IRP’s Charles Rotimi Elected to American Academy of Arts and Sciences

Pioneering Genetic Epidemiologist Takes a Global Approach to Fighting Health Disparities

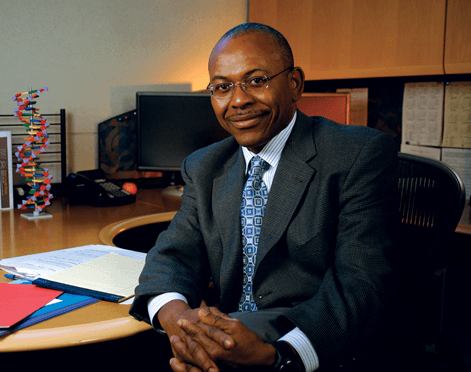

Dr. Charles Rotimi was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences earlier this year for his research and leadership efforts to reduce health disparities in African populations.

IRP distinguished investigator Charles Rotimi, Ph.D., was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences this year in recognition of his pioneering work exploring the health implications of genetic diversity in populations with African ancestry, as well as for globalizing the study of genomics, particularly in African nations. Dr. Rotimi joined NIH in 2008 as the founding director of the Intramural Center for Genomics and Health Disparities in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), which was later renamed the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health, in part to reflect Dr. Rotimi’s globe-spanning research programs.

“I've always been passionate about making sure that biomedical research, specifically genomic research, is applied to our global populations,” Dr. Rotimi says. “Whether we are deploying technology or training people, we should be looking at it from a global context so that we don’t exacerbate inequalities that already exist.”

When Dr. Rotimi arrived in the U.S. from Nigeria in 1982 to pursue a Master’s degree at the University of Mississippi, he quickly realized deep health disparities existed between populations in the United States, especially between African Americans and other groups. Ever since, he has devoted his career to understanding how the genetic, environmental, social, and cultural factors involved in metabolic diseases such as diabetes interact to affect health. Dr. Rotimi’s research is particularly motivated by a desire to understand how the genetic differences that emerged in geographically separated groups of humans during our evolutionary history influence health.

Due to a combination of genetic, environmental, and other factors, African Americans have higher rates of obesity, heart disease, and diabetes than other groups in the U.S.

“I’ve always been fascinated by the human history of how we share much of our heritage as human beings, but also the differences that we’ve developed to help us adapt to different environments,” he says.

Dr. Rotimi began his career in epidemiology soon after finishing his Ph.D. studies at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. While working in Alzheimer’s disease research as a postdoctoral fellow, he noticed an advertisement for an assistant professorship in epidemiology at Chicago’s Loyola University Medical Center. The ad seemed as if it had been written especially for him, and he immediately called the department head. He ultimately got the job and, in 1992, joined a Loyola University lab that investigated why rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity vary across populations of African ancestry in West Africa, the U.S. and the Caribbean.

Meanwhile, the Human Genome Project was making it possible for the first time to pinpoint the locations of genes involved in specific diseases. Soon after the first successes in mapping the human genome were announced in 2001, it became clear to Dr. Rotimi and many others in the genetics field that the next step would be to compare and understand how certain genes differ between different populations. This realization led to the development of the International HapMap project, which collected genetic samples from people across the globe and systematically documented variations in key areas of their genomes.

More From the IRP

Podcast

Dr. Anna Nápoles — A New Dawn for Minority Health

Dr. Rotimi, who had since moved to Howard University in Washington, D.C., became the principal investigator for the HapMap researchers’ collection efforts in three African communities in Nigeria and Kenya. Africa, he points out, is where human history began, and therefore where we could expect to find the oldest and most varied genetic profiles.

“For me, this work was really important to do because we wanted to make sure that we are indeed representing the huge genetic variation across African populations,” Dr. Rotimi says.

By analyzing the genomes of large numbers of people from around the world, scientists like Dr. Rotimi can discover genetic variants that explain why some populations are more or less likely to develop certain diseases.

