What's New In the NIH Archives

The waning weeks of 2018 were busy ones in the Office of NIH History. We're constantly receiving and cataloguing new donations of historic equipment, images, publications, and more. It’s time to see what our donors have given us lately!

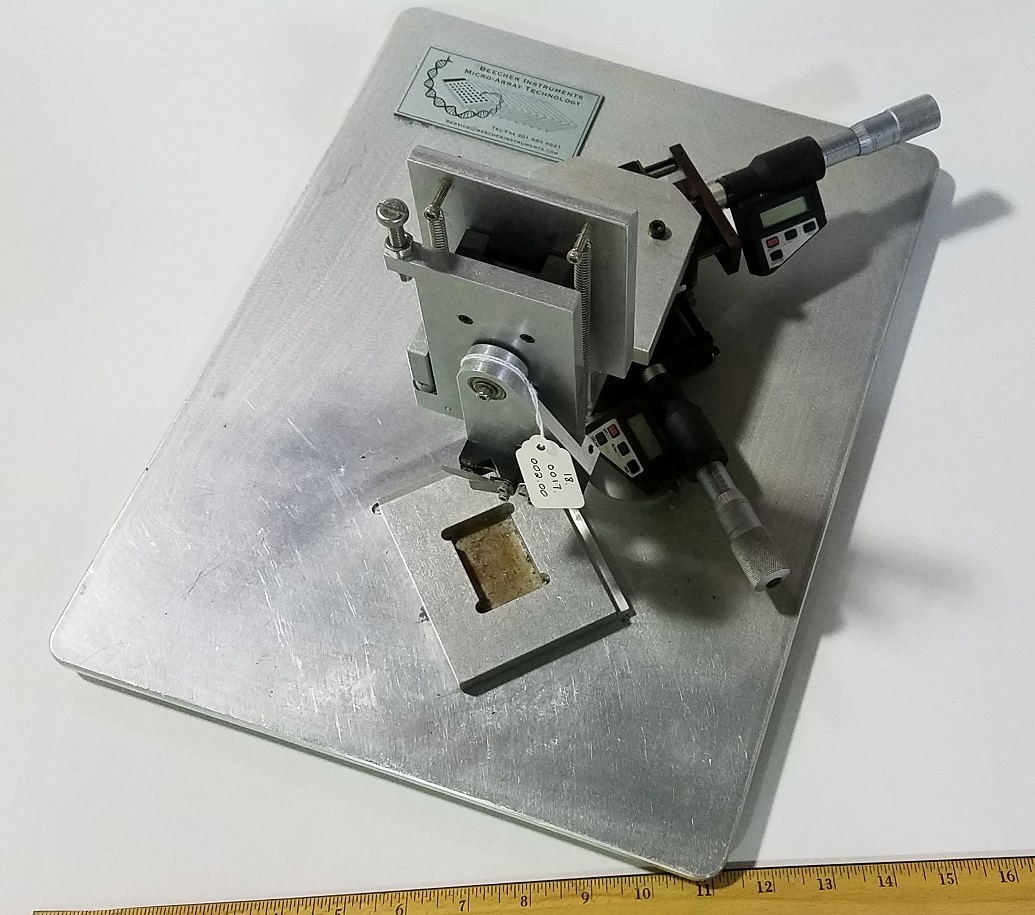

"I thought why could you not invert the concept? Instead of laying down hundreds or thousands of probes, how about laying down hundreds or thousands of tissue spots and probing them one antibody or gene probe at a time," remembers Dr. Juha Kononen of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) about his idea that led to this prototype manual microarray. Tissue array technology performs rapid molecular profiling of hundreds of normal and pathological tissue specimens or cultured cells. Dr. Kononen worked with Drs. Olli Kallioniemi and Stephen B. Leighton to design this tissue microarray which was initially used in the Cancer Genomics Branch. Now, the National Cancer Institute's Tissue Array Research Program (TARP) develops and distributes multi-tumor tissue microarray slides to cancer researchers based on this technology. The quote comes from a 2002 article published in The Scientist.

