Predicting Risks and Benefits for Lung Cancer Screening

IRP Researchers Refine Tools to Maximize the Benefit from Life-Saving Tests

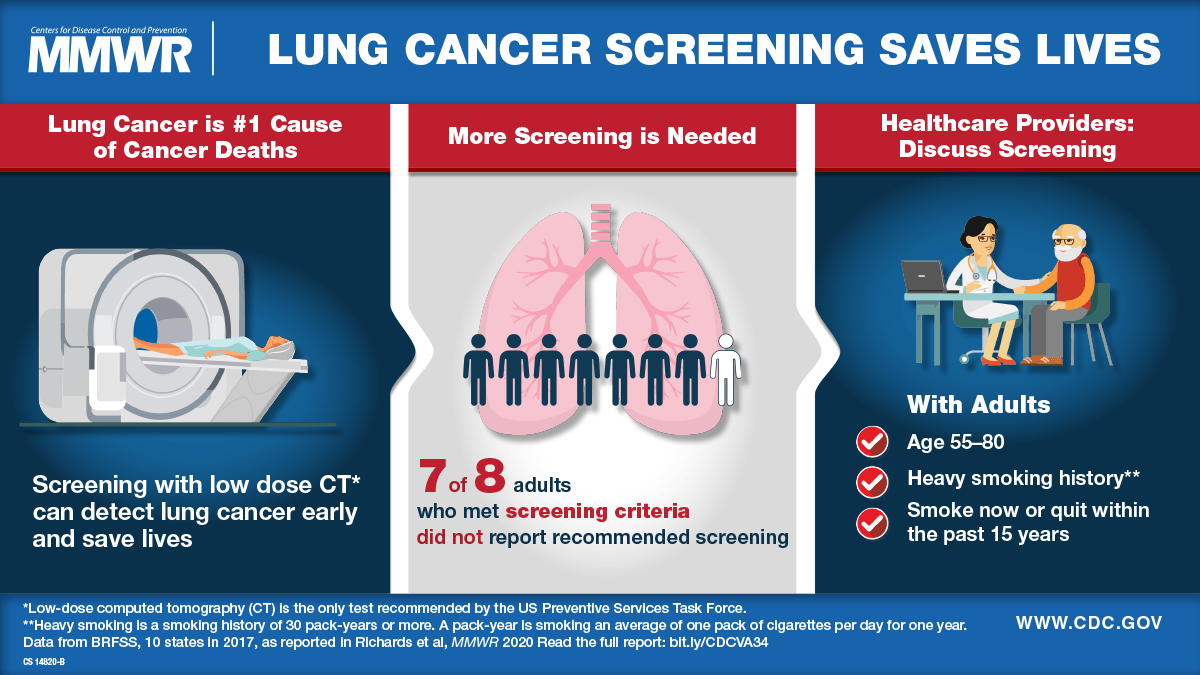

Data analysis by a pair of IRP researchers has pointed to better ways to figure out which people would receive the most benefit from lung cancer screenings using computed tomography (CT) scanners like this one.

Eleven years ago, IRP senior investigator Hormuzd Katki, Ph.D., had a bit of an eureka moment during a press event announcing the results of the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial, which demonstrated that annual screenings cut the risks of dying from lung cancer in heavy smokers by 20 percent.

“It struck me as I read the trial results that not only was this a very important trial, but that it was possible that different people will have different benefits from lung cancer screening,” Dr. Katki remembers. “Even within this group of very high-risk smokers who were part of the trial, you can identify some people who get much more benefit than other people, and that has implications for who should be offered this kind of screening.”

As we observe National Lung Cancer Awareness Month this November, estimates predict more than 236,000 new cases of lung cancer will develop in the U.S. by the end of 2022 and 130,000 people will die from the disease. With a five-year survival rate under 25 percent, preventing it or catching it early is key to survival. To do that, regular screenings are necessary, but the risks of the computed tomography (CT) scans used to do them — including radiation exposure and potential erroneous false positive results — need to be balanced with the benefits. That’s where researchers like Dr. Katki and his long-time collaborator, IRP senior investigator Anil Chaturvedi, Ph.D., come in.

Based on the results of the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force — the advisory body that develops health screening guidelines for the U.S. population — released recommendations in 2013 for annual CT screening tests for heavy smokers between ages 55 and 80 who continued to smoke or had quit within the past 15 years. After the trial’s results came out, Dr. Katki reached out to Dr. Chaturvedi, and together they mapped out a plan to use the data from the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial to identify the characteristics of those who benefitted most from annual CT scans.

