A Sweet Treatment for Diabetes

Sugar Molecule Protects Mice Against Type 1 Diabetes

Ingesting too much sugar is usually problematic for patients with type 1 diabetes, but surprising findings from an IRP study suggest a particular form of sugar could actually be a boon for these patients.

Avoiding too much sugar is one of the cardinal rules for those who have or are at risk for diabetes. In fact, diabetes is characterized by having too much glucose, a form of sugar, in the blood. As a result, it came as quite a surprise to IRP researchers led by senior investigator Wanjun Chen, M.D., when they discovered that a particular form of sugar that they expected to have no effect on diabetes-prone mice actually protected them from developing type 1 diabetes.1,2

Each November, Diabetes Awareness Month recognizes the millions of Americans living with type 1 diabetes or its close cousin, type 2 or ‘adult onset’ diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder in which the body’s own immune system attacks the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. The hormone insulin is necessary for cells to turn the sugars in the food we eat into energy. Without insulin, sugar will build up in the bloodstream, causing inflammation and organ damage. There is no cure for type 1 diabetes, and people with the condition must inject or infuse insulin every day to maintain a safe and healthy level of the hormone, which can be inconvenient and expensive.

One of the common problems seen in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes is an increased risk of infection, due in part to a weakened immune system. In 2017, Dr. Chen’s group published the surprising results of a series of experiments designed to test whether high levels of blood glucose might suppress the immune system. The researchers treated mouse immune cells growing in petri dishes with glucose, which they theorized might trigger increased replication of regulatory T cells, an anti-inflammatory variety of immune cell that tamps down the immune response. The scientists also treated another set of immune cells with a different sugar called D-mannose as a ‘control’ for comparison because they expected the sugar to have no effect on the cells.

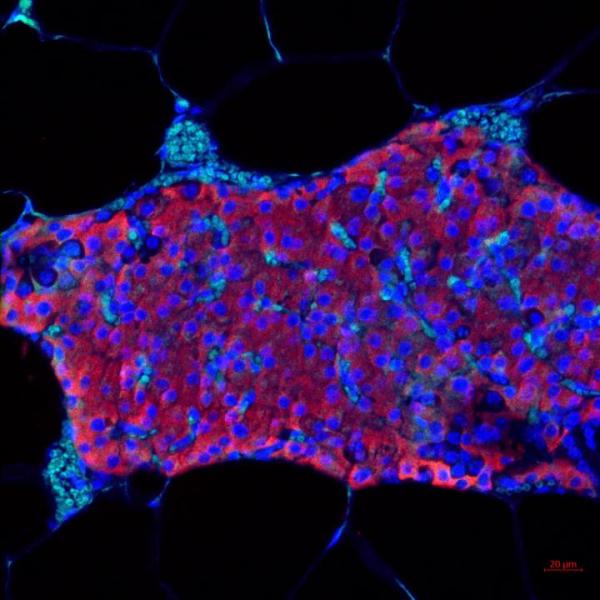

Image credit: Maria Coronel, Georgia Tech

Pancreatic islets, which contain the insulin-secreting beta cells that are destroyed in people with type 1 diabetes.

The results of their experiment completely defied their expectations. While the glucose had no effect, an increased number of the control cells treated with D-mannose developed into regulatory T cells. Since an overzealous immune response that destroys insulin-secreting cells is a key cause of type 1 diabetes, the discovery suggested that D-mannose could actually be protective against the disease. What’s more, because of the specific mechanism by which D-mannose affects regulatory T cells, using the sugar to stave off type 1 diabetes is unlikely to suppress the immune system in the way Dr. Chen’s team thought glucose might.

“We did not believe it at the beginning,” says Dr. Chen. “Ultimately, we had to accept the results because our postdoctoral fellow repeated the experiment several times and, every time, he got the same result.”

The researchers originally selected d-mannose simply because it is very similar to glucose in both size and molecular weight, but with a different molecular structure. However, their surprising findings spurred them to learn more about it. It turned out that D-mannose is an important sugar involved in many different chemical reactions in the body. Moreover, like glucose, it can be found in the bloodstream, though at much lower levels. It is also abundant in certain vegetables and fruits, such as cranberries, and it is sold as a supplement in many stores, often as a treatment for urinary tract infections.

More From the IRP

Blog Post

Cellular Self-Destruct Tied to Type 2 Diabetes

Although the mechanism behind its protective qualities is not very well understood, researchers suspect d-mannose prevents bacteria from sticking to the walls of the urinary tract, causing them to be flushed out of the body. There was almost nothing in the scientific literature, however, about the relationship between d-mannose and the immune system. To learn more, Dr. Chen and his colleagues decided to give the sugar to a variety of mice that typically develop diabetes by 12 weeks of age. While 90 percent of the mice that drank normal water developed type 1 diabetes by the age of 12 weeks, most of the animals that drank water sweetened with D-mannose remained healthy even at 23 weeks of age. Meanwhile, although D-mannose did not reverse diabetes in mice that had already developed the condition, it did help lower their blood sugar, ameliorating a key symptom of the disease.

Dr. Wanjun Chen

“This was also surprising because the d-mannose not only prevented diabetes, but it also actually can stabilize blood sugar,” says Dr. Chen. “While the diabetic mice weren’t cured, their blood sugar stopped rising.”

Since the publication of these experiments in Nature Medicine in 2017, Dr. Chen’s group has continued to study D-mannose. For example, the IRP scientists have shown that D-mannose can play a role in suppressing obesity, which is particularly important in controlling type 2 diabetes. The researchers theorize that D-mannose may help reduce inflammation, thereby preventing fat cells from expanding and contributing to weight gain. It is also possible that D-mannose helps correct an imbalance of the bacteria in the digestive tract, known as the gut microbiome, that is observed in people with obesity. This imbalance can lead to problems with the way fat cells process and store nutrients. However, more research is needed to better understand the relationships between the immune system, the gut microbiome, and obesity.

“The more studies we have now, the more confident we feel,” says Dr. Chen. “I really hope that someday we can do something for patients. That’s my dream.”

At some point in the future, his team would like to do clinical studies in humans to test whether d-mannose can help with obesity, possibly in collaboration with physicians in the NIH’s National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). In fact, access to colleagues across the IRP is one of the aspects Dr. Chen particularly appreciates about working at the NIH, where he has been since 1997.

“You have this space to collaborate among the different disciplines,” he says. “If you want to study genetics, or epigenetics, or some kind of animal, there are people who can share and help each other. I think this is very important for the Intramural program and unique to the NIH.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References

[1] D-mannose induces regulatory T cells and suppresses immunopathology. Zhang D, Chia C, Jiao X, Jin W, Kasagi S, Wu R, Konkel JE, Nakatsukasa H, Zanvit P, Goldberg N, Chen Q, Sun L, Chen ZJ, Chen W. Nature Med. 2017 Sep; 23(9):1036-1045. Doi:10.1038/nm.4375. Epub 2017 Jul 24.

[2] A sweet deal for diabetes. Villa M, Qiu J, Pearce EL. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2018 Jan; 29(1):1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2017.10.006.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023