Double Trouble for Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease

IRP Researchers Identify Two Types of Liver Damage and a Possible Treatment for One

IRP researchers recently revealed that two different biological processes may cause alcohol-related liver damage.

While alcohol is a source of celebration and relaxation for many, it does come with significant drawbacks, especially when people over-consume it. For people who have trouble controlling their alcohol consumption — a condition called alcohol use disorder (AUD) — one of the most dangerous consequences can be damage to the liver, the organ that filters toxins like alcohol out of the blood.

In honor of Alcohol Awareness Month this April, I spoke with IRP senior investigator Bin Gao, M.D., Ph.D., about his quest to understand how AUD damages the liver and other organs by uncovering the molecules and mechanisms involved in that damage. His IRP lab also investigates how alcohol is processed in the body, producing insights that could be used to identify strategies for reducing alcohol consumption or reversing alcohol’s harmful effects.

Alcohol-associated liver disease is the leading cause of liver cancer and liver scarring, known as cirrhosis, which reduces the liver’s ability to filter our blood. Liver ailments caused by alcohol consumption account for almost half of all deaths from diseases of the liver and are rising dramatically. In fact, alcohol-associated liver disease increased by 23 percent in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet even after five decades of study, there are no FDA-approved drugs available to treat alcohol-associated liver disease. The only cure is a liver transplant, but even that does not always work.

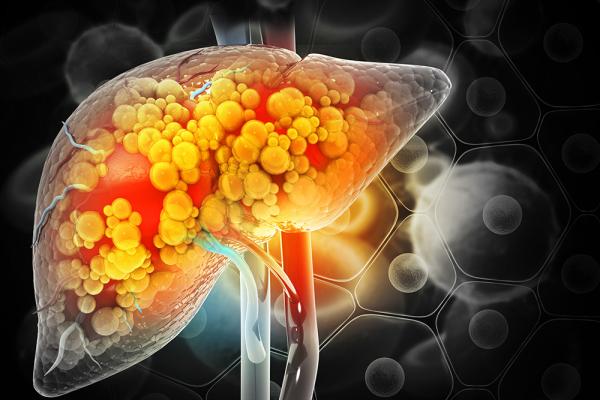

Heavy alcohol use can increase the accumulation of fat in the liver, leading to inflammation, fibrosis, and decreased liver function.

Much of Dr. Gao’s research focuses on understanding the mechanisms that lead to liver inflammation, referred to in medical circles as hepatitis, as well as how that inflammation subsequently damages the organ. In a recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation in 2022,1 Jing Ma, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Gao’s lab, identified two types of severe alcohol-associated hepatitis in both mice and tissue samples from liver transplant patients at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. Although all the patients had similar symptoms, one set of them had high levels of white blood cells called neutrophils in their livers and low levels of cells called CD8+ T cells, while the other group had the opposite balance of these cells in their livers.

“One of the major findings in this study was that the pattern of inflammatory cell infiltration is different from patient to patient,” Dr. Gao says. “This could also suggest they have different mechanisms leading to their liver failure."

