Heavy Drinking Linked to Smell and Taste Alterations

IRP Research Utilizes National Study’s Data to Explore Under-Examined Phenomenon

Scientists have extensively studied how alcohol use affects our senses of vision and hearing, but perhaps surprisingly, not many studies have explored its effects on smell and taste. Recent IRP research revealed curious insights into that relatively neglected question.

From the spicy Bloody Mary and sweet piña colada to salty margaritas and bitter cheap beers, alcoholic drinks span the entire spectrum of tastes. It’s not a far leap, then, to think that the sense of taste can influence alcohol consumption habits, and vice-versa. A recent IRP study dove into this question, ultimately discovering a number of ways that smell and taste perception differ in people with high-risk drinking habits.1

It’s common to hear that alcohol is an acquired taste, and I still distinctly remember the reek of beer in my college’s dorms during the weekend. However, despite the strong sensations that are connected to alcohol, few studies have looked at the relationship between alcohol consumption and our senses of taste and smell — the latter of which significantly influences the former. For the new study’s senior author, IRP Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Paule Joseph, Ph.D., that’s a glaring hole that needs to be filled.

“When you look at the scientific literature, there’s quite a lot more on the visual and auditory systems in individuals with alcohol use disorder than smell and taste,” she says. “Odors may help us better understand alcohol dependence due to their significant role in shaping addictive behaviors — when you go to a bar, you can smell the alcohol, and that elicits certain reactions. Also, in someone who has been a heavy drinker for a long time, certain neurological systems are deteriorating, so it’s useful to know what happens when people expose their smell and taste systems to routine alcohol consumption.”

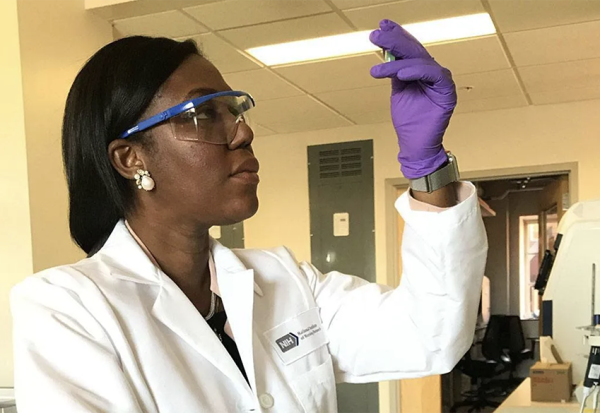

Dr. Paule Joseph, the new study’s senior author

To explore those kinds of questions, an IRP team led by Dr. Joseph and the study’s first author, Khushbu Agarwal, Ph.D., a former postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Joseph’s lab, turned to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The study, conducted annually by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since 1999 — and intermittently since the early 1960s — surveys a wide swath of Americans on numerous topics related to health and nutrition. Dr. Joseph and Dr. Agarwal were particularly interested in the NHANES data from 2013 and 2014, since 2011-2014 was the only period in its history when the study assessed participants’ senses of smell and taste.

“This was the only time that, for this area of research, we were able to have a nationally representative sample, so this dataset is very valuable,” Dr. Joseph explains. “Since 2014, the smell and taste survey has not been done again, and most datasets are very small.”

Prior research by Dr. Joseph’s team had discovered that heavy drinkers often experience odor hallucinations and find that smells they used to enjoy have become unpleasant, but the IRP team's new analysis of the NHANES data revealed that alcohol habits are associated with less dramatic shifts in smell and taste as well. For instance, compared to light drinkers and non-drinkers, heavy drinkers were less likely to correctly state that a bitter-tasting liquid was bitter. However, despite their deficiency in correctly categorizing a bitter taste, heavy drinkers did not differ from other participants in how intense they perceived the bitter liquid to be, and their perception of a salty one did not differ from that of the other two groups.

Dr. Joseph (right) conducts sensory testing similar to what was done in the NHANES survey from 2011 to 2014.

“A person might sense that something is very strong or faint without being able to identify what it is, and this is common in people with sensory deficits,” Dr. Joseph says. “They can detect a taste or smell but they cannot recognize or name it.”

Measuring the sense of smell revealed even more differences among people with different alcohol consumption habits. For one thing, heavy drinkers were worse at correctly identifying the smell of natural gas, a concerning finding given that gas leaks can pose a significant health threat. On the other hand, heavy drinkers were better at correctly identifying pleasant odors like the smell of strawberries.

“This suggests that alcohol use may heighten sensitivity to pleasant chemosensory stimuli while dulling awareness of potentially harmful odors, potentially reinforcing drinking behaviors,” Dr. Joseph says. “This imbalance could reflect changes in the brain’s reward system, which we already know exist, and now we can see it reflected on a non-invasive sensory test.”

Findings like these, Dr. Joseph believes, are a necessary starting point for beginning to address, and potentially reverse, the effects of heavy alcohol consumption on smell and taste. For instance, changes in those senses may lead to unhealthy eating habits and nutritional deficiencies, and interventions that retrain those senses may help people both eat better and reduce their alcohol consumption.

The foods commonly associated with alcohol consumption aren’t typically the healthiest, and alcohol-induced changes to smell and taste may increase the consumption of those kinds of foods in addition to stimulating greater alcohol use.

“Changes in the brain’s reward pathways could enhance cravings for highly processed and calorie-dense foods,” Dr. Joseph says. “Think about how bars often serve snacks like pretzels, chips, or fried foods — these high-salt, high-fat options can amplify the desire to keep drinking. There are several possible explanations, but a plausible one is that consuming these foods can intensify cravings for more rewarding substances like alcohol, creating a reinforcing loop of eating and drinking. I think that if we can target these sensory and neural changes, we could develop strategies that not only improve eating habits, but also help reduce alcohol consumption.”

Dr. Joseph is building on these initial results by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate how brain structure and activity differ in people with different alcohol consumption habits. In addition, she is teaming up with IRP investigator Veronica Alvarez, Ph.D., to explore alcohol’s effects on smell- and taste-related parts of the brain in animal models. Beyond her own research, Dr. Joseph hopes the recent study’s findings will help spur the inclusion of smell and taste evaluations in other scientists’ work and in the doctor’s office.

“There’s growing momentum towards universal smell and taste testing during routine medical visits, similar to what we do with vision and hearing screening, whether someone drinks alcohol or not,” Dr. Joseph says. “Establishing these sensory baselines is crucial for detecting early signs of health issues. Right now, we don’t assess these senses in a systematic way, and we don’t have clinical guidelines, which makes early detection and monitoring challenging. Even a simple smell test could provide valuable insights into overall health and well-being.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Agarwal K, Schaffe-Odeleye T, Marzouk M, Joseph PV. Reduced Bitter Taste and Enhanced Appetitive Odor Identification in Individuals at Risk for Alcohol Use Disorder: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2013-2014. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2024 Nov 26. doi: 10.15288/jsad.24-00104.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 21, 2025