A Conversation with NIH Director Francis Collins

Reflecting on Accomplishments, Advice, Music, and More

Francis S. Collins, who is stepping down from his post as NIH director by the end of the year, spoke recently with staff from The NIH Catalyst, the NIH Record, and the “I am Intramural” Blog. Following is an edited version of his comments.

CREDIT: NIH

Francis Collins.

Q. When you took this job in 2009, you penned an article in Science magazine (Science 327:36-37, 2010) in which you identified five areas you wanted to focus on as NIH director: 1) high-throughput technologies; 2) translational medicine; 3) benefitting health care reform; 4) a greater focus on global health; and 5) the reinvigoration and empowerment of the biomedical research community. What do you think you tackled successfully? And in hindsight, is there anything that you might have done a little differently?

COLLINS: I thought pretty hard about those themes. I consulted with [former NIH Directors] Harold Varmus and Elias Zerhouni about it. In each of those areas, we’ve made some real progress. Much of this has been assisted since 2015 by Congress supporting our need for sustainable and predictable increases in budgets. This has made it possible to start new projects that otherwise would have been hard to do.

High-throughput technologies: I’m pretty excited about the way in which technology has evolved to enable things such as the Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative. Additionally, some breathtaking advances have been happening with stem cells and single-cell biology.

Translational medicine: A big push for me in the first couple of years as NIH director was to create a specific entity at NIH that was focused on translational science. So we created the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, which has been remarkably successful in providing capabilities for NIH-funded researchers to take basic science discoveries into clinical applications. I am now hoping that President Biden’s proposed Advanced Research Projects for Health (ARPA-H) will be established at NIH in the next few months. ARPA-H could speed up the process of funding use-driven projects that could translate biomedical research into outcomes that would improve the health of all Americans.

Benefitting health care reform: I wrote in the Science article that reinventing health care is an urgent national priority and that NIH could make substantial contributions in such areas as comparative-effectiveness research, prevention and personalized medicine, and health-disparities research. That’s been happening in a big way.

Global health research: NIH is the largest public supporter of global health research in the world, more than any other agency. I wanted to be sure we were doing whatever we could to optimize it. We are co-leaders of a project called Human Heredity and Health in Africa that has supported more than 30 different African institutions working together in a network that has made it possible for a lot of cutting-edge science to emerge. Previously, there wasn’t a lot of research opportunity in those places and there was a real risk of losing a lot of the African talent. Although we’ve made progress, there are still challenges. We wish we’d been able to encourage more research capacity in low- and middle-income countries, as we’re facing a COVID crisis and would have benefited from better molecular surveillance, clinical-trial opportunities, and expanded vaccine manufacturing.

Reinvigorating and empowering the biomedical research community: We are investing in training and diversity. We are also trying to be sure that the necessary resources are there for people who are trying to do great science but were struggling a few years ago because the percent success rates for grant applicants was in the teens. It is better now at about 21 percent, but to fund all of the most meritorious research it should be even higher. Furthermore, diversity is a hugely important issue for our workforce, our grantee community, and our clinical-trials participation. Several years ago I put together a diversity working group of my advisory committee, and out of that came the creation of a new position, the Chief Officer for Scientific Workforce Diversity. The initial holder of that post was Dr. Hannah Valantine, and now Dr. Marie Bernard leads the office. In addition, we have made real strides in increasing diversity in our intramural program through the Distinguished Scholars Program.

In the extramural arena, we are starting the FIRST [Faculty Institutional Recruitment for Sustainable Transformation] program, which aims to inspire institutions to recruit cohorts of tenure-track faculty with specific interests in diversity. Here at NIH, we founded the UNITE program, which seeks to address structural racism within the NIH-supported scientific community. We are also revamping our health-disparities research effort to be more intentional and more focused on interventions.

Q. What were some of the top accomplishments for intramural and extramural research during your time as NIH Director?

COLLINS: There are many examples of intramural achievements I could point to. I could start with the remarkable work being done by John Tisdale’s team on using gene therapy to cure sickle-cell disease and by Steve Rosenberg’s team on cancer immunotherapy efforts that have shown how activating the immune system can provide dramatic responses to cancer, even for people with stage four disease. A bricks-and-mortar achievement was getting the funding for the new Surgery, Radiology, and Laboratory Medicine wing of the Clinical Center. Finally, the Vaccine Research Center’s development of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will be seen historically as one of the most significant scientific advances of this decade.

