mothers who had diabetes during pregnancy—they were nearly certain to develop T2D by age 30.

Knowler’s work laid the foundation for the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). This landmark study, started in 1996, set an international standard for diabetes care and prevention in high-risk individuals. A lifestyle-change group reduced their risk of developing T2D by 58% when provided with intensive training on modest weight loss, eating less fat and fewer calories, and exercising at least 150 minutes per week. A second group reduced their risk by 31% with metformin, a drug that lowers blood glucose levels and improves how the body handles insulin. These participants took 850 milligrams twice a day and were provided standard advice about diet and physical activity. About half of the DPP’s nearly 4,000 participants were from minority groups—such as African American, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian American, Hispanic, or Pacific Islander—and most of these original participants continue to be followed today in the DPP Outcomes Study.

Traditional Lifestyle May Offer Protection

The notion that environment can exacerbate—or protect against—susceptibility to disease is well exemplified by the Pima Indians in Sonora, Mexico. Genetically similar to their Arizona counterparts, this geographically isolated group has largely maintained a traditional subsistence lifestyle. Living around the village of Maycoba in Mexico’s rugged Sierra Madre Mountains, the Mexican Pimas are primarily farmers and ranchers who maintain high levels of physical activity while providing for their families. They grow much of their own food consisting of beans, potatoes, and whole grains—a high-fiber, low-fat diet that contrasts sharply with their American relatives. NIH-funded studies here found drastically lower rates of T2D and obesity compared with the GRIC, offering further evidence of the protective role that a traditional lifestyle imparts (Curr Obes Rep 4:92–98, 2015; DOI:10.1007/s13679-014-0132-9).

Genetic Connections and Targeted Treatments

However, some forms of T2D have a strong genetic component. “If we can understand genetically which different pathways are being affected, we can find drugs that are better suited for an individual’s diabetes,” said Leslie Baier, chief of PECRB’s Diabetes Molecular Genetics Section, who has uncovered several genetic variants related to diabetes. In 2013, her group in collaboration with Hanson identified a common variant in the gene KCNQ1 that increases risk for T2D in the Pima population by impairing insulin secretion from pancreatic beta-cells. Because the GRIC studies can draw from generations of family data, the variant was traced to inheritance from the mother (Diabetes 8:2984—2991, 2013; DOI:10.2337/db12-1767).

Rare monogenic causes of T2D are being discovered, too. Established tribal research partnerships led to the creation of a genetic data array that uncovered a risk factor affecting some parents and their newborn children (Diabetes 64:4322–4332, 2015; DOI:10.2337/db15-0459). As a result, the research team reached out to educate community physicians on providing valuable interventions and care to these individuals in the hospital after delivery. In a separate study, altered function of MC4R—a gene known as a genetic variant hotspot—was associated with an extremely high body-mass index early in life (Hum Genet 133:1431–1441, 2014; DOI:10.1007/s00439-014-1477-6).

Discovering diversity in genetic architecture can help communities direct prevention resources to those who need it most—and moves the science forward. Baier sees potential for work in the genomic arena to benefit all those affected by T2D. “Even though a genetic variant might be unique to a specific ethnic group, we’re understanding physiology that will translate to other populations,” she said.

PECRB’s molecular genetics lab is also delving further into disease-causing mechanisms using engineered beta-cell lines. This exciting new research may guide investigators closer to personalized drug targets for T2D. “We can take [a variant] and look at what genes and pathways are affected at each stage of development and where is the best stage to intervene,” said Baier.

Building Community

Between the urban bustle of Phoenix and Tempe lies Guadalupe, a one-square-mile town that is home to 5,000 Hispanics and Yaqui Indians. The tight-knit community maintains many of its cultural traditions that blend Catholic rites with centuries-old Yaqui rituals, such as the festival of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Ten years ago, NIDDK set up a research clinic here, which has become a model for community-based participatory research.

CREDIT: MADHUMITA SINHA, NIDDK

Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section research staff at the Guadalupe clinic

“We are reaching out to the community as equal partners,” said Sinha, who is an associate research physician at PECRB’s Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section. “If obesity is a problem, you’re trying to engage the community and translate your research findings to a practical environment so it can frame health-policy decisions that are more acceptable to the people.” Her team has presented its research at town council meetings, the local elementary school, and even the fire station.

