Stress-Relieving Chemical Could Combat Alcohol Use Disorder

Targeting Brain’s Stress Circuitry Curbs Rats’ Alcohol Consumption

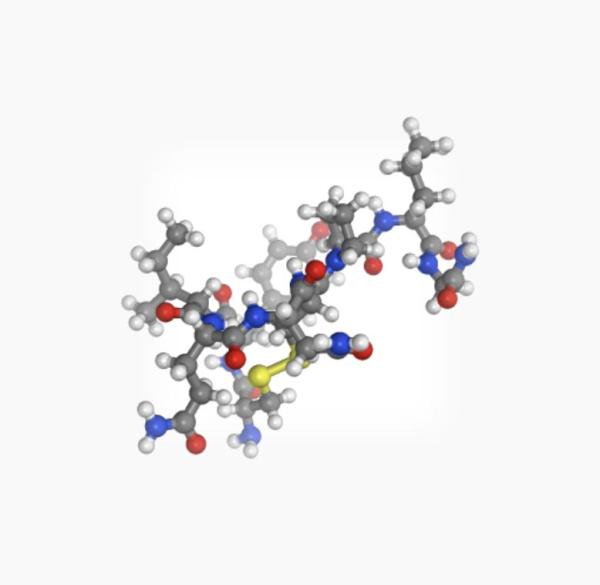

IRP researchers recently found evidence that the hormone oxytocin, pictured above, could be useful for curbing alcohol abuse.

For social drinkers, alcohol brings to mind barbecues and bar-hopping with friends, but for the roughly 16 million Americans with alcohol use disorder (AUD), drinking is a source of significant stress. Unfortunately, those negative emotions — particularly those experienced during withdrawal — drive people with AUD to drink even more. A recent IRP study points to a potential way to curb the desire to drink in people who abuse alcohol by altering the behavior of a brain structure that governs negative emotions.1

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a huge public health issue around the world, and though current treatments are certainly useful, they have limitations. The medication naltrexone, for example, can reduce drinking by stymying alcohol’s effects on the brain’s reward system, but many AUD patients simply stop taking it. Rather than attempting to make alcohol less pleasurable, researchers in the IRP’s Neurobiology of Addiction Section are pursuing a different strategy.

“We see alcohol use disorder primarily as a stress disorder,” says IRP staff scientist Leandro F. Vendruscolo, Pharm.D/Ph.D., one of the new paper’s senior authors. “The more that people drink, the more they become tolerant to alcohol’s rewarding properties. At the same time, stress systems in the brain start to become sensitized, so our approach is not to block the rewarding properties of alcohol but rather to normalize the hyperactive stress systems that we believe drive alcohol drinking in AUD.”

In an attempt to suppress the brain’s stress circuitry, the IRP team turned to a chemical called oxytocin that is produced by the human body and has been a mainstay of addiction research for years. However, while oxytocin has been shown to curb alcohol consumption in animals that are not physiologically dependent on alcohol — possibly by making alcohol less pleasurable — it has never been tested in alcohol-dependent animals, which can serve as a model of AUD.

The researchers found that alcohol-dependent rats that inhaled an oxytocin spray drank less alcohol, whereas the treatment did not reduce drinking in nondependent rats. What’s more, in a test of the animals’ motivation for alcohol that required them to work harder and harder for each successive drink, the oxytocin spray caused alcohol-dependent rats to more quickly give up on the task, but it did not have this effect in nondependent animals. It also had no effect on movement, motor coordination, or the desire to drink other types of pleasurable solutions like sweetened water.

“A person with AUD who is highly motivated to consume alcohol might do so even if there are consequences that should limit their consumption like legal repercussions, family issues, or missed time at work,” says IRP postdoctoral fellow Brendan Tunstall, Ph.D., the paper’s first author. “We wanted to measure not just how much the rats drink, but their effortful seeking of alcohol.”

Delivering oxytocin directly to the brain similarly reduced alcohol consumption in the dependent rats. Interestingly, a synthetic chemical that mimics oxytocin and cannot cross between the body and the brain through the blood-brain barrier also curbed alcohol consumption when it was injected into the brain but not when it was injected into the body. This finding provides strong evidence that oxytocin reduces alcohol-dependent rats’ drinking by acting directly on the brain rather than through some other system in the body.

To further support that conclusion, the IRP team’s collaborators at The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, examined neurons from a part of the brain called the central amygdala, which plays a key role in stress. Central amygdala neurons from alcohol-dependent rats responded very differently to both alcohol and oxytocin compared to neurons from their nondependent counterparts. This suggests that oxytocin reduces drinking by alleviating alcohol-induced changes to the stress circuitry in the central amygdala.

How exactly oxytocin and alcohol affect the central amygdala remains unclear, and the researchers must also see if they can repeat their results in female rats, since all the rats they have studied so far have been male. They also plan to test oxytocin-like molecules that could have longer-lasting effects and other properties that might make them a more effective treatment for people with AUD.

“The rat brain and the human brain are very similar in the functions and dysregulations that we believe drive the motivation for alcohol,” says Dr. Tunstall. “Of course, we have to try this in people and see how the clinical trials bear out, but we are always excited for anything that could increase the range of treatments available for AUD.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Oxytocin blocks enhanced motivation for alcohol in alcohol dependence and blocks alcohol effects on GABAergic transmission in the central amygdala. Tunstall BJ, Kirson D, Zallar LJ, McConnell SA, Vendruscolo JCM, Ho CP, Oleata CS, Khom S, Manning M, Lee MR, Leggio L, Koob GF, Roberto M, Vendruscolo LF. PLoS Biol. 2019 Apr 16;17(4):e2006421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006421.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024