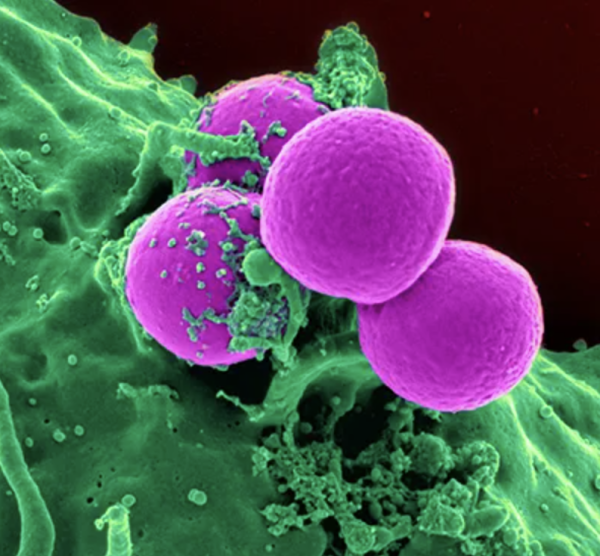

To learn how these differences might influence the most appropriate treatment, Dr. Gao and his colleagues next extracted and sequenced RNA from individual cells in the damaged livers removed from severe alcohol-associated hepatitis patients receiving liver transplants at Johns Hopkins Hospital. The IRP scientists focused in particular on neutrophils in the livers, leading them to identify a group of liver neutrophils that had unique genetic profiles. Specifically, those neutrophils had a gene called CXCL8, which codes for interleukin-8 (IL-8), a chemical that appears to be connected with the processes that lead to liver damage and, eventually, liver failure. The researchers suspect that drugs that block or inhibit the IL-8 made by those neutrophils may prove effective in stopping disease progression.2

A neutrophil (green) engulfing bacteria (purple). Dr. Gao’s research suggests that in some people with alcohol-related liver disease, neutrophils turn against the body instead of defending it.

“I strongly believe that the neutrophil IL-8 target will work, maybe not in all patients, but at least in certain groups of patients,” Dr. Gao says. “I believe this is one of our most important findings, so we’re trying to work with physicians to start clinical trials.”

Dr. Gao is particularly excited about the ‘single-cell sequencing’ technique they used for that study because he believes it can be applied to other organs as well. This is important because the liver isn’t the only organ that AUD harms.

“I think people could use the same approach to study alcohol-associated pancreatitis because there is also a lot of neutrophil infiltration into the tissue in that disease,” he says.

In addition to identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying alcohol-associated liver damage, Dr. Gao is also very interested in understanding how our organs are affected by the way the body processes alcohol. While the liver is the primary tool used to process alcohol, it turns out that other organs are involved as well. Dr. Gao’s team learned this when they created a type of mouse in which the liver lacks aldehyde dehydrogenase-2, an important enzyme that the liver uses to expel the products of alcohol processing from the body. The IRP researchers expected to see evidence of alcohol processing and removal of the resulting toxic molecules from the body drop precipitously after drinking alcohol in those mice, but the drop was much smaller than anticipated.

Dr. Bin Gao

“If you read the scientific literature or textbooks, you’ll learn that the liver is responsible for processing about 98 percent of alcohol,” Dr. Gao says, “but when we treated those mice that lack alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in the liver, alcohol processing only dropped by about 30 percent. I thought this doesn’t make sense. It should be a huge drop.”

This surprising finding led Dr. Gao’s team to begin studying other organs to see how they contribute to alcohol processing in the body. The scientists found that in mice that lacked the gene for aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 in liver cells, other organs like the intestines and fat tissues pick up the slack for the hindered liver.

By revealing the intricacies of how various parts of the body interact with the alcohol we drink, research like Dr. Gao’s will move scientists closer to finding effective treatments for patients whose health is harmed by their alcohol consumption.

“Alcohol use disorder is a huge public health issue,” Dr. Gao says, “but I think we can find some ways to treat it and save patients’ lives.”

References:

[1] Ma J, Guillot A, Yang Z, Mackowiak B, Hwang S, Park O, Peiffer BJ, Ahmadi AR, Melo L, Kusumanchi P, Huda N, Saxena R, He Y, Guan Y, Feng D, Sancho-Bru P, Zang M, Cameron AM, Bataller R, T acke F, Sun Z, Liangpunsakul S, Gao B. Distinct histopathological phenotypes of severe alcoholic hepatitis suggest different mechanisms driving liver injury and failure. J Clin Invest. 2022; 132(14):e157780. doi: 10.1172/JCI157780.

[2] Guan Y, Peiffer B, Feng D, Parra MA, Wang Y, Fu Y, Shah VH, Cameron AM, Sun Z, Gao Bin. IL-8+ neutrophils drive inexorable inflammation in severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. J Clini Invest. In preparation. J Clin Invest. 2024 Mar 19:e178616. doi: 10.1172/JCI178616.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 17, 2024