Postbac Poster Day Presents a Buffet of Biology

Young Scientists Demonstrate Fruits of Their IRP Research

There’s nothing quite like visiting NIH’s Postbac Poster Day to boost your faith that the future of biomedical science is bright. On May 1 and 2, more than a thousand recent college graduates participating in NIH’s Postbac program showed their colleagues, friends, and family the fascinating projects they’re working on in IRP labs. From delving into the aging brain to making sense of the bacteria on our skin, these aspiring researchers demonstrated that they have the passion needed to unravel the most complex mysteries of human biology. Read on to learn about the scientific questions just a few of them have been doggedly investigating over the past year.

Monica Mesecar: Accelerating Our Understanding of Healthy Aging

Science has been a constant throughout Monica’s life. When some girls might have received dolls or clothes as gifts, her parents, including her scientist father, provided her with a microscope and kits for growing crystals and raising butterflies.

“My interest in science has been ever-present,” she recalls. “I was always a curious child, constantly asking ‘why?’ I am also very privileged in that my father is in science as well, and he shared his passion with me. I remember visiting his lab as a kid and being mesmerized.”

In high school, Monica’s broad scientific curiosity began to focus on psychology, leading her to study neuroscience at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. After graduating, she joined the lab of IRP senior investigator Mark Cookson, Ph.D., where she has been investigating how brain cells and their genes change as people age. While Dr. Cookson’s lab mainly focuses on neurodegenerative disorders that cause brain cells to die, Monica has instead been tasked with sorting through the various changes that happen in the brains of people who age without being diagnosed with a neurological condition.

“Many similar studies focus on pathological aging, rather than normal aging,” she says. “Researching what happens during typical aging will allow us to establish a baseline for comparison so we can better understand how these patterns may go awry in pathological cases.”

By taking advantage of a cutting-edge technique called single-nucleus RNA sequencing, Monica has identified processes that rev up or down in specific cell types as people age. For instance, she has found evidence that genes related to inflammation become more active over time in immune cells found in the brain called microglia. In addition, she has found that even in people with no evidence of brain disease, the activity of genes related to the risk of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease changed as her study participants aged.

“Given that some degree of change in the activity of genes related to disease risk may be normal throughout aging, this begs the question of what changes ‘push someone over’ into developing disease,” she says. “Having this baseline for comparison from individuals with no evidence of disease may help us answer this question.”

In addition to learning from the huge IRP community around her, Monica has benefited over the past year from being a participant in the Postbac Enrichment Program (PEP) run by NIH’s Office of Intramural Training and Education (OITE). Through the program, Monica attends seminars on leadership, professional development, and personal well-being along with others in the PEP program, which has helped her bond with the smaller group of fellow postbacs all going through the program with her. That’s not to say, however, that her connections with her IRP colleagues outside the PEP have not also been incredibly enriching for her.

“It’s been amazing to be so close to renowned researchers and absorb as much knowledge as I can,” she says. “The difference here is the frequency and abundance. At other places, you may get such opportunities once in a while, but here, there’s a pretty much constant influx.”

“I will also say that, as a postbac with a physical disability, I’ve found the NIH to be the most accommodating research environment that I’ve experienced thus far,” she adds. “That’s made me feel really comfortable here.”

Fun fact: During high school, Monica won second place in a local photography competition with what she describes as a “film noir-inspired project.” Her win, she recalls, was “really exciting because that was the first time I had been recognized for an achievement outside of academics.”

Andre Tulloch: Diving Into Racial Disparities in Pregnancy Outcomes

When you ask most NIH postbacs about their college major, you tend to hear a mix of biology, neuroscience, and psychology, maybe with some physics and chemistry thrown in. Andre brings a unique background to his IRP research, having majored in Social Justice at the University of Rochester in New York — with a minor in Biology, of course. He became interested in both topics while spending time with his grandmother in Jamaica during many summers and his entire fourth grade year, but the two subject domains also have personal meaning for him due to health struggles he has witnessed in his family.