“Anil and I knew there were some people in the group who didn’t get a lot of benefit from the screening and that there would be other people who may not fit the recommended criteria for annual screenings but who would also benefit highly from screenings,” Dr. Katki says.

This poster from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showcases the latest recommendations for lung cancer screening.

Ultimately, they combined data from the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial with another large-scale trial, as well as data from a U.S. health survey of the entire population, to develop and validate risk models that identified which current and former smokers would be the best candidates for annual screenings. They determined that age, smoking history, and race were key factors for predicting risk for lung cancer.1

“Using this model, it is possible we could screen fewer individuals or the same number of individuals but prevent more lung cancer deaths by using a risk prediction approach,” Dr. Chaturvedi says.

However, the two scientists realized that using risk prediction alone would weight screening recommendations toward those whose expected remaining years of life might be too few to obtain long-term benefits from screening. Such people tend to be older and have a higher risk of developing lung cancer, and they are also at higher risk for other causes of death. Therefore, they may benefit less from screening than younger, healthier people who likely have more years of life to gain through early detection of lung cancer.

Dr. Anil Chaturvedi

“That was a paradigm shift in our thinking where we went from using a risk prediction model to a benefit prediction model,” Dr. Chaturvedi says. “Instead of estimating an individual’s risk of lung cancer or lung cancer death, our team estimated an individuals’ life years to be gained from screening2 if she or he were to be diagnosed with lung cancer early, assuming the treatments would be effective.”

Due to the risks and expense involved in CT scans, it would be problematic if doctors over-used them to screen people who wouldn’t benefit much from them. The more personalized lung cancer risk assessments proposed by Dr. Chaturvedi and Dr. Katki would allow physicians to advise patients more carefully and to know which patients they should strongly encourage to undergo the scans.

More recently, Dr. Katki has been collaborating with colleagues in the IRP, across the U.S., and around the world to find ways to further refine their risk and benefit models for lung cancer screening. For instance, he and IRP colleagues Li Cheung, Ph.D., Rebecca Landy, Ph.D., and Lingxiao Wang, Ph.D., are collaborating with scientists from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) to collect and integrate data that includes more members of under-represented minorities in order to develop improved prediction models that could reduce health inequalities in screening. In addition, Dr. Katki and collaborators are working with a company in the United Kingdom to develop artificial intelligence tools to predict whether a nodule found on the lungs is cancerous or is likely to become cancerous within the next year. They have proposed an approach to update risk assessments with the imaging results over time.

Dr. Hormuzd Katki

“We found that the AI score was highly predictive of whether you would get cancer in one year,” says Dr. Katki. “This suggests a future where you could have an AI score that will tell you not only your chance of having cancer now, but your chance of having cancer in the future. That helps you set up an interval for screening.”

Despite all these advances in the science of screening, getting people to actually undergo regular screenings still remains a challenge. Even under the current guidelines, participation in lung cancer screening has been disappointingly low.

“When I talk to physicians, I get the sense that our healthcare system is not very well set up for preventive screenings,” Dr. Katki says. “We don’t set up a visit just to talk about screenings; it’s added on at the end of an appointment for something else. You’re supposed to have a shared decision-making session, but few clinicians really know what that entails. There are no standards for it.”

Likewise, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force hasn’t integrated risk and benefit predictive models into their screening guidelines. As of now, there are still impediments to implementation due to the need for physicians to take the extra time to capture additional information about their patients and put it to use in determining who would benefit most from screening.

“I suspect that the Task Force wants to see professional societies begin recommending prediction tools and see how they work in routine practice and show that it is practical,” Dr. Katki says. “They want to see that some health systems are using prediction tools to achieve important goals, such as improved uptake of screening among high-benefit people and reducing racial and ethnic disparities. That’s what we hope our work will do."

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Katki HA, Kovalchik SA, Berg CD, Cheung LC, Chaturvedi AK. Development and validation of risk models to select ever-smokers for CT lung cancer screening. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2300-2311. doi: 10.1001/jama.20166255.

[2] Cheung LC, Berg CD, Castle PE, Katki HA, Chaturvedi AK. Life-Gained-Based Versus Risk-Based Selection of Smokers for Lung Cancer Screening. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(9):623-632. doi: 10.7326/M19-1263.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023