CREDIT: CHIA CHI “CHARLIE” CHANG

“The Vaccine Research Center’s development of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will be seen historically as one of the most significant scientific advances of this decade,” said Collins. At the HHS/NIH COVID-19 Vaccine Kickoff event, held at NIH on December 22, 2020, he received the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine.

Extramural achievements include boosting the success rate for early-stage investigators (ESIs) to receive RO1 grants; we funded more than 1,300 first-time ESI applicants last year compared with 600 in 2015. Now the top 25% of ESI applicants receive grants (before it was only the top 15%). I’m proud of that.

Successful new programs include the BRAIN Initiative, which as I mentioned earlier, is a remarkable interdisciplinary effort to try to figure out how the cells and circuits in the human brain do what they do. There’s been an outpouring of papers in Nature describing for the first time the cell census of the motor cortex in mouse and human at a level of detail unimaginable a few years ago.

I’d also like to point to the “All of Us” program, the effort to recruit a million Americans (we have about 430,000 so far) to serve as partners in a detailed study of all the factors that play out in health or illness. They are making their electronic health records accessible to researchers, getting their genomes sequenced, answering questionnaires about their health behaviors, wearing ambulatory sensors, and doing a lot of laboratory measurements. This is going to be a foundation for discoveries for decades to come.

Q. What advice do you have for explaining science in ways that anyone can understand? Can you tell us a bit about why an approachable communication style has been such an important component of your leadership?

NIH Director’s Blog.

COLLINS: Communicating our research is an important part of what all scientists are called upon to do. To be successful, a scientist needs to be aware of whether the information is actually getting across. One of the things that helped me was growing up in the theater. My father was a director and producer, my mother was a playwright, and I ended up on the stage at an early age. It was a small theater where you could see your audience and you knew if you were connecting.

Before coming to NIH, I taught medical students at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, Michigan). If you want to be humbled by your own communication deficiencies, this is a great way to discover them [laughs] because med students will turn you off really quickly if you’re not making sense on their level. I always try to imagine the typical background of the person in the group to whom I’m speaking, and how I could put forward a complicated scientific concept in a way that would resonate. I use analogies a lot, because they often help people anchor a scientific finding within a more familiar, everyday experience. I try as best I can to avoid using the jargon terms that science is famous for. Most importantly, I check out the body language of the person or group I’m speaking with to see whether I’m coming across, or whether I need to modify the approach. This is harder to do in the era of everything being virtual.

Q. You are our rock star. You started the Sound Health Initiative. And for these last 12-plus years, you’ve been entertaining us with solo performances and with your band. Could you tell us about your passion for music and music as a potential therapy for healing?

COLLINS: We live pretty intense, stressful lives, especially under COVID. We all need opportunities to get away from that intensity sometimes and experience something that’s uplifting and re-energizing. For me, music lifts my spirits and is just good therapy. It’s also an enjoyable way to share an experience with others. When the band is really in the groove, and we’re playing a song that’s rocking the house, you can’t help but feel good. Of course, under COVID, the band has not had any gigs because it has not been safe. I’ve really missed that. Right now, my musical experiences have been more of the solo variety, sitting down at the piano or playing my guitar just to change the dynamic after a very intense and busy day. That’s helped me a lot.

CREDIT: CHIA-CHI “CHARLIE” CHANG

Francis Collins enjoys playing with his band and performing solo for NIH audiences.

I do think there’s a lot we can learn about how music touches us in ways that can be uplifting and healing. And that’s what the Sound Health Initiative (an NIH–Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts–National Endowment for the Arts partnership) is all about. I started this with Renee Fleming, the best-known operatic soprano of our era. She’s become extremely knowledgeable and highly effective in this area of connecting science and music. And now NIH, through the Sound Health Initiative, is funding $20 million worth of research that brings music therapists together with neuroscientists to try to understand each other’s approach to how music can be effective in healing. I love the idea of bridging what is often seen as a gap between the humanities and the sciences.