“The flora, fauna, and technological differences of living in the countryside of Jamaica made me interested in biology and the way we depend on the land to survive,” he says. “I also have an interest in supporting healthy pregnancies, especially for Black women. This interest came from witnessing my mother’s lupus diagnosis and its effects on her pregnancy with my younger siblings.”

That specific interest in the health of Black women led Andre to join the lab of IRP senior investigator Stephen Gilman, Sc.D., where he has gotten the chance to “study the social and behavioral aspects of pregnancy, motivated by a broader interest in the health impacts of structural racism, particularly for birthing people,” he says.

Andre’s most recent research endeavor in Dr. Gilman’s lab examined how race relates to a marker of inflammation throughout the body known as C-reactive protein (CRP), which is linked to a higher chance of several medical conditions, including heart attacks. Andre found that Black pregnant women had higher concentrations of CRP during all three trimesters of pregnancy compared to women of other racial backgrounds, and they also gave birth to babies with lower weights, which can have long-term consequences for a child’s development. However, when Andre investigated the role of CRP in the relationship between race and birthweight, he saw it didn’t appear to be involved.

“My findings raise more questions about what other physiological processes might be causing race-based differences in inflammation and racial inequities in birthweight,” he explains. “Structural racism manifests in many ways to alter the way that Black birthing people experience pregnancy, which can lead to higher levels of stress during the process. I hope to explore other ways that this stress and discrimination can impact the physiology of pregnancy through other biomarkers. Ultimately, I hope to support a deeper understanding of what resources or aids can be provided during pregnancy to lessen the incidence of negative birth outcomes, especially for Black birthing people.”

As Andre has pursued research that he is strongly passionate about, he has also enjoyed getting to know his IRP colleagues, whom he describes as “a network of scholars doing some really cool work.” He has particularly enjoyed participating in the Postbac Enrichment Program, having built a strong community with the program’s other participants.

“We’ve become like a family, and I’ve been able to depend on them during my time at the NIH,” he says.

Fun fact: Andre collects vinyl records and currently owns more than 750 of them. His collection is “mostly a mix of old reggae and soca records with a good mix of newer R&B and neo-soul albums,” he says.

Gabriel Sanchez: Watching Water Changes in the Body

As a first-generation college student, Gabriel’s first chance to immerse himself in scientific research came when he enrolled at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia. He took great advantage of that chance, doing research on an array of topics from the synthesis of metal nanoparticles to how the brain helps us remember and navigate our surroundings. Probing the mysteries of the nervous system captured his curiosity the most, so he decided to major in neuroscience, a field that was new to him at the time.

When it came to choosing a lab to work in at NIH, though, Gabriel decided he wanted to venture out of his comfort zone once again. His thirst for novelty led him to the lab of IRP senior investigator Kong Chen, Ph.D., whose team studies how our metabolism — the process by which the body turns food into fuel — affects our health, and vice-versa.

“When I applied to NIH, I actually decided to go out of the field of neuroscience and explore metabolic research in hopes to just build new perspectives about science,” he says. “Now I get to work on projects that show how the nervous system and metabolism actually work in tandem.”

So far, Gabriel’s efforts have centered on examining how metabolism differs in different populations, including individuals of different ages and different racial or ethnic backgrounds. As part of that project, he is working on validating a way to measure the body’s water content using a technique called bioelectrical impedance spectroscopy, which sends a weak electrical current through the body to determine the amount of water inside and outside cells. This way of measuring the body’s water content is non-invasive and lower-cost than other approaches, but it’s unclear right now if it does the job as well as the ‘gold-standard’ ways of measuring water in the body. Since body water content is related to how well-hydrated and well-fed people are, finding an easy and cheap way to measure it could add more detail to the Chen lab’s studies of metabolism in different populations.

“The information gathered in this study can benefit science because we’ll have information about body composition and metabolism for people affected by various diseases, undergoing lifestyle changes like having a baby or changing weight, and having various backgrounds, ages, and sexes,” Gabriel explains.