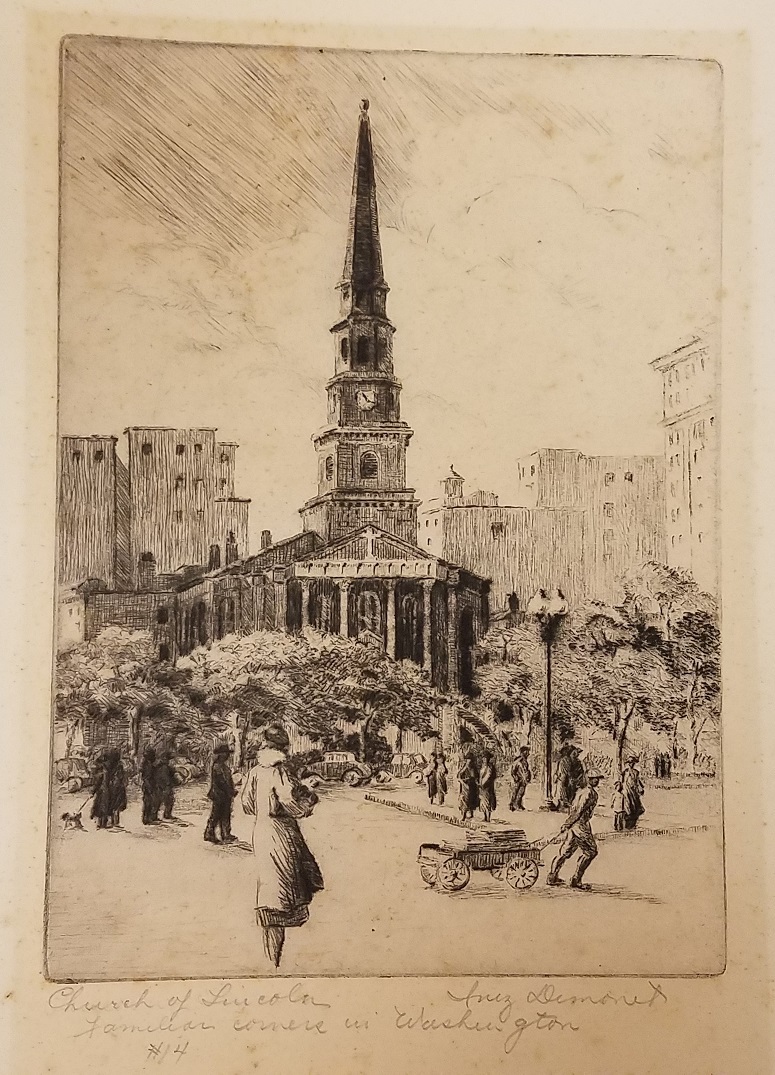

Pedestrians outnumbered the cars at the corner of New York Avenue and H Street NW in the 1930s. Inez Demonet (1897-1980) drew this scene of Washington, D.C.’s New York Avenue Presbyterian Church during her time off from her job as the medical illustrator for the National Institute of Health (singular back then). She was the sole staff artist when she began in 1926, but by 1938 she had become the chief of an entire section: Medical Arts. Known as “Miss D”, she drew illustrations, designed exhibits, and decorated NIH offices until she retired in 1965. Her artworks are in the collections of the Smithsonian and the Corcoran galleries — and now ours.

Where do I go to eat? How can I get a parking permit? Can I hire a contractor I know? And just when can I take a day off? These questions and more were answered in the “NIH & You” booklet for new employees in 2000. Current topics in the online NIH handbook that were not necessary then: how to get a badge, teleworking, and automated systems such as personnel folders.

