Psychological Stress Damages Brain’s Blood Vessels

Mouse Study Illuminates Potential Mechanism Behind Mood and Anxiety Disorders

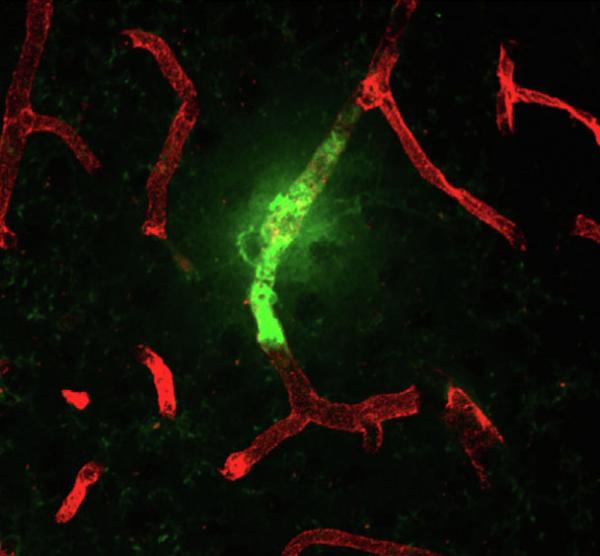

New IRP research shows that psychological stress not only triggers depression-like behavioral changes in mice but also causes tiny ruptures in their brains’ blood vessels.

Millions of Americans suffered from depression and anxiety even before COVID-19 began upending their lives. To make matters worse, the stresses of living through a pandemic might not only worsen mental health but could also wreak havoc on the brain itself. New IRP research has found that psychological stress damages blood vessels in the brains of mice and dramatically alters the behavior of genes in certain blood vessel cells.1

Scientists have long used animal models to investigate human illnesses from cancer to Parkinson’s disease. However, using them to study psychological phenomena like mood and anxiety disorders presents particular challenges, as a mouse cannot tell scientists what it is feeling. Nevertheless, researchers have made valuable discoveries by observing changes in animals’ behavior that resemble those seen in human mental illness.

Researchers in the lab of IRP senior investigator Miles Herkenham, Ph.D., have spent years studying mice exposed to an experimental technique called chronic social defeat, in which an aggressive mouse is permitted to ‘bully’ another mouse for a few minutes each day. Just like the stress of repeated encounters with a demanding boss or teasing classmates can contribute to feelings of sadness and anxiety in humans, multiple exposures to social defeat can cause marked behavioral changes in mice that are similar to those seen in patients with depression and anxiety disorders, including a loss of interest in social interaction and a decreased willingness to leave safe spaces to explore their surroundings.

“Social defeat is a very natural thing for social animals, which both mice and humans are,” says Dr. Herkenham, the new study’s senior author. “By looking at mice undergoing this kind of stress, we can gain insight into what a human might be going through.”

Dr. Miles Herkenham

Of course, like humans, not all animals that experience psychological stress show changes in behavior. According to past studies in Dr. Herkenham’s lab, in mice that do behave differently following chronic social defeat, immune cells in the brain called microglia show changes in gene activity similar to those that occur when microglia are exposed to substances found in blood. This prompted Dr. Herkenham and Dr. Michael Lehmann, Ph.D., the new study’s first author and a staff scientist in Dr. Herkenham’s lab, to consider the possibility that chronic social defeat was causing tiny ruptures in the brain’s blood vessels, called microbleeds, in these ‘susceptible’ mice.

The pair’s new study confirmed their hypothesis, showing that mice that displayed behavioral changes following chronic social defeat also showed signs of microbleeds randomly distributed throughout their brains. What’s more, in those susceptible mice, the cells that line blood vessels and keep blood out of the brain, known as endothelial cells, showed significantly altered activity in more than 3,000 genes, depending on how many consecutive days a mouse was exposed to chronic social defeat.

The IRP researchers subsequently sifted through a large database of past research to identify biological processes that might be affected by the 578 genes with particularly large increases in activity after chronic social defeat. One day of social defeat stress boosted genes related to inflammation in the animals’ endothelial cells, whereas repeated exposure to social defeat elevated the activity of genes related to processes that spur healing, including the production of cellular growth factors and the sprouting of new blood vessels. Meanwhile, a week of recovery from social defeat stress revved up genes that bring white blood cells to a damaged area to aid healing.

This image from the new IRP study shows a blood vessel leak (green) in the brain of a mouse that experienced chronic social defeat.

“The changes in gene activity suggest there’s a mess that needs to be cleaned up in the brain’s blood vessels,” says Dr. Lehmann. “They’re damaged and cells need to divide in order to replace the area that has been affected, and at the same time other cells come in to clean up the mess. That’s the typical pattern seen in wound healing and that’s the pattern that was saw in the endothelial cells. All of this was triggered by psychological stress.”

Intriguingly, the genes that were more active in the brain endothelial cells of the stressed mice were similar to those that previous research has shown to be active in the blood vessels of mice with genetic or drug-induced high blood pressure, as well as in mice with mutations that weaken the barrier between the brain and its blood vessels. This bolsters the theory that physical changes in the brain’s blood vessels could cause depression or anxiety disorders in some individuals.

To confirm that the new study’s findings apply to humans, researchers will need to examine the brains of individuals with mood or anxiety disorders after they have died to see if the endothelial cells in their brains’ blood vessels show similar changes in gene activity to those of mice exposed to chronic social defeat. Drs. Herkenham and Lehmann also plan to investigate whether certain interventions, such as medications that lower blood pressure, exercise, or a more cognitively stimulating environment, can prevent psychological stress from triggering behavioral changes in mice or psychological ailments in humans.

“Once you know the mechanisms behind a disease, coming up with a therapy becomes much easier,” says Dr. Lehmann. “This study, along with our past research, suggests that damage to blood vessels may be a key factor — though not the only factor — that could lead to the behavioral changes we see in depression.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Analysis of Cerebrovascular Dysfunction Caused by Chronic Social Defeat in Mice. Lehmann ML, Poffenberger CN, Elkahloun AG, Herkenham M. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 May 12;S0889-1591(20)30028-3. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.030.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024