Fighting the Fungus Among Us

Overactive Immune Response Sets Stage for Infection

IRP research has led to critical insights that might one day improve treatment for fungal infections that range from the merely annoying to the life-threatening.

Fungal infections are a serious medical threat to many people, especially those who are critically ill or have weakened immune systems. What’s more, outbreaks are on the rise, as studies show that rising global temperatures are causing fungi to evolve into new strains and grow in regions that were once too cold for comfort. Recent outbreaks include a tragic incident at a Michigan paper mill that sickened nearly 100 people and caused one death, as well as a cluster of fungal infections that have killed at least seven women who underwent cosmetic surgery at clinics in Mexico.

Commemorating Fungal Disease Awareness Week this week brings attention to the importance of combating fungal threats to our well-being. The theme this year is ‘Think Fungus,’ and that’s exactly what IRP senior investigator Michail Lionakis, M.D., Sc.D., has been doing for the last 20 years.

“Although we have co-evolved with fungi over millions of years, fungal infections have really emerged over the last few decades as a major problem in susceptible patients,” Dr. Lionakis says. That increase began with the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s, when ‘opportunistic’ fungal infections began breaking out in people whose immune systems had been devastated by HIV.

People receiving chemotherapy to treat cancer are among the many groups of patients who are highly vulnerable to fungal infections.

“Since then, we’ve gotten much better at treating many diseases such as cancer, autoimmune diseases, or organ failure with transplantation,” Dr. Lionakis continues. “That means there are more people living with compromised immune systems who are at risk for opportunistic fungal infections.”

While the incidence of fungal infections is rising sharply, the variety and quality of diagnostic tests lag behind. Moreover, even though treatments are better than they were 30 years ago at the height of the AIDS epidemic, the options are still pretty limited, their effectiveness is often disappointing, and they can be nearly as toxic to patients as they are to the fungi they are designed to kill. As a result, infections with assorted strains of fungi remain highly lethal among susceptible patients. Even with the best therapies available, death rates can reach up to 40 or even 60 percent, depending on the infection and type of patient. Dr. Lionakis hopes his research can improve those dismal statistics.

“My interest through the years has been how to better understand the immune defects that make people more susceptible to these infections,” Dr. Lionakis says. “And on the flip side, what do our immune systems do well to defend against fungal infections?”

A critical component of the work in Dr. Lionakis’ lab relies on seeing patients at the NIH Clinical Center with unusual susceptibilities to fungal infections, either because they have a rare genetic disorder that affects their immune system or they are on immunosuppressive drugs to treat other conditions. One of the rare diseases the group studies, called Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy–Candidiasis–Ectodermal Dystrophy, or APECED for short, revealed a surprising secret that could change the way doctors treat certain fungal infections.1

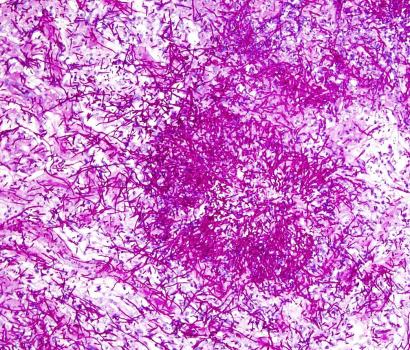

Close-up image of Candida albicans, the variety of fungus that commonly infects the mucus membranes of people with APECED.

APECED is caused by mutations in a gene called AIRE and causes patients’ immune systems to attack their own tissues. These patients also tend to develop chronic yeast infections of the mucous membranes, such as the ones lining the mouth and throat. To learn more about why, Dr. Lionakis and his colleagues gathered the world’s largest group of APECED patients at NIH.

“We came to realize that in this particular disease and mucosal fungal infection, susceptibility is actually driven, surprisingly, not by an inability of the immune system to fight off the fungus, but instead by an excessive immune response which damages the mucosal tissue and leaves it exposed to colonization and invasion by the fungus,” Dr. Lionakis says.

Before this discovery, the common assumption was that the AIRE mutations behind APECED short-circuited the protective immune response against the fungus initiated by cells called T helper 17 cells. Dr. Lionakis and his team, however, found that the reaction led by those cells worked normally in both mice that lacked the AIRE gene and in APECED patients. Instead, the scientists discovered that other varieties of T cells in patients’ mucous membranes were inadvertently participating in a sabotage effort by overproducing a molecule called interferon gamma (IFN-gamma). When produced in normal amounts, IFN-gamma is an important tool in the arsenal against bacteria, viruses, and fungi, but in people with APECED, excessive IFN-gamma levels damage the protective barrier formed by the mucus membranes, allowing the fungus to take root more easily.

When the IRP researchers subsequently short-circuited the effects triggered by IFN-gamma in mice using an FDA-approved medication, they found the intervention reduced fungal disease. What’s more, since publishing the results of that study, they have also found that patients with APECED have a similar excess of IFN-gamma in multiple other types of tissue that are affected by their over-active immune systems, such as their hormone-releasing ‘endocrine’ tissues. Dr. Lionakis’ team is now recruiting patients for formal clinical trials at NIH that will test whether suppressing IFN-gamma is an effective treatment for the fungal infections and other symptoms experienced by people with APECED.

Dr. Michail Lionakis

“Not only have we uncovered what I would call a paradigm shift in how we think about infections — that they can be caused by an excessive immune response rather than something lacking from our immune response — but we now have a potential drug therapy for these patients,” he says.

While he works on that clinical trial, Dr. Lionakis hopes to also determine whether that same problem with excess IFN-gamma may be at play in other rare disorders caused by mutations in single genes, and even perhaps in some common diseases that involve untethered immune responses or excessive inflammation. If that’s the case — and preliminary data suggests it is — then tamping down the release of IFN-gamma or blocking its effects could help treat not only annoying, common fungal infections, but also improve the lives of people with autoimmune conditions that predispose them to severe fungal disease.

“It has been a remarkable journey for all of us because we can help the patients and we are learning a lot in the process,” Dr. Lionakis says. “When you make discoveries that can actually lead to formal treatment trials and hopefully benefit patients, it’s very humbling for all of us.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Break TJ, Oikonomou V, Dutzan N, Desai JV, Swidergall M, Freiwald T, Chauss D, Harrison OJ, Alejo J, Williams DW, Pittaluga S, Lee CR, Bouladoux N, Swamydas M, Hoffman KW, Greenwell-Wild T, Bruno VM, Rosen LB, Lwin W, Renteria A, Pontejo SM, Shannon JP, Myles IA, Olbrich P, Ferré EMN, Schmitt M, Martin D., Genomics and Computational Biology Core, Barber DL, Solis NV, Notarangelo LD, Serreze DV, Matsumoto M, Hickman HD, Murphy PM, Anderson MS, Lim JK, Holland SM, Filler SG, Afzali B, Belkaid Y, Moutsopoulos NM, Lionakis MS. Aberrant type 1 immunity drives susceptibility to mucosal fungal infections. Science. 2021 Jan 15;371(6526):eaay5731. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5731.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, September 20, 2023