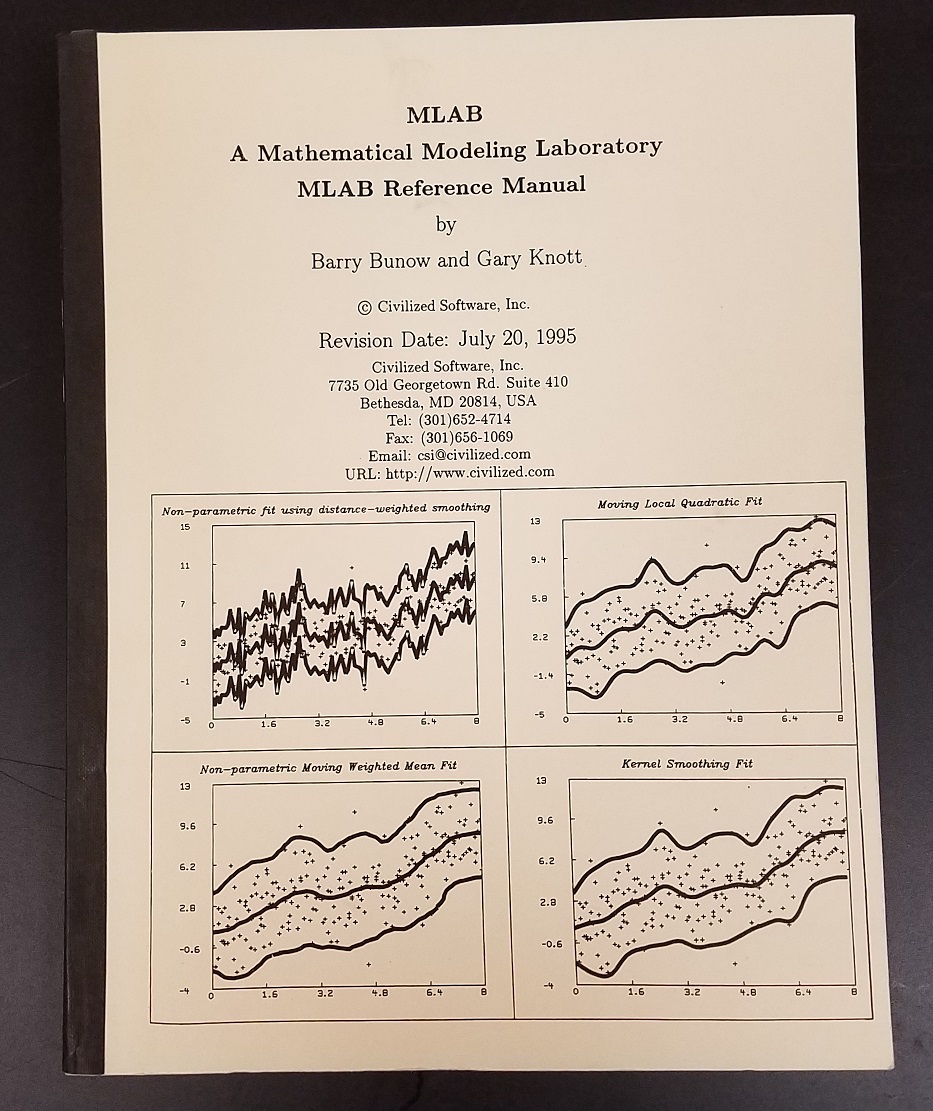

In 1972, a new computer program called MLAB (Modelling Laboratory) revolutionized how researchers used computers. MLAB enabled scientists to formulate equations and evaluate mathematical models using their experimental data, without having to program the computer or wait for results. MLAB was developed by Gary Knott and Doug Reece of the NIH Division of Computer and Research Technology (now the Center for Information Technology). In 1985, Gary Knott and Barry Bunow formed Civilized Software Inc. (CSI). As this 1995 version attests, MLAB is still used — revised, of course.

Dr. Hank Fales, to whom this manual belonged, was the chief of the Laboratory of Chemistry at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and was known for his work on mass spectrometry and for pushing for the computerization of scientific equipment.