Since 2019, the Tribal Turning Point Study has been recruiting American Indian children, between 7 and 10 years old, who have obesity but not diabetes. Sinha is the principal investigator at Guadalupe, while two other sites in the Navajo Nation (a 17.5-million-acre territory that spans portions of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico) at Chinle, Arizona, and Shiprock, New Mexico, are overseen by the University of Colorado (Denver, Colorado). The intervention group participates in a structured lifestyle behavior program—tailored to the population by native leaders—while the control group receives educational information on general diets and activities. Researchers then study how these interventions affect a variety of biomarkers such as adiposity, lipids, glucose, and indicators of liver disease. The clinic at Guadalupe also happens to be part of the town’s church campus. “The people saw that we were working with children in their backyard, doing physical activity,” said Sinha. “I think that creates community awareness.”

This year, NIDDK will open a new research clinic in the Valleywise Health Medical Center (Phoenix, Arizona). Here, Sinha will oversee the Early Tracking of Childhood Health Determinants Study, an ambitious 23-year longitudinal and observational study backed by NIH’s Intramural Research Program. The study will follow 750 American Indian and Hispanic mothers and their children through 18 years of age to identify the intrauterine and early-life risk factors that contribute to obesity and metabolic risk in children. Sinha’s team plans to collect comprehensive medical data in addition to examining other socioeconomic and demographic influences during pregnancy. Diet, stressful experiences, sleep, and physical activity are among the many factors being tracked. The study aims to link these prenatal risk factors to a spectrum of health markers in the children such as adiposity, gut microbiome, and even cognitive development. “Obesity is not just biological, it’s shared environment, too,” said Sinha. “And the environment may be adverse.”

There are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States. Each is a sovereign nation with an independent government and culture and the potential to contribute to scientific discovery in an authentic way. NIH’s Tribal Health Research Office (THRO) is the central hub for coordinating tribal health research throughout NIH and serves as the single point of contact for both researchers and tribes.

“We can help create strategies and identify areas where tribes have unique differences,” said THRO Director David Wilson in a recent videocast on the ethical conduct of research with American Indians. That way researchers “have a better understanding of the community they are going into, and [these strategies] help get them off on the right foot.” He pointed to tribal institutional review boards and formal consultations between tribal leadership and NIH as ways to align expectations and ensure that research is meaningful to each community. “Tribes are very interested and willing to participate in biomedical research,” said Wilson. “But we have to offer them opportunities to be involved as true partners in the process.”

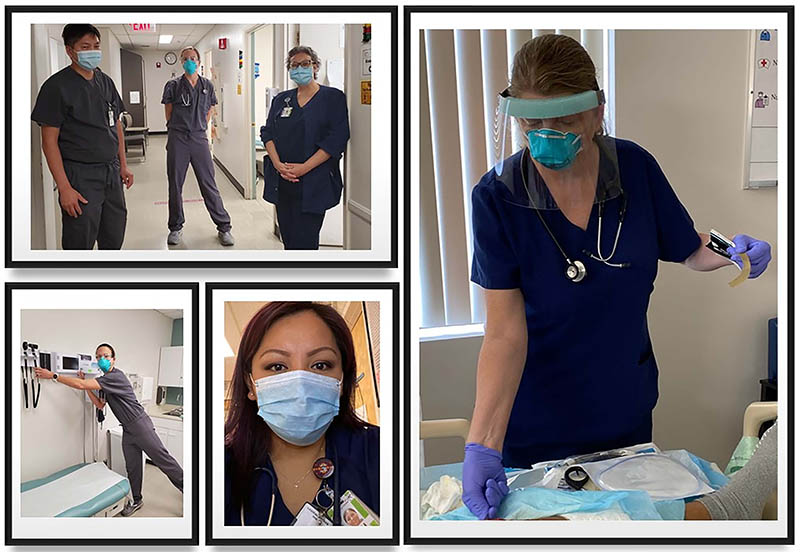

CREDIT: NIDDK

Shortly after the pandemic began, the PIMC sent out a call for volunteer health care workers to provide extra clinical care as the hospital prepared for the COVID-19 patient surge. Several PECRB staff members, including the branch’s clinical research nursing staff, medical director, and supervisory nurse practitioner, rose to the challenge. They’ve been continuously volunteering since the early stages of the pandemic to provide patient care, including for those with COVID-19.

Recent videocasts:

Clinical Center Grand Rounds: Physiologic and Genetic Studies of Diabetes in the Akimel O’odham (Pima Indians): https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=41794 (April 28, 2021)

Office of Human Subjects Research Protections Education Series: Ethical Conduct of Research with American Indian and Alaska Native Participants: Extending Protections through Respect for Tribal Sovereignty (NIH only): https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=42651 (September 2, 2021)

Michael Tabasko is a science writer-editor for The NIH Catalyst.

This page was last updated on Monday, January 31, 2022