In 2003, Dr. Rotimi became the founding president of the African Society of Human Genetics (AfSHG), a group designed to engage African geneticists and researchers in a forum where they could meet, share ideas, and address issues of significance to them. Without such an organization, the Society’s founders worried, the genomic revolution might “fly over Africa like a lot of previous scientific revolutions had,” Dr. Rotimi explains.

Dr. Rotimi and AfSHG did more than provide a forum for researchers to connect, however. In 2009, the organization spearheaded an initiative called the Human Heredity & Health Africa (H3Africa) Initiative, sponsored by NIH and the Wellcome Trust. This project has provided more than $180 million to fund the development of infrastructure to support African-led genomics research, including funds for training scientists and building cutting-edge laboratories.

“As somebody who grew up in Nigeria and studied biochemistry there, I couldn't do my work because there were no good laboratories for me,” Dr. Rotimi says. “In H3Africa, I was extremely sensitive to the fact that we should specifically train African scientists so they don’t have to travel abroad to work.”

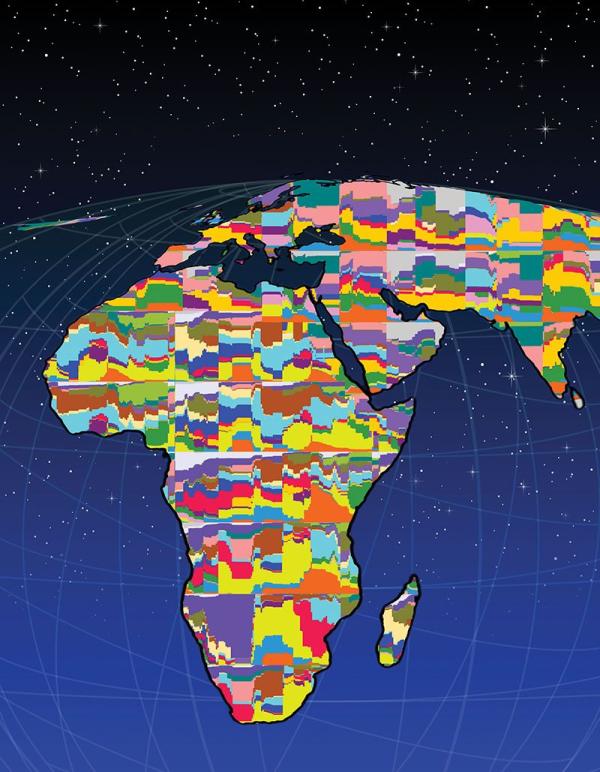

Image credit: Noah Rosenberg and Martin Soave, University of Michigan

Africa may be the most genetically diverse area in the world, as shown in this map of global human genetic variation.

Today, under Dr. Rotimi’s leadership, NHGRI’s Intramural Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health is continuing its work collaborating with global researchers to study disease-associated genetic variations in populations around the world, including in Africa, Asia, and South America. His own lab at NIH also follows this theme. For example, his team recently published research that used data from the long-standing Africa America Diabetes Mellitus (AADM) study to identify genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes in more than 5,000 people living in Kenya, Nigeria, and Ghana. The study identified a gene involved in DNA replication and repair and showed that it is also important to ensuring the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas work properly. Insulin release is key to managing blood sugar levels in people with diabetes, and Dr. Rotimi’s team identified a variant of the gene that causes loss of beta cells and impairs surviving beta cells’ ability to produce insulin in response to high sugar levels, thereby increasing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The variant had not been found earlier because it is extremely rare in non-African populations.

Just as his research includes people from all parts of the globe, Dr. Rotimi has also brought the world to his lab. He takes great pride in training and engaging postdoctoral fellows from many different countries who bring a wide variety of perspectives and ideas to his team.

“This is really the best laboratory in terms of cultural and scientific background and the kind of questions that we ask,” says Dr. Rotimi. “That to me is very refreshing.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024