Ebola Virus: Lessons from a Unique Survivor

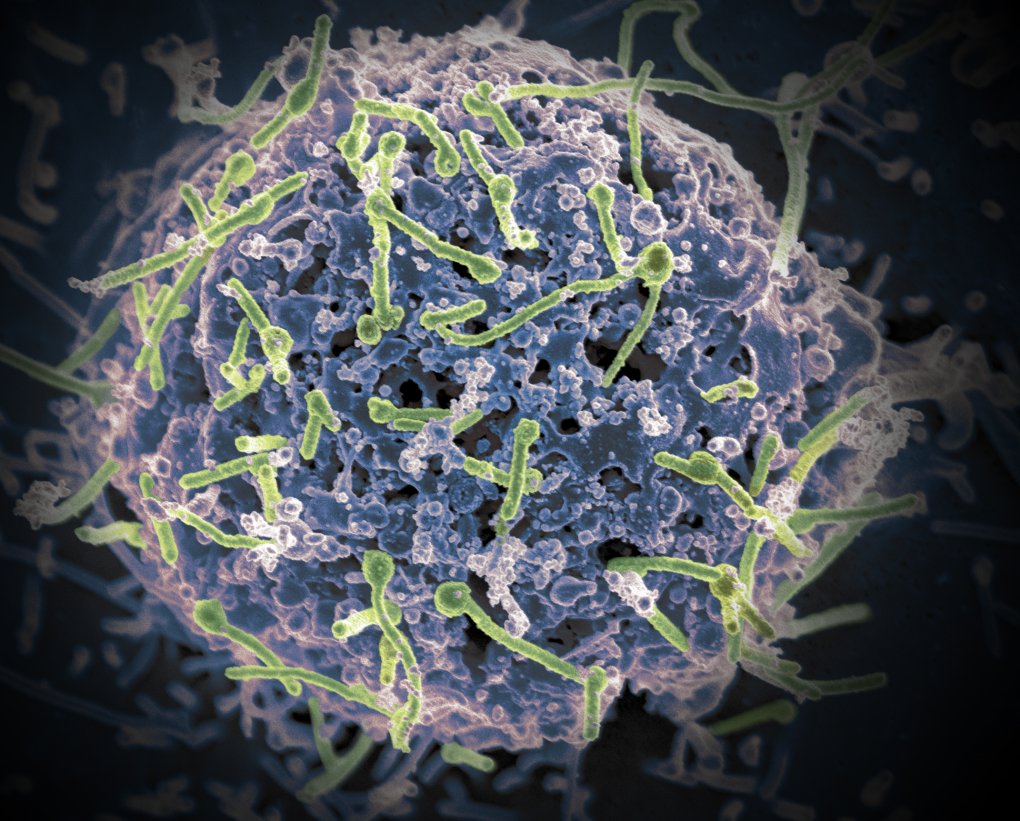

Credit: National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH

Ebola virus (green) is shown on cell surface.

There are new reports of an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. This news comes just two years after international control efforts eventually contained an Ebola outbreak in West Africa, though before control was achieved, more than 11,000 people died—the largest known Ebola outbreak in human history [1]. While considerable progress continues to be made in understanding the infection and preparing for new outbreaks, many questions remain about why some people die from Ebola and others survive.

Now, some answers are beginning to emerge thanks to a new detailed analysis of the immune responses of a unique Ebola survivor, a 34-year-old American health-care worker who was critically ill and cared for at the NIH Special Clinical Studies Unit in 2015 [2]. The NIH-led team used the patient’s blood samples, which were drawn every day, to measure the number of viral particles and monitor how his immune system reacted over the course of his Ebola infection, from early symptoms through multiple organ failures and, ultimately, his recovery.

The researchers identified unexpectedly large shifts in immune responses that preceded observable improvements in the patient’s symptoms. The researchers say that, through further study and close monitoring of such shifts, health care workers may be able to develop more effective ways to care for Ebola patients.

