IRP’s Marston Linehan Receives HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service

Honor Recognizes Groundbreaking Advances in Cancer Genetics

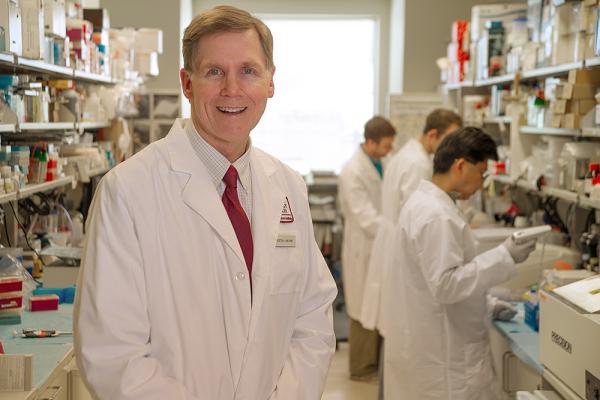

Dr. Marston Linehan received the HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service in April 2024 in recognition of his discoveries about the genes that drive kidney cancer.

As an undergraduate majoring in English, IRP senior investigator W. Marston Linehan, M.D., was fascinated by the complex poetry of 18th-century writer William Blake. But as much as he loved puzzling out the deeper meanings behind literary metaphors and imagery, Dr. Linehan eventually realized he wanted to do work that had more tangible benefits for people. Biology, with its own deep and complex mysteries, fit the bill.

Nearly 40 years later, Dr. Linehan’s pioneering work in the study of genetic forms of kidney cancer has transformed how doctors treat the disease. Over that period, he and his colleagues discovered or co-discovered nine distinct forms of kidney cancer and identified 10 different genes that cause them. These discoveries have provided the basis for targeted therapies and new approaches to treatment and, this year, earned Dr. Linehan the HHS Secretary’s Award for Distinguished Service, the highest honor given by the US government’s Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

When Dr. Linehan first came to NIH in 1982, his charge was to set up a program to treat patients with cancers of the genitals and urinary tract, including kidney cancer. At the time, all cases of kidney cancer were regarded as the same disease and there was no effective therapy for patients in its advanced stages. Even today, after the development of some effective therapies, 400,000 people develop kidney cancer annually across the world and more than 100,000 die as a result. Death rates were even more discouraging when Dr. Linehan first stepped foot into the NIH Clinical Center, since the only hope back then was to catch the disease early and remove the tumors surgically.

“We treated those cancers all the same — surgically — and we gave all patients the same drugs, none of which really worked,” Dr. Linehan recalls. “We’ve come to understand over the years that kidney cancer is not one disease. It’s a number of different types of cancer that happen to appear in the kidney.”

But before they came to that realization, Dr. Linehan and his colleague, former IRP senior investigator Berton Zbar, M.D., set out to identify what they thought would be a single gene that drives all cases of kidney cancer. They identified an abnormal stretch of DNA in patients with kidney cancer, which they thought might be the location where the errant, cancer-causing gene resides, and began efforts to map that section. That turned out to be an even bigger challenge than expected.

President Barack Obama visited Dr. Marston Linehan’s lab in 2009 to learn about his pioneering research. Also with him were then-NIH Director Francis Collins (left) and former HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius.

“This was 18 years before the human genome was sequenced and there was no genetic map to work from,” Dr. Linehan says. “We had to make our own. After two years of our labs working together, we calculated that it if we all worked 10 hours a day, 6 days a week, it would take us 54 years to find the gene in that location, so we shifted gears.”

Dr. Linehan and Dr. Zbar had been focusing their research on ‘sporadic, non-familial’ kidney cancers, the kind that aren’t passed down from parent to child. However, cancer geneticist Alfred Knudson had recently described a ‘tumor suppressor’ gene that blocks tumor growth, and people who inherited two damaged copies of this gene had a greater risk of developing cancer. Drs. Linehan and Zbar thought the kidney cancer gene they were looking for might be the same sort of gene. By focusing on families in which multiple members developed kidney cancers, the scientists could trace the inheritance of the responsible mutation without having to map the actual genome, just as one might trace the inheritance of a gene for, say, red hair or blue eyes.

