Scientists Pinpoint Traitorous Immune Cells in Lupus

Narrower Research Focus Could Aid Treatment for Autoimmune Diseases

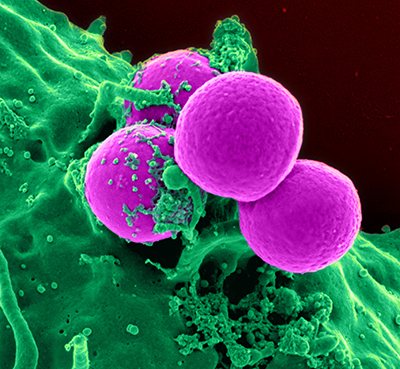

Immune cells called neutrophils (green, shown here engulfing bacteria) attack the body’s own cells in individuals with autoimmune diseases like lupus. New IRP research has narrowed down the specific type of neutrophil that damages the body in lupus patients.

Police pursuing a dangerous criminal rely on witness descriptions of the suspect’s specific traits — height, weight, hair color, tattoos — to pick out the perpetrator from a vast population of mostly innocent individuals. Scientists can likewise distinguish between highly similar cell types using cutting-edge laboratory procedures. Using such techniques, IRP researchers have identified a particular variety of cell in a specific stage of its life cycle as a primary culprit behind the autoimmune disease known as lupus.1

In autoimmune diseases, the immune system attacks the body’s own cells in the same way it wages war with harmful invaders like bacteria. In addition to experiencing symptoms like pain, fatigue, and rashes, lupus patients are also highly prone to developing cardiovascular disease. While treatments that broadly suppress the immune system can alleviate symptoms, they leave patients vulnerable to the infections that our immune systems protect us against.

Years of research on the immune systems of people with lupus eventually revealed that cells called neutrophils, the immune system’s ‘first responders,’ wreak havoc in these patients’ bodies. Researchers led by IRP senior investigator Mariana Kaplan, M.D., subsequently discovered that some neutrophils in the blood of lupus patients behave very differently from typical neutrophils. Importantly, her lab found that these cells, which they dubbed ‘low-density granulocytes,’ or LDGs for short, can damage blood vessels.2 Not content to stop there, in their new study, Dr. Kaplan and her team set out to further narrow down which neutrophils harm the body in lupus.

“Over the last several years, there has really been an improvement in the technology we use to study immune cells, so it’s prime time for us to answer the question of whether neutrophils are really all the same and whether differences in neutrophil biology are responsible for some of the symptoms of lupus,” says Dr. Kaplan, the new study’s senior author.

By closely scrutinizing LDGs isolated from the blood of lupus patients and comparing them to normal neutrophils from the same patients and healthy individuals, the IRP team was able to identify two distinct subtypes of LDGs. While the activity of genes differed greatly between LDGs as a whole and normal neutrophils, the genes in a small subset of LDGs were much more active than in the rest of patients’ LDGs.

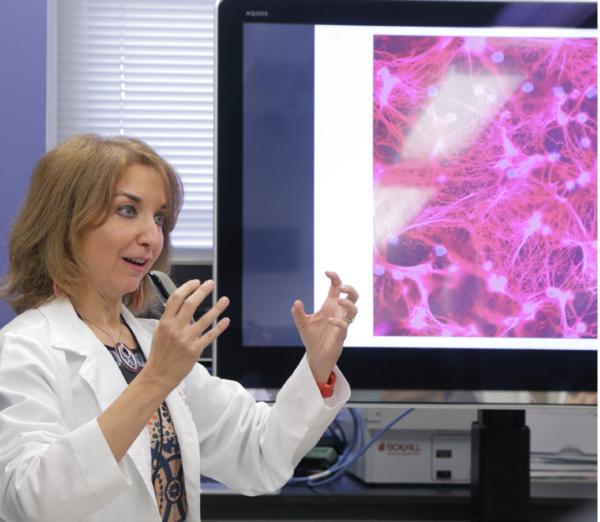

Dr. Mariana Kaplan, the new study’s senior author, discusses images of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), a key contributor to blood vessel damage in patients with lupus.

Further experiments revealed that the former, smaller group of LDGs lacked a molecule called CD10 on their surfaces, whereas the molecule was not missing in the latter, larger group of LDGs. This suggested that the neutrophils with a more active genetic signature were ‘immature,’ since CD10 is only found on ‘mature’ neutrophils that are in later stages of their life cycles and possess all of the abilities neutrophils use to fight infections. Indeed, the more mature, CD10-positive LDGs did a better job of engulfing bacteria, moving toward chemicals that signal injury or infection, and producing web-like structures called neutrophil extracellular traps that ensnare bacteria but can also harm patients’ tissues.

Finally, Dr. Kaplan’s team examined a separate set of lupus patients and found that higher numbers of CD10-positive, mature LDGs in their blood were associated with decreased kidney function and greater damage to blood vessels. Levels of CD10-negative, immature LDGs, on the other hand, were not correlated with these clinical measures, suggesting that the more mature LDGs are the ones involved in lupus symptoms, including patients’ high risk of cardiovascular disease.

“To this day, no drug we use to treat lupus has been shown to decrease the elevated risk for premature heart disease that lupus patients have,” Dr. Kaplan says. “I think trying to identify drugs that target specific neutrophil subsets could provide more selective therapies and finally allow clinicians to tackle the premature vascular disease that right now represents the number one cause of death in lupus patients. It also goes beyond lupus to other autoimmune diseases in which LDGs have been identified and premature cardiovascular disease is a main reason why patients get sick or die.”

The IRP team’s findings could also provide useful clinical biomarkers, as clinicians could more closely monitor or more aggressively treat patients with higher numbers of mature LDGs in their blood. Such an approach would be made even more beneficial if scientists could pinpoint the exact processes that make those cells harmful.

“That may point to a way that we can decrease the damage that these cells trigger,” Dr. Kaplan explains. “We may not be able to get rid of the cells themselves, but perhaps we can tamp down their abnormal behavior and return them to normal function.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Transcriptomic, epigenetic, and functional analyses implicate neutrophil diversity in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Mistry P, Nakabo S, O'Neil L, Goel RR, Jiang K, Carmona-Rivera C, Gupta S, Chan DW, Carlucci PM, Wang X, Naz F, Manna Z, Dey A, Mehta NN, Hasni S, Dell'Orso S, Gutierrez-Cruz G, Sun HW, Kaplan MJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019 Dec 10;116(50):25222-25228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908576116.

[2] A distinct subset of proinflammatory neutrophils isolated from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus induces vascular damage and synthesizes type I IFNs. Denny MF, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Thacker SG, Anderson M, Sandy AR, McCune WJ, Kaplan MJ. J Immunol. 2010 Mar 15;184(6):3284-97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902199.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023