Q. What advice did previous directors give you? And what insights about the job might you share with the next director?

COLLINS: I mentioned earlier the five themes that I put forward in 2009 when I became NIH director. A couple of long talks with Harold Varmus helped those ideas to come into focus. I also had a long conversation with Elias Zerhouni when I was nominated by President Obama. The thing that sticks with me most was [Zerhouni] saying, ”You have one critical priority that you must never let slip down the list: that is supporting the next generation of scientific talent.” This was in 2009 when funding was pretty tight. Elias was deeply worried that we were in such a discouraging place for young investigators that we were going to lose a whole generation of that group, never to return. I heard that message loud and clear and a lot of what I did in the course of these 12 years was to try to address it. I mentioned earlier that one response to this situation is to prioritize applications from early-stage investigators. That has more than doubled the number of such investigators who join our community of grantees each year.

Elias and I also talked about whether we were doing enough to build on the scientific capabilities that occur in the private sector. Elias had some familiarity with that and went on to be a major player in the private sector at Sanofi. That conversation inspired me to think a bit more about what could be done to accelerate progress in our complicated research ecosystem. As a result of that thinking and by getting to know some of the senior scientists in pharmaceutical and biotech companies, the Accelerating Medicines Partnership (AMP) emerged. It brought together the remarkable talent in both the public and private sectors to figure out ways to work together to identify biological markers of disease and the development of treatments that target those pathways. AMP initially focused on Alzheimer disease, diabetes, and rheumatoid arthritis and lupus. Later projects have added on Parkinson disease and schizophrenia. Even more recently, AMP has launched another project on gene therapy for rare diseases. AMP is a really powerful collaborative effort that didn’t exist before. As co-chair of the AMP Executive Committee with Mikael Dolsten of Pfizer, I am proud to see what has been accomplished. The level of trust that was developed between the public and private sectors through AMP turned out to be critical for the ability to establish rapid and effective collaborations on COVID-19, particularly the Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines public-private partnership.

If I was trying to advise the next NIH director, I would emphasize the importance of focusing on relationships with members of Congress. If you want NIH to flourish, you need Congress’ support and trust. You want Congress to have confidence in the NIH director, to know that straight answers will be provided when asked for. I’ve probably had close to 1,000 one-on-one visits with members of Congress in the past 12 years. And those usually go really well. Although members of Congress may seem to disagree about everything right now, they all see the value of medical research. Provided with a bit of information about NIH, they see what a remarkably important contribution we make to finding answers to all those conditions that they’re worried about on behalf of themselves, their families, and their constituents.

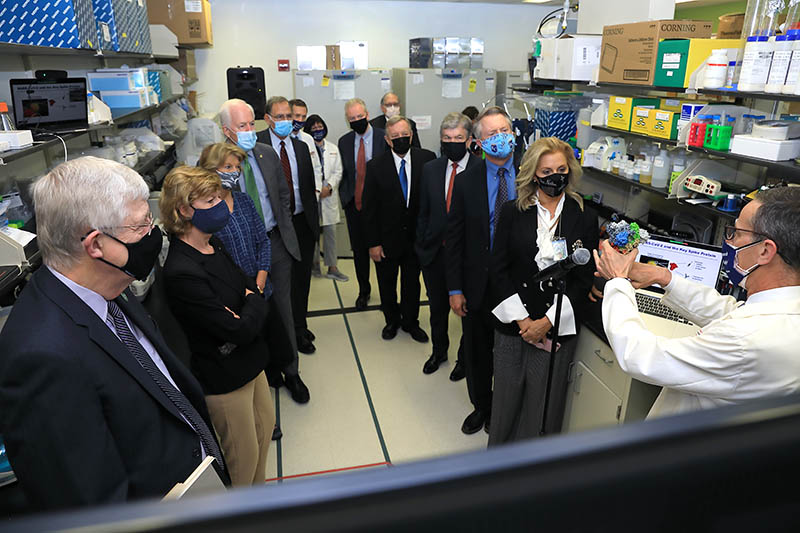

CREDIT: CHIA-CHI “CHARLIE” CHANG

As NIH Director, Francis Collins worked hard to build relationships with members of Congress, meeting with them one-on-one and inviting them to the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, to learn about NIH research. On May 17, 2021, a bipartisan contingent of United States senators and staff members visited NIH for science briefings, a lab tour, and biotech demonstrations. Shown: Vaccine Research Center Director John Mascola (right) describing vaccine research; Collins is on the far left.