The Ebola virus is a filovirus that can be passed from person to person through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids. Once in the body, Ebola is adept at disarming the immune system and then rapidly destroying the vascular system. Its damage to blood vessels lowers blood pressure, leading to shock, organ failure, and death in two of every five people who contracted the virus during the West African outbreak [3].

That’s the life-threatening situation that the American health-care worker faced when he contracted Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone, West Africa. A week into his illness, he was transported from Sierra Leone to the NIH Clinical Center, where he arrived in serious condition, suffering from fever, intractable diarrhea, and internal bleeding. He received intensive, around-the-clock care, but was not given an experimental Ebola treatment.

Soon after admission, his condition turned critical [4]. Despite receiving optimal care, his kidneys and liver began to fail. His lungs were also severely affected and he had to be placed on a respirator for 10 days. Imaging tests later revealed damage at multiple sites in his brain and spinal cord.

Then, on day 20, he took a dramatic turn for the better. His condition continued to improve gradually and, 33 days after falling ill, doctors released him from the hospital. Seven months later, most of the brain lesions had disappeared. Twelve months post infection, he bounced back to feeling almost “normal.”

In the new study, the team, including John Kash and Jeffery Taubenberger of NIH’s National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, monitored some of the molecular changes taking place as the health-care worker endured this terrible ordeal. The team’s primary window into the infection was the day-to-day changes in gene expression of his white blood cells.

Interestingly, the data showed that the concentration of Ebola virus in the bloodstream peaked just after his arrival in the United States, or before he became critically ill. In fact, about two weeks into his illness, there were no traces of Ebola virus in his white blood cells at all. And yet he remained critically ill for six more days.

Over the course of the illness, his white blood cells showed telling shifts in gene activity. For the first two weeks, gene expression patterns exhibited a spike in genes involved in the innate immune system, the body’s non-selective first line of defense against infection. Those patterns also revealed a rise in cellular responses that indicated DNA damage and cell death, indicating ominously that the virus was winning the battle.

A striking transition in gene activity occurred from day 13 to day 14, as the adaptive immune system (Ebola-specific antibodies and killer T cells) kicked in to target the virus. By day 20, the immune system had completely cleared any signs of free virus in his blood. His gene expression also showed a clear shift from patterns indicative of continued tissue damage toward tissue repair responses.

That’s a pretty remarkable story of survival. And it shows that, contrary to what was once thought, the harm done by the Ebola virus to a victim’s body is much more than just producing rapid dehydration from profuse diarrhea. Thanks to aggressive fluid management at NIH, this patient was never dehydrated, and yet he developed multiple organ failure.

This story is a testament to the value of having the right biomedical research team and infrastructure in place at the right time to take advantage of opportunities to learn more about the virus. In our efforts to prepare and respond to the next Ebola outbreak, like the one now happening in Congo, it will remain vital to continue to learn from our experiences and share those insights.

References:

[1] Ebola Outbreak 2014-2015. World Health Organization

[2] Longitudinal peripheral blood transcriptional analysis of a patient with severe Ebola virus disease. Kash JC, Walters KA, Kindrachuk J, Baxter D, Scherler K, Janosko KB, Adams RD, Herbert AS, James RM, Stonier SW, Memoli MJ, Dye JM, Davey RT Jr, Chertow DS, Taubenberger JK. Sci Transl Med. 2017 Apr 12;9(385).

[3] 2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[4] Severe Meningoencephalitis in a Case of Ebola Virus Disease: A Case Report. Chertow DS, Nath A, Suffredini AF, Danner RL, Reich DS, Bishop RJ, Childs RW, Arai AE, Palmore TN, Lane HC, Fauci AS, Davey RT. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Aug 16;165(4):301-314.

Links:

- Ebola Treatment Research (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

- Laboratory of Infectious Diseases (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/NIH)

- Ebola Virus Disease—Democratic Republic of Congo (World Health Organization)

NIH Support: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, January 31, 2024