“Scientists have typically used measures like height and weight to estimate how much a person uses food or calories as energy, and this is what we know as a 'metabolic rate,' but metabolism varies greatly between people based on those differences I previously mentioned,” Gabriel adds. “Because of that, scientists now believe that the older formulas that estimate metabolic rates might not work well for the general public, so we want to find more accurate ways to measure someone’s metabolism. This is important because it can help us assess risk factors for certain conditions like diabetes or obesity. A person with certain metabolic diseases could have a different metabolic rate, for example.”

For Gabriel, the thrill of venturing into an entirely new domain isn’t the only perk of doing research at NIH. He has also enjoyed building relationships with his mentors and colleagues, both in his own lab and all around the IRP.

“As a postbac, I have gotten the chance to learn from and work with some of the brightest minds on the planet,” he says, “and it makes me motivated and driven to continue learning so that I can hopefully leave my own mark in the world of science and medicine.”

Fun fact: Gabriel has both U.S. and Mexican citizenship and has gone to Mexico several times to teach science to middle school students.

Kiana Allen: Reining In Runaway Immune Cells

Kiana traces her initial interest in science and medicine back to her aunt, who served as a babysitter for Kiana and her cousins and lost both her legs to an undiagnosed case of lupus, an autoimmune disease.

“Growing up, I didn’t understand much about her condition, so my questions and curiosity about human biology began to pile up,” Kiana recalls.

That curiosity led her to follow a pre-med course curriculum and major in Biology at Alcorn State University in Lorman, Mississippi, a historically black college. And although she did not conduct any research at Alcorn State, Kiana was still able to hit the ground running as an NIH postbac with the help of the experience she gained spending the summer of 2021 in an IRP lab through NIH’s Summer Internship Program (SIP).

Her research during that summer focused on how genetics and biological sex affect health as people age, as well as how various interventions affect lifespan in mice, but when it came time to choose a lab to work in as a postbac, Kiana decided to try something entirely new. The COVID-19 pandemic had gotten her interested in how the immune system fights infectious disease, so she opted to worked with IRP staff clinician Jeffrey Strich, M.D., in the NIH Clinical Center’s Critical Care Medicine Department, where she has been contributing to research on the body’s response to several different diseases, including sepsis and the novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

“Dr. Strich’s team allows me to gain in-depth knowledge about the innate immune response in critically ill patients through basic and translational research,” Kiana says.

At Postbac Poster Day, Kiana presented her research on sepsis, a potentially lethal, out-of-control immune response to infection. One element of this runaway immune response is that cells called neutrophils release web-like meshes of DNA and antimicrobial proteins that capture and kill infectious invaders. These so-called ‘neutrophil extracellular traps,’ or NETs for short, are initially helpful but can cause problems when produced in excess. Kiana has found that a drug called fostamatinib, which inhibits an enzyme known as spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), reduces the amount of NETs that neutrophils produce when exposed to blood from sepsis patients.

“There is no FDA-approved drug to target this overactive immune response caused by sepsis,” Kiana explains, “While my work is in isolated cells, it provides insight that SYK inhibition can be a potential therapeutic for the dysregulated innate immune response in sepsis.”

As much as Kiana has enjoyed the day-to-day of conducting research in an IRP lab, her favorite moment as a postbac occurred outside the boundaries of NIH’s campus. In October 2023, she got the chance to travel to Boston, Massachusetts, to present her research on COVID-19 at a scientific conference on infectious disease. She credits her NIH mentors and IRP peers with helping her develop the scientific and social skills needed to bring her research to a wider audience.

“My experience as a postbac continues to be nothing but extraordinary,” she says. “Outside of conducting novel research, I gained a network of friends working hard to become future scientists and physicians. I am grateful to have gained lifelong mentors, who support my goal of becoming a physician. Moreover, each day at the NIH, I am learning how to effectively communicate my scientific findings, which is a skill that I hope to transfer into my future career as a physician.”