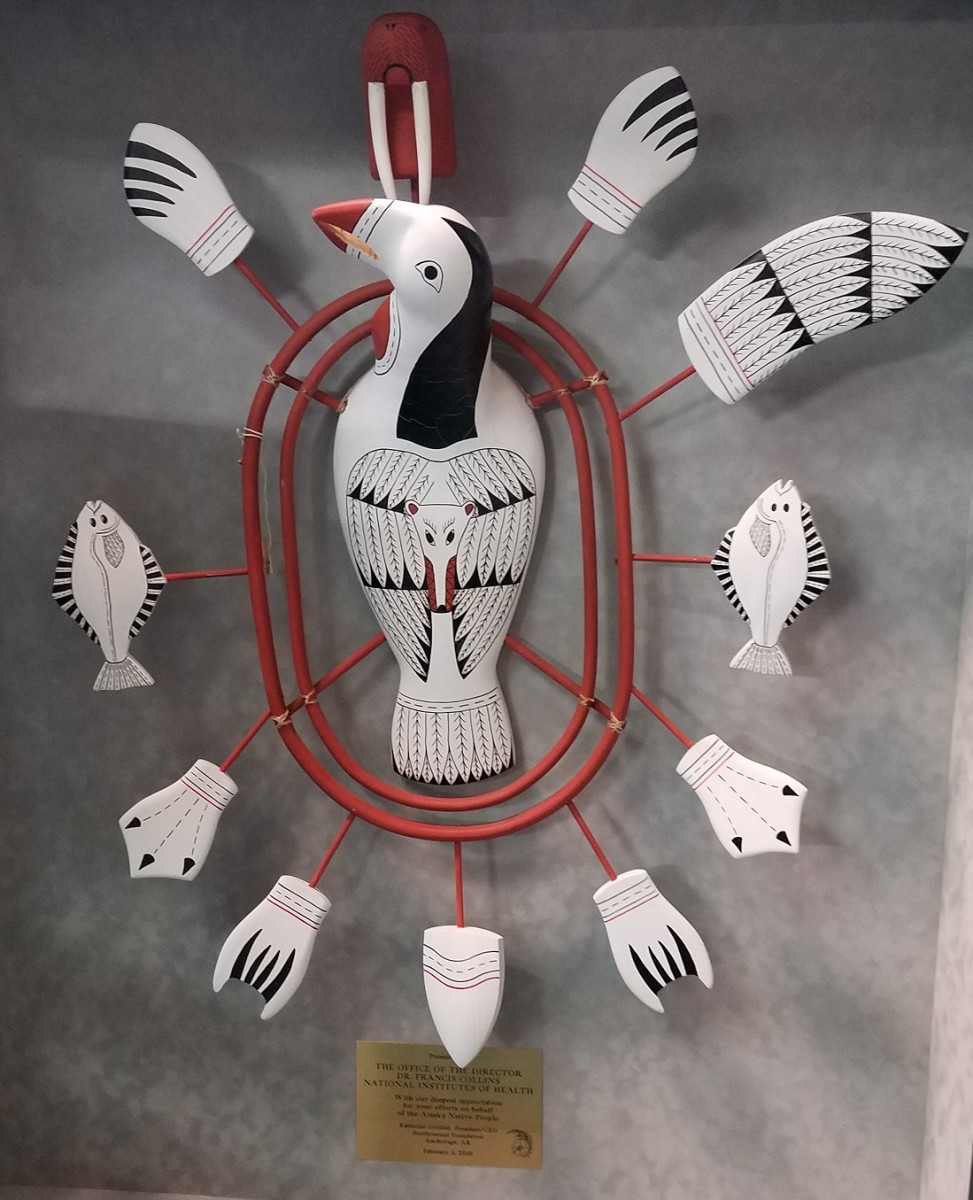

This beautiful loon mask created by Bryon L. Amos includes paws, wings, fish, flippers, and clawed feet. Amos is a Cup'ig Eskimo who grew up in Mekoryuk village on Nunivak Island. He says, "The wood masks express the foremost iconic design of birds [and] sea life mammals with wood rings presenting the earth and the universe in which mankind lives." In 2010, this mask was presented to NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins by the Southcentral Foundation, an Alaska Native Healthcare organization founded by law in 1984 that administers nearly half of the primary care service for Alaska Natives. The NIH works closely with the organization, particularly on family health and genetics.

The quote is from a September 2018 blog post titled "Native American Pavilion Spotlight -- Cool Ice Marketing, Bryon L. Amos," from the Las Vegas Souvenir and Resort Gift Show blog.