Those personal relationships are crucial. The fact that we have seen our budget increase in the last six years has a lot to do with a few bipartisan heroes in the Congress. We’ve done everything we can to help them get to know us. They accept our invitations to come to NIH to visit us, they see what’s going on in research labs, they meet with patients in the Clinical Center, and they develop a real personal knowledge of what medical science is all about right now. So I’d say to the next NIH director: Never turn down an invitation to meet with a member of Congress, even if you’re really busy. That’s your top priority.

Q. What research areas do you see as being particularly important over the next, say, decade, and what do you think NIH’s role will be in those areas?

COLLINS: Well, it’s always hard to see much beyond a year or two because so many things happen that we didn’t expect. I never imagined that CRISPR gene editing would emerge so dramatically during my time as director and make a wide variety of scientific advances possible, from basic science to clinical applications. Certainly, there will be other advances nobody can predict.

CREDIT: ERNESTO DEL AGUILA III, NHGRI

CRISPR-Cas9 is a customizable tool that lets scientists cut and insert small pieces of DNA at precise areas along a DNA strand.

There are areas that I know will be full of potential that we’ll want to invest in: One example is neuroscience, in which new technologies will open up new insights to normal function and to the basis of brain disorders. Another area of rapid progress is likely to be artificial intelligence and machine learning.

I hope we’ll also make major progress in dealing with the opioid crisis and the need to find better answers for chronic pain. At NIH, the Helping to End Addiction Long-term Initiative aims to speed scientific solutions to stem the national opioid public-health crisis. This is urgent: We lost 90,000 people to opioid overdoses in the past 12 months.

In the area of immunology, mRNA vaccines have provided safe and effective vaccines for COVID-19 in a breathtaking 11 months. But mRNA vaccines might also advance the effort to prevent HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis–and might also lead to major progress in vaccines for cancer in the next few years.

Single-cell biology has transformed our ability to understand how life works and how disease happens, and this technology is just going to get better and better. Combined with a range of -omics approaches, it is now possible to ask a single cell, “What are you doing there?” by assessing RNA expression, chromatin structure, and, increasingly, proteomics.

Therapeutically, I’m really excited about where we’re going with gene therapy. In the next few years many of those 7,000 genetic diseases for which the DNA misspelling is known might be amenable to a scalable approach using in vivo gene therapy.

These are just a few examples of areas to watch–but there are dozens of other areas of investigation that are showing great promise right now. This is just a fabulous time to be involved in biomedical research.

Q. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

COLLINS: I love the NIH. Being NIH director is probably the best job in biomedical research. Serving as director during the worst pandemic in more than a century and seeing how the scientific community rose to the challenge with rapid advances in vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics has just been breathtaking.

The decision to step down has not been an easy one. But 12 years is a long time to be in this position, longer than any previous presidentially appointed NIH director. I wrestled with the decision over several months. But ultimately a scientific organization like NIH needs new vision and new leadership from time to time. The NIH institutes and centers are in terrific shape–I am proud to have recruited most of their directors. And I am confident the president will find a terrific leader to serve as the next NIH director, and that person will bring a whole raft of new and exciting ideas. I’m not going far; I will be hanging out in my NHGRI research lab in Building 50, immersing myself in some really exciting research on diabetes and a rare genetic disease called progeria. I will be cheering for the amazing people and projects that make NIH the National Institutes of Hope.

For more information about Francis Collins’s accomplishments, go to https://irp.nih.gov/catalyst/v29i6/francis-collins-to-step-down-as-nih-director.

This page was last updated on Monday, January 31, 2022