Moms’ Microbes May Influence Babies’ Future Health

IRP Mouse Study Suggests Intervention Might Reduce Health Problems Associated with C-Section Births

By exposing newborns to the microbes living in their mothers’ vaginas, a new practice called ‘vaginal seeding’ may improve the health of babies born via C-section, according to a new study done in mice.

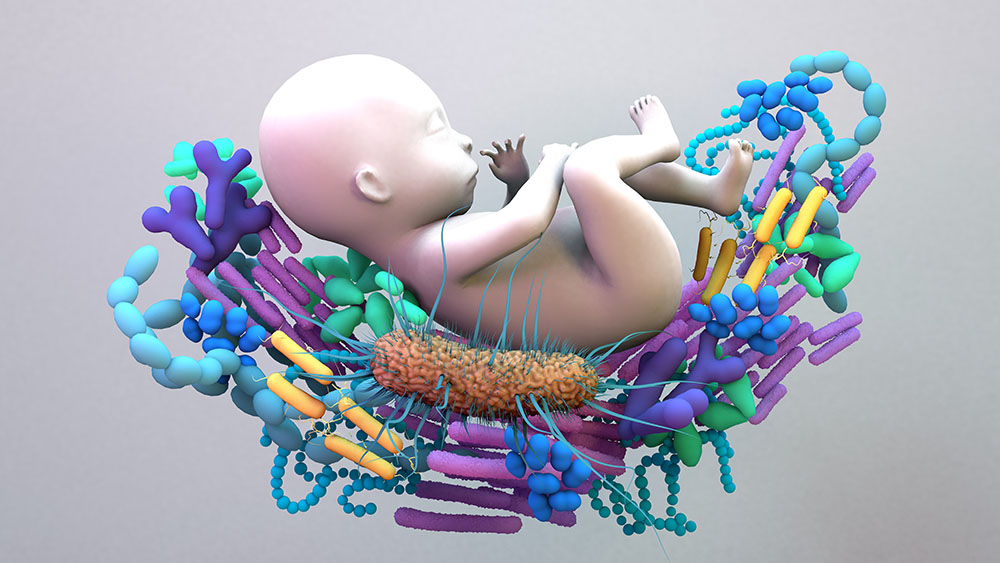

Every kid’s first gift from their mom is half of her DNA, but nearly a third of children born nowadays miss out on a bonus present. That’s because babies born via vaginal delivery are exposed to the microorganisms that live in the vagina, but infants born via Cesarian section are not. A new IRP mouse study suggests that an intervention designed to make up for this missed opportunity could reduce the risk of certain health problems that are more common in babies born via C-section.1

All sorts of ‘probiotic’ products, from pills to yogurts, claim to improve the health of the microbes living in our digestive systems, known as the gut microbiome. Less attention has been paid to other parts of our bodies that bacteria and other microscopic critters inhabit, like the vagina. Nevertheless, a mom’s vaginal microbiome plays a huge role in her child’s future health.

“Our microbiome mostly develops over the first few years of life and is stable into adulthood, so those first few years of life are really critical to establishing a healthy microbiome,” explains IRP Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Suchitra Hourigan, M.D., the new study’s senior author. “During a vaginal delivery, a baby acquires its first microbiome from the mom’s vagina, but birth via C-section bypasses that exposure, and the baby actually gets colonized by the mom’s skin microbes and the microbes that we find in the hospital environment. Since the microbiome differs at the start, it goes on to develop differently through those first few years of life.”

In recent years, scientists like Dr. Hourigan have begun to suspect that initial difference is part of the reason babies born via C-section have a greater risk later in life for health conditions ranging from obesity and type 2 diabetes to asthma and allergies.

“Their microbiome influences how their immune system develops,” Dr. Hourigan says. “Babies born by vaginal delivery tend to have a more protective microbiome and different immune development that is protective against these diseases.”

The microbiome someone has at the start of life has a large influence on his or her microbiome and health as a child and adult.

