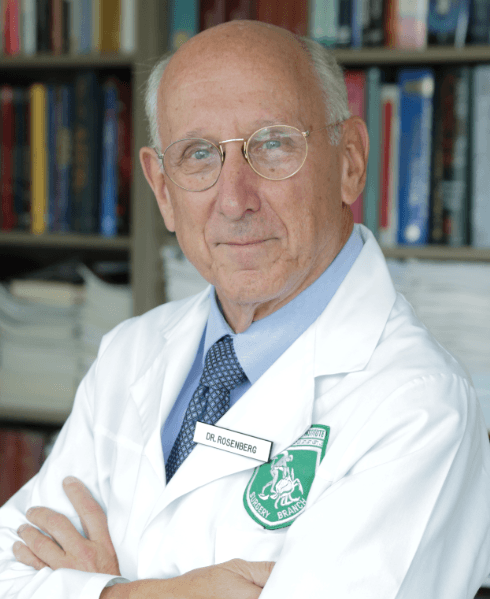

IRP’s Steven Rosenberg Receives HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service

Groundbreaking Immunotherapy Research Revolutionizes Cancer Treatment

IRP senior investigator Steven A. Rosenberg received the HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service in recognition of his pioneering contributions to the development of cutting-edge cancer therapies.

Like many young boys, IRP senior investigator Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., initially believed he would grow up to become a cowboy, a dream he shared with his older brother, Jerry. That plan changed after World War II ended and stories began coming out of Europe about members of his family who had perished in concentration camps.

“I just became so upset about the evil that people could perpetrate on one another,” he recalls. “Right then and there, I knew I wanted to do the opposite. I wanted to do things that would help people, and I developed almost a spiritual desire to become a doctor.”

He ultimately did become a doctor, and his pioneering research into how cancer interacts with the immune system has led to treatments that are reducing suffering for many people with cancer. In recognition of this groundbreaking work, Dr. Rosenberg was awarded the HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service in August 2021. The highest honor given by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the award celebrates excellence in leadership, ability, and service.

Over his 47 years as Chief of Surgery at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), Dr. Rosenberg has been at the forefront of using immunotherapy and gene therapy to treat multiple forms of cancer, including kidney cancer, lymphoma, and melanoma. These treatments target tumors directly, avoiding the collateral damage caused by surgery, traditional chemotherapy, and radiation, all of which remove or destroy healthy tissue along with the tumor. The therapies based on Dr. Rosenberg’s work have even proven capable of combating ‘metastatic’ cancers that have already spread around the body from the site where they first developed.

“Even though I’m a surgeon, virtually everything I’ve done in my career has been aimed at developing new approaches that don’t use scalpels, chemotherapy drugs, or radiation beams,” Dr. Rosenberg says.

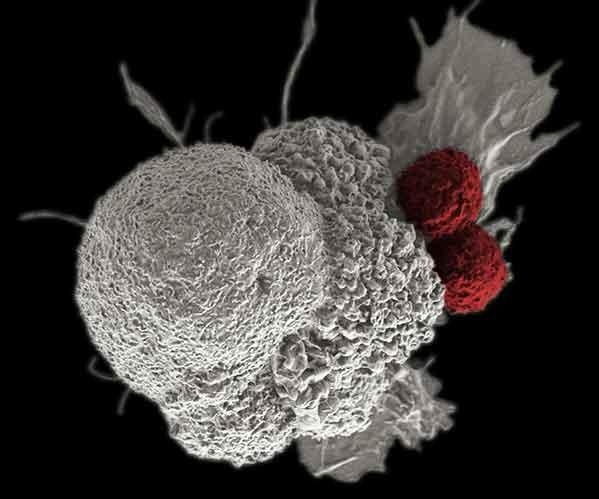

Immune cells (red) attacking a cancer cell (white) as part of a natural immune response. Cancer immunotherapy aims to help immune cells do this more effectively.

Cancers emerge due to changes in healthy cells, but they still resemble normal cells closely enough that the immune system usually fails to recognize them as a threat. The goal of immunotherapy is to beef up the body’s own response so that it attacks and controls tumors.

“One of the major advantages of immunotherapy is it can be highly specific in its recognition of affected cells,” Dr. Rosenberg explains. “The hope is that we can develop curative treatments for cancer that do not involve the destruction of any normal tissue and will have minimal side effects.”

As a young surgical resident at what is now Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Dr. Rosenberg was assigned to work at the VA Hospital in the neighborhood of West Roxbury. There, he encountered a patient who needed his gallbladder removed, but a quick review of the patient’s medical records showed something very unusual. Twelve years earlier, the patient had undergone surgery to remove a stomach tumor. The notes indicated that several tumors couldn’t be removed, and the patient had received no further treatment. Yet when Dr. Rosenberg performed the gallbladder surgery, there was no sign of the old cancer.

