Another Piece of the Alzheimer’s Puzzle

A Conversation with Dr. Lori Beason-Held

IRP staff scientist Dr. Lori Beason-Held

Expert estimates suggest that more than 5.5 million Americans may have dementia caused by Alzheimer’s, a disease currently ranked as the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States. Because of the condition’s growing prevalence and profound consequences for patients, understanding Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of cognitive decline is an important goal within the Intramural Research Program.

One example of the IRP’s many contributions to the field of Alzheimer’s research is a 2013 study that detected brain changes in older adults who would go on to develop cognitive impairment years before their memory began to fail. This research, led by IRP staff scientist Lori Beason-Held, Ph.D., aimed to understand who might be susceptible to developing Alzheimer’s disease and what factors contribute to the development of the disease before symptoms appear.

In recognition of June as Alzheimer’s and Brain Awareness Month, we sat down with Dr. Beason-Held to discuss that discovery, its implications for Alzheimer’s patients, and her continued research on how age-related diseases modify brain function.

What prompted you to conduct this research?

“I became a neuroscientist who studies aging for both personal and societal reasons. As a child I was fascinated by my older family members. To me they seemed to always have the answers to life’s problems, and their outlook on life was so different from mine. I thought they were brilliant.

“Because I had such great respect and admiration for older people, I began to pay attention to the issues and problems that arise as we get older. I saw that one of the biggest fears of the older generation was losing their ability to think and remember. This, above all else, has been a driving force in my career.

“I want to understand what leads to dementia in our older population. I want to help solve the puzzle of Alzheimer’s disease, so that older folks can lead long, productive lives that don’t end in confusion or loss of dignity. They deserve better than that.”

What impact has this research had to-date?

“The results of this study are just another piece of the Alzheimer’s puzzle. Over the past 10 years, it has become clear that to prevent Alzheimer’s, we need to stop the disease before the symptoms begin. In order to do that, we must figure out who is most likely to develop the disease in the future. That is a formidable challenge and I am fortunate to work in a lab that has the creative thinkers, resources and data to work on this problem.

“Our lab works with the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, also known as the BLSA, which is a study of natural aging that began in 1958. The participants in the study come in for a visit every year or two, which includes top-to-bottom health workups. From there, we oversee the neuroimaging component of the study. Due to the brain scans collected year after year, we were able to look back at brain changes that occurred before the participants developed cognitive problems.

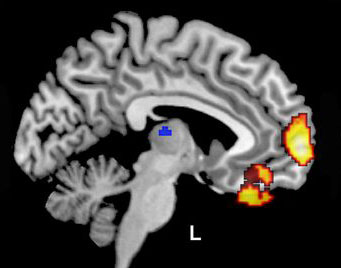

“In this case, we studied brain function and found that brain activity increases in the frontal lobe and decreases in the parietal and temporal lobes of the brain before the onset of cognitive decline. As these areas are involved in cognitive function and also accumulate pathology in Alzheimer’s disease, it is likely that these changes are a marker of future functional decline.”

Dr. Beason-Held and her collaborators used positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to examine the relationship between changes in blood flow in the brain and later cognitive decline.

What tools did you use to conduct this research?

“We used neuroimaging data from the BLSA. The BLSA is an incredibly valuable resource because without longitudinal studies of this nature, it wouldn’t be possible to go back in time and investigate changes that occur before the start of disease.

“In addition, because this study involved neuroimaging in Alzheimer’s disease, we collaborated with Drs. Michael Kraut and Richard O’Brien from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for their expertise in imaging and Alzheimer’s disease characteristics and diagnosis.”

What was the most challenging aspect of this research?

“The most challenging aspect of this study is our current limitation in predicting who will develop Alzheimer’s disease on an individual level. We currently study groups of people to try to understand how those with cognitive problems differ from those who live out their lives with all of their cognitive abilities intact. We haven’t quite reached the point of being able to say with confidence what will happen to any single person, which we will need to do in order to treat individual people as therapies are developed.

“We’re working hard in this field, and we will eventually figure it out, but we’re not quite there yet.”

What failures did you face along the way?

“We always try to learn from our failures and things that didn’t go exactly according to plan.

“Because our study was part of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, we used data that had been collected over many years, rather than creating new data. Because of this design, our failures were observed when results did not appear as we’d anticipated. These ‘failures’ lead us to rethink the questions we were asking and how we were approaching the problem we were trying to solve.”

How have you expanded on this research since your initial finding in 2013?

“We now know that brain function changes long before the onset of cognitive problems. The next question is: What makes some people susceptible to these brain changes?

“I have been working on that question by focusing on physical health. More than half of people over the age of 60 have two or more significant health conditions. Because nothing in the human body works in isolation, cells and tissues in the body are always communicating with one another to allow us to function. Health conditions that affect other parts of our bodies could also have a significant impact on our brains.

“We have found that health conditions such as hypertension and glucose intolerance affect brain function in some of the same areas that are affected in Alzheimer’s disease. We have also found that combinations of health conditions affect brain function.

“The good news is that many of these health conditions are treatable, so with proper diagnosis and treatment, we may be able to stave off some of the health-related effects on brain function.”

Head over to our Accomplishments page for more information on Dr. Beason-Held’s research, and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024