From the Annals of NIH History

Visual Sandwiches: Lantern Slides from NCI’s Tissue Culture Section

There’s a lot of hands-on work in a museum, much of it involving dust and some sneezing. But the thrill of holding and preserving something created by someone decades before you were born is what keeps a curator reaching for dust masks. Recently, I went through many such masks cleaning and photographing 199 lantern slides from the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Tissue Culture Section dating from the 1940s through the 1960s. And I loved every minute.

Lantern slides, also known as glass slides, are constructed by binding a positive emulsion of an image on a glass plate. Sometimes the image is matted like a painting and sometimes it is allowed to run to the edge of the glass plate. Then another glass plate is placed on top and the visual sandwich is stuck together by taping around the edges. The images were viewed using a projector. Lantern slides became popular in the late 19th century as photography developed, although “magic slides” with hand-painted images and drawings to entertain or educate date back to the 17th century.

This lantern slide (left) doesn’t look like much even after it has been cleaned—note the touches of dirt in the corners. But when the image, held between the glass plates, is lit, stunning luminescent cells appear (right). The Office of NIH History is still in the process of identifying what this slide depicts.

This particular collection of lantern slides chronicles the contributions of the NCI Tissue Culture Section (TCS), which was begun by Wilton Earle in 1937. Virginia Evans took over as chief upon Earle’s death in 1964, and Katherine Sanford replaced Evans when she retired in 1973. Sanford retired in 1994. The collection of lantern slides eventually made its way to the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum.

The TCS was a powerhouse of cell culture research for over 50 years, making important contributions to the methods of cell culturing and our understanding of how cells become cancerous. For example, TCS scientists established the first cloned cell line; created the first cell culture medium with a known chemical composition; developed techniques to grow cultures on cellophane or glass; devised mass suspension cultures for vaccine development; and invented or improved many of the flasks used in cell culturing, including the T flask.

They also pioneered microphotography techniques that enabled them to make detailed images of cancerous and normal cells in various conditions, and photographically documented their techniques and instrumentation. Those images became the basis for this lantern slide collection.

After nearly 80 years, the lantern slides were a bit grimy and the tape on several had loosened or come off. To clean them, I wore white cotton gloves and a dust mask and used Q-tips dipped in deionized water to scrub them, being careful not to get near the tape so that water wouldn’t inadvertently get between the glass layers. Then I replaced the tape that needed to be replaced with paper artist tape.

The final step was to photograph them. Scanning both sides of the lantern slides and then aligning the digital images on top of each other is the gold standard, but because I was working at home during the pandemic without a gold standard scanner, my innovative husband rigged a small photography studio in the basement so that I could capture rather good images of the slides. After being photographed, the slides were tucked into archival lantern slide envelopes, put in order, and placed into an archival box.

Photo by Michele Lyons

Cleaning lantern slides requires archival paper templates to fold into envelopes for cleaned slides (left), swabs for wiping the slides (center), artist paper tape to reseal the slides (on reel), a non-static brush for a final swipe of cleaned slides (top center), white cotton gloves to keep your body oils off the cleaned slides (right), and deionized water (top). The water does not leave a residue.

Now safe for at least another 80 years, what will become of these lantern slides? Their images will be used in a new display that will be installed this summer in the lobby of Building 6, the original home of NCI and the TCS. The display will also feature a few pieces of TCS glassware from our collection. Selections from this large collection were transferred to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in 1991, the Smithsonian recognizing the TCS’s important contributions to biomedical research.

An online exhibit featuring all of the lantern slides, glassware, and a wealth of information about the TCS and its scientists is in the planning stages. Check the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum’s website at history.nih.gov in the future to see and learn more about these lovely images and the scientific work they represent.

Michele Lyons has been the curator in the Office of NIH History since 1995 and wears many hats while documenting NIH’s work through collecting scientific and clinical instrumentation, images, documents, and oral histories. Before coming to NIH she was at the National Building Museum. In her spare time, she enjoys hiking.

Lantern Slides Images

This lantern slide is labeled “chick heart.” It’s an example of the dozens of beautiful cell culture microphotographs of normal and cancerous cells taken by the NCI Tissue Culture Section over decades of work. The slides are now in the NIH Stetten Museum.

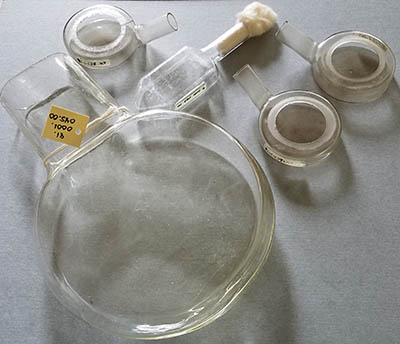

Here’s just a few of the dozens of culture tubes in the NIH Stetten Museum Tissue Culture Section (TCS) collection. The small tube with the conical tip (center top) is called a T-flask and was invented by the TCS. When a T-flask was centrifuged, the cells collected in the conical tip allowing fresh medium to be added without losing cells. T-flasks come in many sizes.

The small round cells with short necks are modified D-flasks. Dr. Alexis Carrel at the Rockefeller Institute developed the D-flask in 1923 to submerge the clots into culture medium, making the cells easier to feed. Dr. Wilton Earle (TCS) improved this method by adjusting pH, oxygen, and CO2 levels. His D-flasks have an open top that also made viewing the cultures under a microscope easier.

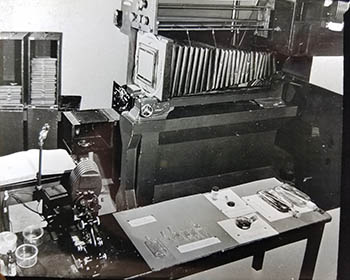

In this lantern slide image, you can see the side and rear of the NCI Tissue Culture Section’s still camera and various culture vessels displayed on the table. The Section modified the D-flask and invented the T-flask and other flasks for growing cell cultures.

This page was last updated on Thursday, March 10, 2022