Fun fact: Kiana started competing in track and field competitions at the age of 10 and competed all four years of college in the long jump and triple jump at the Division I level. She was also named captain of her university’s 2021-2022 women’s track and field team and received Mississippi’s David M. Halbrook Award for Academic Achievements Among Athletes.

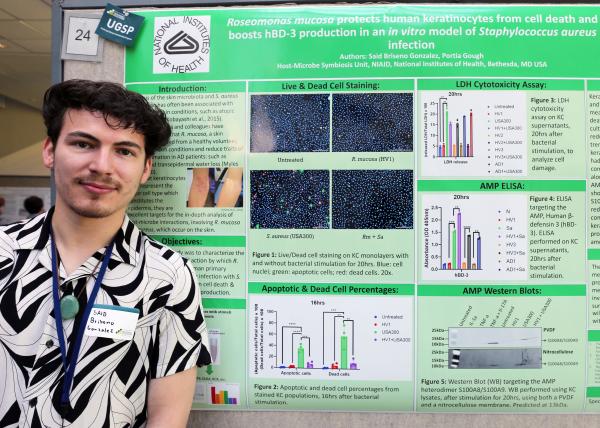

Said Briseno Gonzalez: Battling Skin Infections with a Beneficial Bacterium

Between his undergraduate research at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and the two years he has now spent at NIH as a postbac, Said’s scientific experiences have managed to cover a wide swath of the diversity that exists among living things. Said, who was the first person in his family to attend college, says he’s “always been fascinated by the complex processes of nature,” a fascination he sought to feed when he decided to spend some time as an undergraduate working in a lab focused on plant biology. Upon coming to NIH nearly two years ago, his research focus shifted to how the tiny bacteria living on our skin — known as the skin ‘microbiome’ — influence human health.

“I want to further my understanding about microbe-host interactions that take place in humans,” he says. “To me, this is important because new therapies and new vaccines can be developed from this understanding to combat emerging diseases.”

Along with his colleagues in the lab of IRP Independent Research Scholar Portia Gough, Ph.D., Said has been investigating how a type of bacteria called Roseomonas mucosa protects skin cells called keratinocytes from the ravages of the dangerous, antibiotic-resistant skin infection known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). His experiments have confirmed that R. mucosa helps keep keratinocytes, the most common type of cell in skin, from being killed by a MRSA infection. Importantly, he has also discovered that R. mucosa does this by increasing the amount of an antimicrobial substance that keratinocytes produce when they are exposed to the bacteria that cause MRSA.

“Not only do these findings help researchers understand the skin microbiota better, but we can also come to understand the cellular processes by which R. mucosa protects human keratinocytes,” he explains. “The implications of these findings are important because they provide insight into the potential mechanisms behind the therapeutic effects that R. mucosa can provide to patients who suffer from inflammatory skin diseases, such as eczema, or from MRSA skin infections.”

As a participant in NIH’s Undergraduate Scholarship Program (UGSP), Said had already benefited from NIH’s desire to nurture budding scientists even before he started as a postbac. The UGSP provides students from disadvantaged backgrounds with scholarships to partially fund their undergraduate educations in return for spending summers and at least a year after graduation doing research in an IRP lab. Those summer research experiences surely set him up to get the most out of the not one but two years he has now spent working full-time at NIH following graduation, which have seen him interact with many skilled and passionate colleagues both inside and outside the lab. His favorite part of his time at NIH, though, has been the opportunity he has had to give back to the IRP community through his role as the co-chair of the Health and Wellness Subcommittee on NIH’s Postbac Committee, where he has “learned many leadership skills” as he has worked to “equip other postbacs with the tools they need to lead healthy lives as they advance through their rigorous career paths," he says.

“My experience as a postbac at NIH has been very meaningful because I have been able to forge strong connections while training to become a better researcher,” he adds. “I was mentored by experienced investigators and learned several new lab techniques, and I involved myself in important affinity groups at NIH to support and receive support from my peers.”

Fun fact: Said loves to hike and spend time in nature, and he is occasionally accompanied by his dog, a mix between a golden retriever and a poodle known as a ‘golden doodle.’

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, May 20, 2024