Alcohol Accelerates Cardiovascular Aging

IRP Research Suggests Older Adults May Benefit From Severely Limiting Alcohol Consumption

A recent IRP study reveals that consuming alcohol worsens the typical decline of the cardiovascular system seen in aging rats.

It seems like every news report touting the health benefits of a daily glass of wine is soon followed by another that claims consuming any amount of alcohol harms health. While the jury is still out on this issue for younger individuals, a recent IRP study suggests that alcohol consumption may accelerate the typical age-related erosion of the cardiovascular system.1

Many scientific studies have established the myriad ways that aging and alcohol independently diminish the capacity of the heart and blood vessels to effectively move blood — and the vital oxygen and nutrients it carries — around the body. However, the effects of those two forces in combination remains an outstanding question with potentially significant implications for health and public policy.

“The elderly population is growing, and they’re also consuming more alcohol, so it’s a very important relationship to study, but there are almost no studies focused on the interactions between alcohol and aging,” says IRP senior investigator Pal Pacher, M.D., Ph.D., the new study’s senior author. “Older adults could also be more vulnerable to problems even at lower levels of alcohol consumption, so alcohol could be disproportionately harmful in elderly populations compared to young people, and most prior studies have focused on young animals, but young people don’t generally have severe cardiovascular problems.”

To fill in that gap, Dr. Pacher’s IRP team put young and older rats — aged 3 months and 2 years, respectively — on two different six-month-long diets containing the same amount of calories, but with one containing no alcohol and the other offering the animals access to a solution containing roughly the same concentration of alcohol as a typical beer. Blood tests confirmed that the rats in the latter group ended up consuming significant amounts of alcohol, although it is difficult to equate their alcohol consumption to human drinking since rats’ bodies process alcohol more quickly than ours do. Even so, Dr. Pacher maintains that the study’s results are relevant not only to people who drink heavily, but also individuals who consume alcohol more moderately.

Dr. Pal Pacher

And the study did indeed produce results aplenty. Many of alcohol’s effects were shared between the younger and older animals, although they were worse in the older group. For instance, cardiac cells died at a faster rate in the alcohol-consuming rats than in those without access to alcohol, and this effect was noticeably larger in the older animals. Dr. Pacher’s team also observed a decrease in the functioning of energy-producing mitochondria in the heart muscle cells of the alcohol-consuming rats — again, one that was larger in the older animals. In addition, these malfunctioning mitochondria produced more reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), which cause extensive damage to DNA and important proteins when they bounce around inside cells.

“Mitochondria are really important in the heart because you need energy for muscle contraction,” Dr. Pacher explains. “The heart has lots of mitochondria, so if you have fewer or less healthy mitochondria, you have less energy for the muscles in the heart to contract in order to pump blood.”

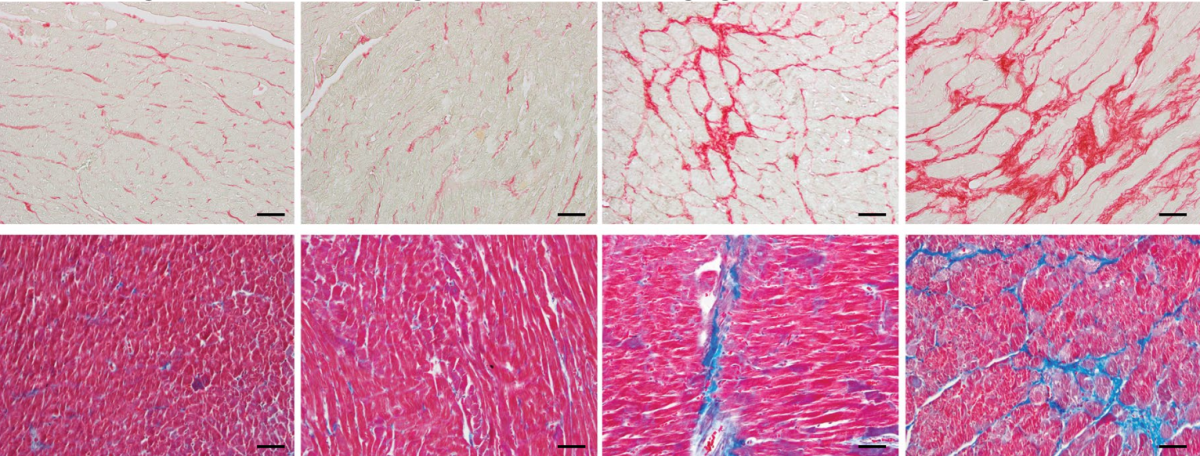

Other ways alcohol affected the older rats were even more concerning. Over the course of the six-month study, none of the younger rats showed signs of fibrosis in their hearts, a process in which inflexible scar tissue replaces cardiac muscle. However, all of the older rats showed signs of cardiac fibrosis, and those that consumed alcohol showed much more of it. That ‘fibrotic’ scar tissue, in turn, impaired the ability of the animals’ hearts to fill with blood because the inflexible fibrotic tissue can’t relax and expand as well as normal heart muscle. Alcohol also decreased the flexibility of blood vessel walls in all the animals, but only the aging rats showed signs of significantly increased ‘total peripheral resistance’ (TPR), reflecting the additional force required to move blood through stiffer vessels. All of these changes would spell major trouble for a human, especially an older one.

“Under normal conditions, cardiovascular coupling ensures that cardiac contractions efficiently transmit blood through the vascular system, but alterations in either the heart or blood vessels can disrupt this coupling,” explains Dr. Pacher. “That’s the case here, and it means the heart has to exert more work to get the same amount of blood through the vascular system. At the same time, both aging and alcohol make the heart’s mitochondria less efficient, so you have less energy when the heart requires more of it to pump the same amount of blood because the blood vessels are stiffening. On top of that, the heart itself is stiffening, so it has a harder time increasing its pumping to compensate for the stiffer blood vessels. This whole phenomenon of cardiovascular de-coupling is a major risk factor for heart attacks and heart failure.”

These images from the study show signs of fibrosis in the rats’ hearts (red in top images, blue in bottom images). There was no detectable fibrosis in the young rats that didn’t consume alcohol (far left) and the young rats that did (second from left). Older rats had noticeable fibrosis even when they didn’t consume alcohol (second from right), and alcohol made it much worse (far right).

All told, the study provides strong evidence that alcohol is “not just a toxic agent but also a catalyst of biological aging,” Dr. Pacher says. It also points to several therapeutic strategies to curb alcohol’s effects on the cardiovascular system, including treatments that boost mitochondrial function and antioxidants that combat the damage caused by ROS. However, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as they say, so it would be cheaper and perhaps more effective to simply change behavior. As such, Dr. Pacher hopes findings like his will prompt doctors to adjust the guidance they give to older patients about alcohol consumption and spur similar changes in public health guidelines.

“These results clearly suggest that older adults should limit alcohol consumption even more strictly,” he says. “Aging also changes how the body processes alcohol, meaning that moderate drinking might have disproportionately harmful effects in elderly populations compared to younger adults. Understanding alcohol’s impact on the aging cardiovascular system has direct implications for public health, clinical care, and policy.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Mukhopadhyay P, Yokus B, Paes-Leme B, Bátkai S, Ungvári Z, Haskó G, Pacher P. Chronic alcohol consumption accelerates cardiovascular aging and decreases cardiovascular reserve capacity. GeroScience. 2025 Mar 20. doi: 10.1007/s11357-025-01613-w.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, June 24, 2025