“It’s one of the rarest events in medicine,” Dr. Rosenberg says. “Somehow his body had learned to defeat the disease, and it seemed likely to me that the immune system was responsible.”

Even though the disappearance of cancer without treatment is extremely rare, Dr. Rosenberg saw another similarly intriguing case as a medical resident. A patient had received a donated kidney that his doctors later learned contained cancerous cells. With the patient’s immune system disabled so his body would not reject the new kidney, the cancer quickly spread. When his doctors stopped the immunosuppressive drugs, his body rejected the kidney as expected, but much to their surprise, the patient’s body also started attacking the cancer — even cancer cells that had spread from the donated organ.

"That demonstrated to me that if you have a strong enough immune stimulus, the body was capable of rejecting even large, invasive cancers," Dr. Rosenberg explains.

Photo courtesy of NCI

Dr. Rosenberg with a patient in 1984.

When Dr. Rosenberg joined NIH in 1974, many oncologists thought that immunotherapy against cancer would be impossible. However, he and his colleagues began a series of studies to prove that claim wrong. They focused on immune cells called lymphocytes, which are white blood cells that fight infection.

After many starts and stops, they eventually determined they could remove lymphocytes that had infiltrated the tumor — and were therefore already fighting the cancer — and treat the extracted cells in in the lab with a hormone naturally produced in the body called interleukin-2 (IL-2), which stimulated them to multiply 1,000-fold. These lymphocytes, the researchers discovered, could then be injected back into the patient, where they found their way to the tumor and stepped up their attack.

“This concept of using the body’s own immune cells as a drug has been the underlying basis of virtually everything I’ve done,” Dr. Rosenberg says.

The first immunotherapies approved for cancer treatment were based on Dr. Rosenberg’s research with IL-2. In 1985, his team showed that giving patients that hormone could cause tumors to shrink in about 20 percent of people with melanoma and metastatic kidney cancer. Moreover, among the group that responded to the IL-2 treatment, about one-third showed no signs of cancer afterwards. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved IL-2 immunotherapy for kidney cancer in 1992 and for melanoma in 1998. Since then, Dr. Rosenberg’s team has been improving the treatment and applying it to other cancers, including blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma.

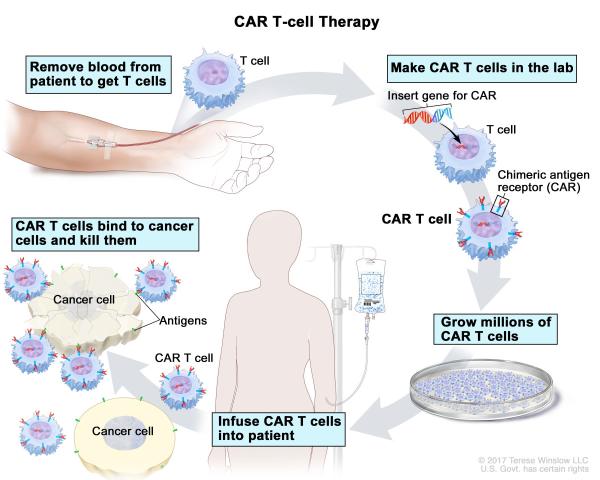

Diagram showing the process behind CAR T-cell therapy, one of the cancer treatments that Dr. Rosenberg has helped develop over the course of his career.

More recently, Dr. Rosenberg and his team have been developing gene therapies that modify patient’s own immune cells so that they can more effectively recognize and attack cancer. This work led to the 2017 FDA approval of the first-ever gene therapy for cancer. In addition, by studying the cancers of more than 200 patients, Dr. Rosenberg’s team has identified hundreds of unique chemical tags, called antigens, on cancer cells that immune cells could potentially use to identify and attack those harmful cells. This work will be important for developing more personalized gene therapies for cancer, since the treatments would require knowing the exact molecular nature of a patient’s disease. Dr. Rosenberg’s team is now working on ways to efficiently produce the modified immune cells needed for such treatments.

“These antigens are unique to each individual, so targeting them has to be highly personalized,” he says.

For Dr. Rosenberg, receiving the HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service is more than an acknowledgement of nearly 50 years of achievement. He also sees it as a motivator.

“This award is a recognition not only of what I've done,” Dr. Rosenberg says, “but also an indication and inspiration to continue to make progress toward the goal of developing new immunotherapies for patients with cancer.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024