Data Mining for Dementia Clues

IRP Research Examines Under-Appreciated Factors in Alzheimer’s Disease

IRP scientists led by Dr. Keenan Walker are investigating how inflammation and other relatively unexplored factors contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

This June, the observance of Alzheimer’s and Brain Awareness month reminds us just how devastating the impact of Alzheimer’s and other dementias is across the world. About 55 million people are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias such as frontotemporal dementia and Lewy body dementia. This includes the estimated 6.7 million people in the U.S. over age 65 with Alzheimer’s disease, a population whose cognitive decline imposes huge financial costs on the American economy and often unrecognized burdens on the unpaid family members who provide care for those patients.

While the disease has been a target of intensive investigation ever since Alois Alzheimer first discovered clumps of amyloid beta protein and tangles of tau in the brain of a deceased patient in 1906, scientists have made only modest progress in treating it. Efforts to design drugs targeting the abnormal globs of amyloid and tau thought to cause Alzheimer’s have met with only limited success. That’s why IRP investigator Keenan Walker, Ph.D., is taking a different approach: exploring the link between dementia risk and the immune system.

“My lab focuses on immunity and inflammation as something that is clearly relevant to many forms of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Walker says. “While we know there’s a link, we still have a lot of open questions about exactly how and when features of immune function become risk or protective factors. We want to identify specific immune or inflammatory proteins or pathways that might contribute directly to development of dementia.”

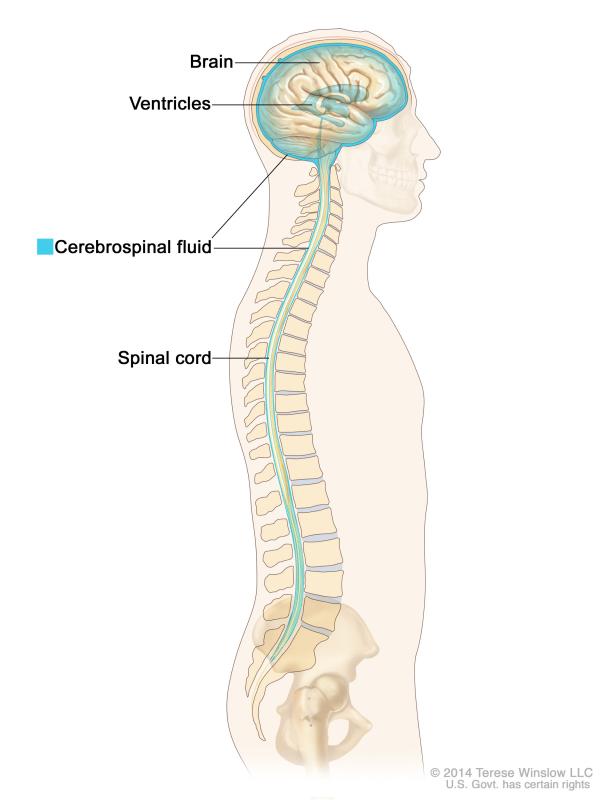

The cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord tends to contain more inflammatory proteins in people with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia.

Studies have shown that people with signs of Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment tend to have higher levels of inflammatory proteins in their blood and cerebral spinal fluid. Dr. Walker’s team is building on these findings by analyzing data from a large, long-term study of aging, which collected measurements for different indicators of inflammation found in the blood as well as tested participants’ cognitive abilities at several timepoints years apart.

“We are taking an untargeted and data-driven approach where we measure literally thousands of proteins in the blood and go one by one to find which are predictive of future dementia risk,” Dr. Walker says. “In doing that, we learn about what aspects of biology, at the molecular level, might be different in individuals who are at risk for dementia or other changes to brain structure or function.”

Dr. Walker’s team ultimately identified 38 proteins whose levels in the blood predicted a higher Alzheimer’s risk in the next five years, and then narrowed them down to 16 that appeared to predict risk 20 years in advance. The researchers then performed genetic analyses to look for an overlap between genetic variants that lead to abnormal levels of these proteins and genes known to affect the risk of developing Alzheimer’s. One protein, SVEP1, stood out as a likely causal contributor to Alzheimer’s disease.1

Now that his team has identified SVEP1, Dr. Walker says the next step is to see if manipulating its production in animal models can slow progression of Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. He notes that, historically, inflammatory proteins were thought to be a byproduct of Alzheimer’s disease, building up in the brain in response to the death of neurons. However, his research is instead hinting that inflammation may precede a decline in brain health rather than follow it.

Dr. Keenan Walker

“It’s starting to become more apparent that the inflammation or immune dysfunction may be a mechanistic feature of dementia,” Dr. Walker says. “Although I don’t necessarily believe that immune dysfunction triggers the pathology underlying dementia, I do think it may accelerate it. Immune function may be an important determinant of whether individuals with, for example, Alzheimer’s pathology in their brain actually become symptomatic and develop significant cognitive decline.”

Of course, improving care for patients with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia is difficult not only because of the mysterious biological factors behind those ailments, but also because of differences in the way they are diagnosed and managed in different populations. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s may be as much as double in African American patients compared with white individuals, so Dr. Walker and his research team are paying close attention to this dynamic as well. For example, they recently performed an analysis of data collected through the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Cohort to try to uncover differences between people from different racial and ethnic groups included in that massive dataset, one of the world’s oldest and largest.

Addressing racial disparities in the way dementia is diagnosed will be key to improving care for the disease, as people of color are significantly more likely to develop the condition but may be less likely to be referred to studies or receive a diagnosis.

After sifting through the data, Dr. Walker’s team encountered something surprising: Alzheimer’s diagnoses were actually more common in white individuals than people of color in that study’s population. However, other results were more in line with past studies, such as the finding that African American patients appeared to have worse symptoms at the time of diagnosis. Reasons for these differences aren’t clear, Dr. Walker says, but since most of the study’s participants enroll only after seeking help from their doctors for memory problems, it’s possible that African American patients might be less likely to be referred to research studies when complaining of cognitive difficulties, or they may need to have more severe symptoms than white individuals to get an official diagnosis. In any case, what is clear is that scientists’ explorations of Alzheimer’s must include attempts to understand and address the racial disparities that harm particular groups of patients and their families.2

“Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are extremely debilitating from a public health perspective, so there’s clearly a deep need,” Dr. Walker says. Despite the challenges he and other Alzheimer’s researchers routinely encounter, he remains optimistic. “There's always something new. People are really advancing the field very quickly, and even in my short career, there's been so much progress.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Walker KA, Chen J, Zhang J, Fornage M, Yang Yunju, Zhou L, Grams ME, Tin A, Daya N, Hoogeveen RC, Wu A, Sullivan KJ, Ganz P, Zeger SL, Gudmundsson EF, Emilsson V, Launer LJ, Jennings LL, Gudnason V, Chatterjee N, Gottesman RF, Mosely TH, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne CM, Coresh J. Large-scale plasma proteomic analysis identifies proteins and pathways associated with dementia risk. Nat Aging 2021 May 14; 1:473–489.

[2] Lennon JC, Aita SL, Bene VAD, Rhoads T, Resch ZJ, Eloi JM, Walker KA. Black and White individuals differ in dementia prevalence, risk factors, and symptomatic presentation. Alzheimers Dement. 2022 Aug; 18(8):1461-1471. doi: 10.1002/alz.12509.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Friday, June 16, 2023