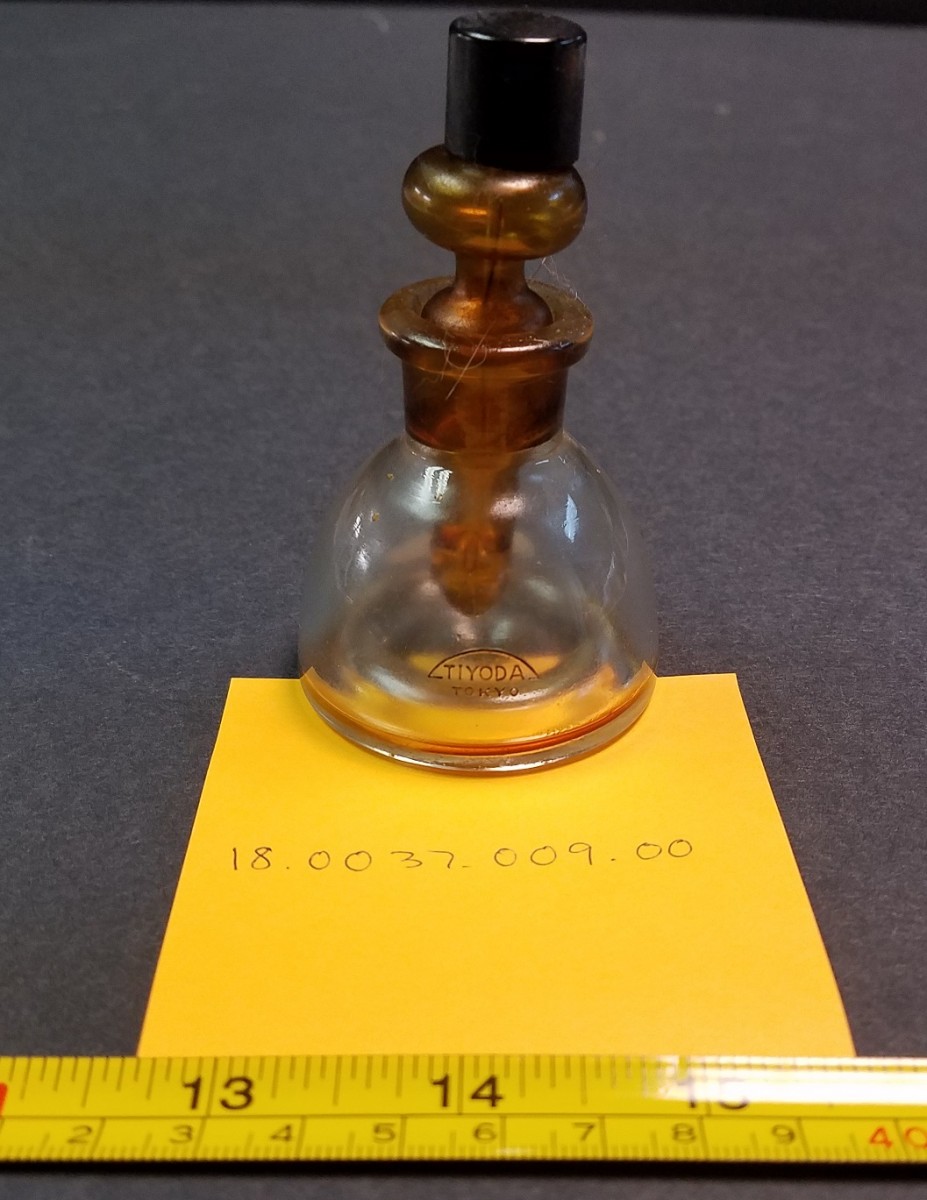

Who knows how old this cute little bottle is? There’s two parts to this microscope accessory — an outer container that holds solvent and an inner reservoir of amber glass for oil. The inner container seals the outer one so that solvent cannot evaporate, and the cap over the dropper is a little tin cup. While this bottle has a Tiyoda (Tokyo) logo, it’s likely that the Japanese company distributed the bottles found in U.S. scientific catalogs from the 1940s-1960s under their mark. This little bottle was used in the Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID).

Aren’t you glad they don’t give flu shots with these? These glass syringes with a patented Luer Lok design were introduced by Becton, Dickinson and Co. in 1925. The plungers and barrels have the same number because they were made to fit precisely together. The Luer Lok held needles firmly but allowed them to be easily removed for cleaning. The NIAID Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases donated them to our collection.

World War I spurred the United States to manufacture its own medical and chemical instrumentation. One of the replacements for a German product was patented by Frank L. Hinkly in Pittsburgh in June 1919. The American Medical Museum Jar was still touted in the 1940s because they were pressed in iron molds and so were “superior to the German jars blown in wooden molds, in that the inside and outside surfaces of the sides are parallel, and thus the view of the specimen is not distorted: the edges and corners of the jars are thick and strong, rather than thin as in the case of the German jar.” They also had a unique system for hanging specimens.

The quote is from the Eimer and Amend and Fisher Catalog, 1942, p. 603.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023