Duo Delves Into Genetics of Diabetes

Drs. Leslie Baier and Robert Hanson Identify Genetic Risk Factors in American Indians

A team of researchers at NIH’s campus in Phoenix, Arizona, is working with the local American Indian community to learn about genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes.

November is both Diabetes Awareness Month and Native American Heritage Month. Unfortunately, the month of November is not the only link between Indigenous populations and diabetes. Members of minority groups have a much higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes and its many complications compared to the general population, and this is especially true of some American Indian tribes, whose members are twice as likely to have type 2 diabetes as white Americans.

At the Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch in Arizona, part of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), IRP senior investigators Leslie J. Baier, Ph.D., and Robert Hanson, M.D., M.P.H., are working to understand why American Indians living in the southwestern U.S. are disproportionately affected by type 2 diabetes and obesity. Using family histories, medical records, and other data collected during a decades-long study of these communities, combined with extensive analysis of some of their participants’ DNA, their team has identified several genes that contribute to risk for those two conditions, along with some surprising findings about their prevalence.

“The surprising thing is there isn’t one common gene mutation or variant carried by this population of American Indians that can account for all the diabetes in the population,” Dr. Baier says. “I don’t think any of us dreamed this would be the case.”

In fact, they discovered that hundreds of genetic variations contribute to a person’s risk for developing diabetes and obesity, and many of them are common across ethnic groups. Each variant by itself has only a small influence, but these weak effects add up such that the more risk variants a person has, the greater his or her risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

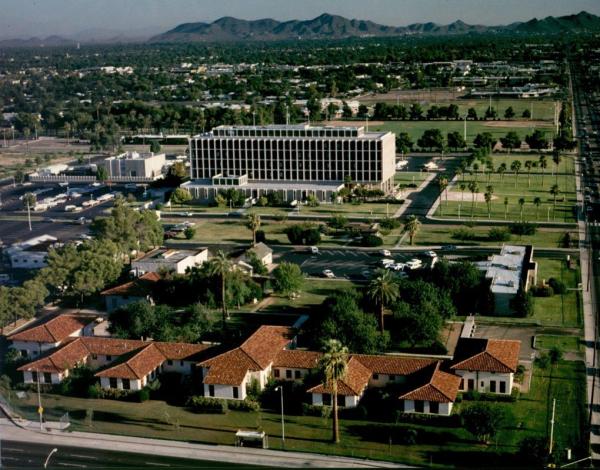

Drs. Baier and Hanson perform their research at NIH’s Phoenix Epidemiology and Clinical Research Branch (PECRB), pictured here.

However, Dr. Baier and Dr. Hanson also found a few exceptions to these rules. Some gene variations that are strong determinants of diabetes risk in white populations have only a mild influence on risk among southwestern American Indians. At the same time, the IRP scientists have also found several less common gene variants that are completely unique to the American Indian community they work with, and these variants have large effects when they are present. Intriguingly, the variant that appears to have the greatest impact on diabetes risk in that population is one that takes effect only when it is inherited from the mother. This type of gene is silenced when it comes from the father, a phenomenon called imprinting.

“This is something we wouldn’t have understood 20 years ago, even if we had the technology to detect this variant, because so little was known about imprinting and silencing of genes,” Dr. Baier says. “I think as our knowledge is expanding, we’re understanding this disease a lot more.”

Dr. Baier and Dr. Hanson have also identified several genetic variations that increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes at a young age. For example, their research group was the first to show that children whose mothers are diabetic while pregnant have a very high risk for developing type 2 diabetes. They also identified a gene variant that causes children to become overweight or obese very early in life, leading to very-early onset type 2 diabetes. In fact, they have seen children in the southwestern Indigenous community develop type 2 diabetes as young as age 4.

Dr. Leslie Baier

“The strange thing is we don’t see any type 1 diabetes in these kids,” says Dr. Baier. “It’s exclusively type 2.”

Studying the genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes is vital to developing better prevention and treatment strategies, both for American Indians and for the wider population. Although type 2 diabetes does not affect every person in identical ways, currently available drugs use a one-size-fits-all approach. Identifying genetic differences that increase risk for the condition will allow development of more specific drugs and enable physicians to select the therapy that is best-suited for each patient.

“I hope this research will lead us to new disease pathways and new drug targets,” says Dr. Baier. “That has already proven to be true. Some genetic variants that were discovered years ago have become very effective drug targets. This is true even when the gene’s actual contribution to diabetes risk is comparatively small.”

Today, Dr. Baier and Dr. Hanson are trying to better understand how the genetic variations they have identified influence risk for type 2 diabetes. For this work, they rely on blood samples from American Indian volunteers whose clinical histories and genetic profiles are known. The researchers use the blood to create induced pluripotent stem cells, a variety of cell that can turn into any other type of cell. They then coax those stem cells to mature into the insulin-producing islet cells found in the pancreas, since it is these cells’ inability to produce sufficient insulin that is partly responsible for the health consequences of type 2 diabetes. By observing the growth and maturation of these cells in the lab, the scientists can watch how different genetic variations affect their development and, ultimately, their ability to produce insulin.

Of course, factors beyond genetics can also increase risk for type 2 diabetes. As with genes affecting almost any trait, those related to type 2 diabetes interact with a person’s lifestyle habits and life circumstances, making it important to understand both.

Dr. Robert Hanson

“We’re moving to integrate genomic information with other aspects of biology and the social environment to try to understand why someone may get diabetes and what is the best way to prevent that from happening,” says Dr. Hanson.

Beyond conducting experimental science, Dr. Baier and Dr. Hanson are also trying to recruit and train more American Indians from the population they work with to become directly involved in research, such as by encouraging young community members to pursue scientific careers of their own. In fact, Dr. Baier notes that two students whose families have volunteered for her studies over the decades recently worked in her lab and are now pursuing advanced degrees — one is in medical school and another just finished his doctoral studies.

“Although the identity of each individual sample is confidential, it was cool to know that their grandparents were among the thousands of samples they were studying while working here,” Dr. Baier says. “I think part of the future of research will have more people from this community involved in making decisions, helping with their own health care, and advancing the science. That’s something our branch has been working very hard to make happen.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023