Luckily for the many babies born via C-section, Dr. Hourigan and other researchers have found that a practice called ‘vaginal seeding’ can make the skin and gut microbiomes of an infant born via C-section more similar to those of a baby delivered vaginally. The procedure involves wiping a newborn’s skin, nose, and mouth with a swab that has been exposed to their mom’s vaginal microbes. However, it has not yet been proven that vaginal seeding has any effect on future health, which is why Dr. Hourigan’s IRP team is currently running a clinical trial comparing the health of children born via C-section and exposed to vaginal seeding to those born in the same manner who did not receive vaginal seeding.

Unfortunately, since vaginal seeding is done at the very beginning of a person’s life, it will take time for that study to yield any conclusive results. Hence the new study Dr. Hourigan led, which used samples of feces from the babies in her clinical trial to transfer those babies' gut microbes into the digestive systems of mice without microbiomes of their own — a process known as a 'fecal transplant.'

“Our primary interest is to see if vaginal seeding in our clinical trial decreases the risk of obesity in children, but to get to that point, we need many more children in our study and we need to follow them for years, so we wanted to be able to assess whether we could see any hints of that outcome using a mouse model,” Dr. Hourigan says.

Right off the bat, the IRP researchers discovered that mice that received fecal transplants from babies exposed to vaginal seeding had different and more diverse microbiomes a few weeks after the transplant. More intriguingly, male mice that received fecal transplants from babies exposed to vaginal seeding ended up having less abdominal fat than male mice that got their transplants from babies not exposed to vaginal seeding. Since increased abdominal fat is linked to an increased risk of the sorts of ‘metabolic’ health problems that stem from obesity, like type 2 diabetes and heart disease, this finding suggests that vaginal seeding might turn out to protect babies born via C-section from such conditions. Importantly, this possibility is not diminished by the fact that only male mice in the study showed any differences based on the source of their fecal transplant, since such sex differences are commonly seen in mice that begin life without microbiomes of their own.

Dr. Suchitra Hourigan

Along with reduced abdominal fat, male mice that received fecal transplants from babies exposed to vaginal seeding had lower blood levels of a hormone called GLP-1, which is known to be involved in appetite and digestion. Their feces also contained different amounts of certain substances, known as metabolites, created by the body and the microbes that inhabit it, and those levels of metabolites were statistically associated with amounts of abdominal fat in the mice that received feces from babies not exposed to vaginal seeding. Such hormonal and metabolic differences provide clues as to exactly how the animals’ microbiomes were influencing their levels of abdominal fat.

“Looking at these metabolites gives us a better idea of the microbiome’s function, rather than just looking at the actual microbes themselves,” Dr. Hourigan explains. “What’s interesting is that in other mouse and some human studies, these metabolites have correlated with obesity independently, so we were pleased to see that they were correlated with abdominal fat in our study.”

The results of the IRP study represent an encouraging sneak-peak of some of the findings Dr. Suchitra’s clinical trial may eventually yield, as well as show her some indicators to look at down the line. For instance, the study suggests her team should be sure to examine levels of abdominal fat in the children participating in the clinical trial rather than only measuring their height and weight. Ultimately, if that study and others show a lower risk of health problems for babies born via C-section and exposed to vaginal seeding, the practice could one day become a standard part of medical care for newborns.

“This is really the first study showing that the changes we make in infants via vaginal microbiome seeding may have a positive effect on metabolic health,” Dr. Hourigan says. “It’s really promising to see this early on in our clinical trial and gives us more reason to continue it to see if the same effect is seen in babies.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Namasivayam S, Tilves C, Ding H, Wu S, Domingue JC, Ruiz-Bedoya C, Shah A, Bohrnsen E, Schwarz B, Bacorn M, Chen Q, Levy S, Dominguez Bello MG, Jain SK, Sears CL, Mueller NT, Hourigan SK. Fecal transplant from vaginally seeded infants decreases intraabdominal adiposity in mice. Gut Microbes. 2024 Jan-Dec;16(1):2353394. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2353394.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, October 15, 2024