Digging Up the Roots of Food Allergies

IRP Research Aims to Explain the Perils of Peanuts and Other Foods

IRP scientists led by Dr. Pamela A. Guerrerio are investigating why some people have life-threatening reactions to certain foods.

If you are a parent of school-age children, you’ve probably received a list of prohibited lunch foods and bans on birthday cupcakes. Going out to eat or cooking for guests can present a similar minefield of ingredients that many people must avoid. If it seems like food allergies are on the rise, it’s not your imagination. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that the prevalence of food allergies has increased by 50 percent since the 1990s, making it a serious public health concern.

This May, Food Allergy Awareness Week reminds parents, kids, teachers, food service workers — really all of us — that we must remain vigilant to the risks of reactions to certain foods. These allergies affect nearly 32 million Americans, including 1 in 13 kids. If you think about the average classroom, that could be two or three children with severe allergies in one room. For many, even a tiny amount of an allergen can trigger a serious, even life-threatening response by the body’s immune system. To address this growing concern, IRP senior investigator Pamela A. Guerrerio, M.D., Ph.D., and her colleagues in the Food Allergy Research Section at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) are working to unravel how genetics, immune system development, and environmental factors interact to cause food allergies in children.

“It’s becoming clearer that the development of food allergies likely involves both a genetic predisposition as well as exposure to triggers in the environment,” Dr. Guerrerio says. “Use of antibiotics early in life that disrupt the microbiome, vitamin D deficiency, and the age that solid foods are introduced into the diet might all contribute to the risk of developing food allergies.”

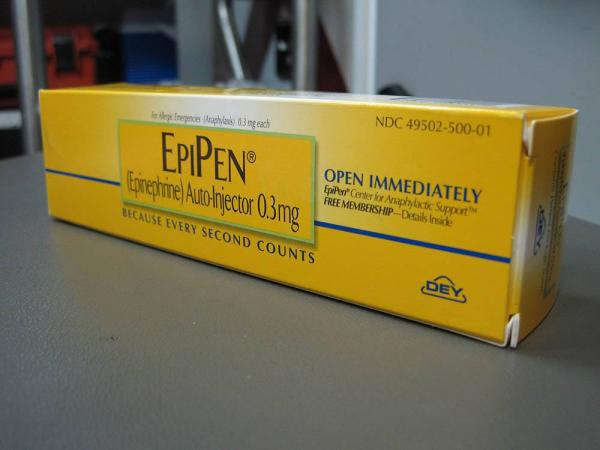

People with severe food allergies must constantly carry syringes filled with fast-acting epinephrine in case they accidentally encounter the food they are allergic to. Image credit: Intropin via Wikimedia Commons

Most food allergies develop in childhood, and while some kids are lucky and outgrow them, they may not go away with age. Dairy, eggs, wheat, nuts, soy, sesame, and fish or shellfish are common culprits, although more than 170 different foods have been found to cause reactions in some people. While mild allergies can be treated with medications called antihistamines, more severe reactions require injection of a fast-acting medicine called epinephrine — the ‘epi’ in the ‘EpiPens’ that many severe allergy sufferers carry at all times — followed by a visit to the emergency department. Avoiding foods that cause allergic reactions is the cornerstone of management, which can curtail kids’ ability to eat a nutritious diet.

“Since most of the major food allergens are nutritionally dense, there is a concern that children who need to avoid these foods because of their allergy will be at risk for a number of nutrient deficiencies,” Dr. Guerrerio says. “We want to define these risks and what measures can be implemented to ensure optimal growth and overall health.”

Since there are so many potential factors contributing to the development of allergies, Dr. Guerrerio and her colleagues are studying disorders caused by single-gene mutations that appear strongly associated with allergy development. For example, they have been studying a condition called Loeys-Dietz yndrome, which is caused by a mutation in the gene that codes for a receptor for TGF-beta, a protein involved in growth and development. Even though this condition primarily affects connective tissues, patients have a noticeably higher risk of developing food and other allergies, as well as a condition called eosinophilic esophagitis, in which immune cells accumulate in the esophagus and can cause food to get stuck. The TGF-beta protein has long been known to play an important role in how the immune system develops, so Dr. Guerrerio and her team have been conducting experiments to see how disrupting its function can lead to allergies.1

Dr. Pamela Guerrerio

“It’s pretty amazing — because there are so many factors that we think play a role in the development of food allergy — that just disrupting this one gene, this one pathway, is enough to cause food allergy,” Dr. Guerrerio says. “I think this tells us that TGF-beta could be a really important pathway in terms of understanding the disease and that targeting this pathway could have therapeutic benefit.”

Acute allergy attacks are not the only risk that stems from food allergies; the diet and lifestyle limitations needed to prevent reactions can negatively affect kids as well. Dr. Guerrerio’s lab has been conducting studies to gauge the impact of food allergies on children’s nutrition and subsequent development and health. For example, her IRP team recently published a study showing that kids with multiple food allergies were more likely to have low bone density than kids with fewer or no food allergies, a relationship that grew more pronounced as the kids got older.2 This discovery suggests that more dietary restrictions and a longer period of life spent avoiding nutrient-dense foods due to allergies may have harmful consequences for bone health. Dr. Guerrerio’s team has also identified relationships between food allergies and lower quality of life, especially among older children and teens, so her group is currently looking at factors that might help people with food allergies to decrease their fear of allergic attacks and make it easier for them to participate in social activities.

“One of the most important factors we found was actually age,” Dr. Guerrerio says. “The older the patient, the more likely there was a negative impact on their quality of life. We’re not sure if this is because teenagers are assuming more responsibility for managing their allergies, but I think it’s also just more limiting as kids get older because they can’t have the usual social interactions like going out to eat with friends and ordering whatever they want.”

Food allergies pose social problems as well as health problems, complicating tasks like dining out at a restaurant that many people navigate with ease.

Dr. Guerrerio hopes her research will help lead to new prevention strategies and treatments that target the genetic and immune processes that govern food allergies. Her research also may have applications for alleviating seasonal allergies and other conditions linked to over-active immune responses, such as eczema and asthma. At the same time, she says, her team’s continuing research into how coping with food allergies can affect children’s mental health, as well as their growth and development, will guide clinical management and improve the care of these patients.

“Food allergy has become a growing public health problem around the world,” Dr. Guerrerio says. “However, we are making strides in understanding both the environmental, genetic, and immune factors that drive food allergy development, and I am very optimistic that in the not-too-distant future we will have more effective prevention and treatment options to offer families.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Laky K, Kinard JL, Li JM, Moore IN, Lack J, Fischer ER, Kabat J, Latanich R, Zachos NC, Limkar AR, Weissler KA, Thompson RW, Wynn TA, Dietz HC, Guerrerio AL, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA. Epithelial-intrinsic defects in TGFβR signaling drive local allergic inflammation manifesting as eosinophilic esophagitis. Sci Immunol. 2023 Jan 6; 8(79):eabp9940. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abp9940.

[2] Nichols-Vinueza DX, Mateia A, Hatzimemos A, Michael M, Rasooly M, Dempsey C, Magnani A, Brittain E, Boyce AM, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA. Determinants of bone density in children with immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2023 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/all.15696.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Friday, June 16, 2023