To work with those families, Dr. Linehan established a research program at the NIH Clinical Center to evaluate and treat patients with the familial form of kidney cancer associated with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL). Patients with VHL are at risk for the development of tumors in multiple organs, including the kidneys, pancreas, spine, adrenal gland, inner ear, brain, and the eye’s retina. Dr. Linehan recruited colleagues from across the entire Intramural Research Program to work on this project, ultimately involving 29 different laboratories from 9 different NIH Institutes and Centers. He partnered with investigators in a number of fields, including surgery, ophthalmology, endocrinology, and radiology.

Over the next eight years, the IRP team analyzed DNA from a large number of individuals with VHL. Because the majority of these patients and their non-affected family members had been carefully studied at the Clinical Center to determine who was affected and who was not, in the spring of 1993, the team was able to find the cause of VHL, a mutation in a tumor suppressor gene they named VHL — one of the earliest cancer genes identified. The next year, Dr. Linehan and his colleagues showed that the VHL gene was also the primary cause for another form of kidney cancer: the common form of non-hereditary, sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

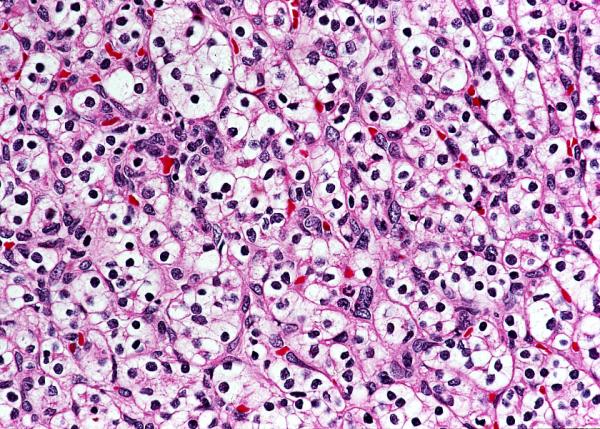

This image from Dr. Linehan’s lab shows cells affected by the form of kidney cancer known as clear cell renal cell carcinoma.

The next step was to figure out how this newly discovered gene actually functioned, or in the case of cancer, malfunctioned, to provide the foundation for the development of a therapeutic approach for the hereditary as well as sporadic form of clear cell kidney cancer. Again, putting into action a group effort, Dr. Linehan and his collaborators identified important partner molecules that worked with the VHL protein. This led to a watershed moment.

“The work suggested this VHL protein complex targets oxygen-sensitive proteins for degradation or destruction,” Dr. Linehan explains, ultimately leading to the identification of hypoxia inducible factor 2 (HIF2) as a potential target for kidney cancer therapy.

Based on those results, scientists at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center developed a drug in 2015 that targeted HIF2. Dr. Linehan subsequently teamed up with IRP senior investigator Ramaprasad Srinivasan, M.D., Ph.D., to begin a clinical trial using the drug.

“We were just blown away by the responses we saw,” Dr. Linehan says. “A huge percentage — nearly 98 percent — of patients with kidney tumors had a significant response or at least stabilized disease in response to the drug. We saw similar improvements in pancreatic, spine, brain, and retinal tumors.”

Jean, a patient with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome, discusses the progress of her treatment with research nurse Geri Hawks and Dr. Linehan.

The drug, belzutifan, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of VHL patients with tumors in the kidneys, pancreas, or central nervous system in August of 2021, nearly 40 years after Dr. Linehan began studying kidney cancer. In December of 2023, the FDA approved Belzutifan for patients with advanced, sporadic, non-familial clear cell renal cell carcinoma — the cancer that Dr. Linehan’s team had previously linked to the VHL gene.

“We've only been giving this drug to VHL patients for the last four of five years, but we've seen a dramatic drop-off in the number of surgeries that these patients need after treatment,” Dr. Linehan says.

Today, thanks to Dr. Linehan’s work, we know there are many different kinds of kidney cancer caused by various different genetic mutations. To date, researchers have identified 19 kidney cancer genes and at least 16 types of kidney cancer that run in families. More importantly, there are a growing number of treatment options for those who have these cancers.

“It has really been the joy of a lifetime to have the opportunity to work with these wonderful, brave patients who have been our partners in this work and to see the responses to treatments that we have observed over the years,” Dr. Linehan says of his decades at NIH. “We have come a long way; however, we still have a long way to go.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, July 1, 2024