Remembering IRP Scientists Who Gave Their Lives for Their Work

Scientific research is not all writing grants, giving presentations, and publishing papers. There are real risks to probing the secrets of biology, and sometimes scientists lose their lives during the course of their work. In honor of Veterans Day, we woud like to commemorate IRP staff who made the ultimate sacrifice in pursuit of knowledge that can help us prevent and treat diseases that impact so many lives.

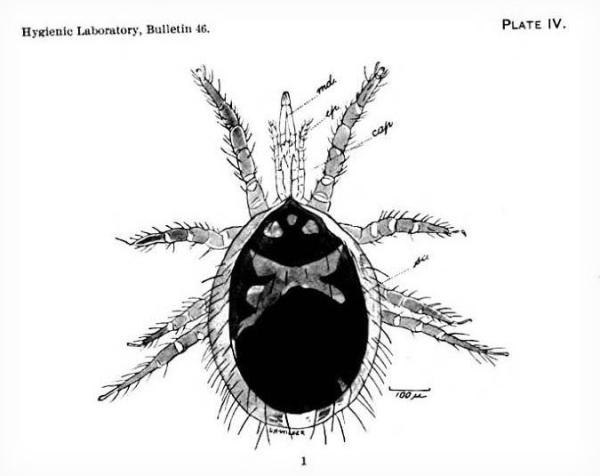

This lovely mite illustrated Dr. William W. Miller’s last publication before he died of typhoid fever on November 24, 1908. Miller got ill while working at the Hygienic Laboratory, the precursor of NIH, fighting the fever for eight weeks. His colleagues wrote that he was modest with “an exceptionally winning and lovable disposition” and “his untimely death terminated a career which had already given promise of a brilliant future.” William Miller left behind a wife and infant daughter. We have no photograph of him.

Miller was born at Water Valley, Mississippi, on June 26, 1880, but moved to Memphis, Tennessee as a child. He attended private schools and then went to University of Virginia where he won the Miller Scholarship for excellence in biology, receiving his MD in 1901. In the next few years, he took a special course at Harvard in pathology, taught at Columbia University, and worked as a pathologist at Roosevelt Hospital. He returned to Memphis in 1905 to enter private practice but a year later joined the Public Health Service and was assigned to Ellis Island. In August 1907, he was sent to the Hygienic Laboratory in Washington, D.C. and participated in the investigation of the origin and prevalence of typhoid fever in the city. According to the memorial statement prefacing his last publication, “during the last summer [Miller] made over a thousand bacteriological examinations in the search for bacillus carriers.” The mite, drawn by Leonard H. Wilder, was the host of a pathogen in rats that Miller described in the June 1908 Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin No. 46.

“But to some men the call of duty echoes a note of real and dreadful danger…. It was such a call as this that came some months ago to Dr. Thomas B. McClintic…when he was delegated to go to Montana to fight an epidemic of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. A short time before he had been married, and the call to fight a disease recognized as communicable and generally fatal must have come as an unwelcome call. He would have been scarcely human had it been otherwise. But he did not falter. Tuesday Dr. McClintic died in the hospital at Washington of the disease he had gone to Montana to fight…. But out in Montana the dreaded fever has been practically eradicated as a result of this one doctor's work. Unquestionably, hundreds of lives have been saved and something worthwhile has been added to the modern science of preventive medicine. And so it is that back in Washington the bride [Theresa Drexel] of an interrupted and now forever ended honeymoon must seek, as have other women sought in the past, what consolation she may from the fact that her husband was called by duty as other men are not called, and that he answered the call as brave men must.” — The Joplin (Missouri) Globe, August 15, 1912

McClintic was born in 1872, in Virginia, and received his MD from UVA in 1896, becoming a Public Health Service officer in 1899. During his career, McClintic served in New York, Mexico, Alaska, and the Philippines. He was on duty in San Francisco during the 1906 earthquake. In 1911-1912, McClintic went back and forth between the Hygienic Laboratory in Washington, D.C. (now NIH) and Montana for his work eradicating Rocky Mountain spotted fever from the Bitter Root Valley. When taken ill himself, he was brought back to Washington, D.C., but died the day of his arrival.

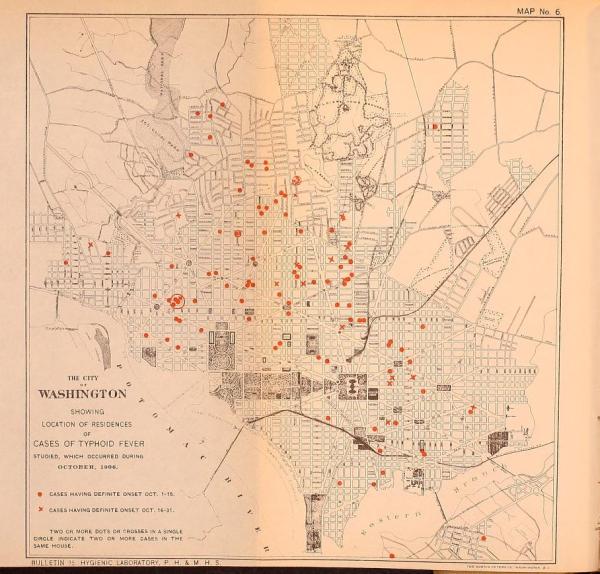

Many of the NIH staff that have died in the line of duty have been technicians. One of these was William Lindgren, who served as a bacteriological technician in the Division of Pathology and Bacteriology at the Hygienic Laboratory (now NIH). As a lab tech, Lindgren performed different kinds of tests; for example, during the 1906 typhoid epidemic in Washington, D.C., Lindgren counted the bacteria found in milk and discovered that the milk was so polluted that it wouldn’t pass Boston’s health codes. This of course spurred Washington, D.C. to enact its own codes regulating milk production. In 1917, Lindgren came down with typhoid fever, although he recovered at Providence Hospital. He did not recover from tuberculosis that he acquired in the laboratory, however, and he died in 1928. Unfortunately, we do not know any more about William Lindgren’s life except that he was a member of the Hope Lodge, No. 20, of Masons. The illustration is a map of the 1906 typhoid fever epidemic based on Lindgren’s work.

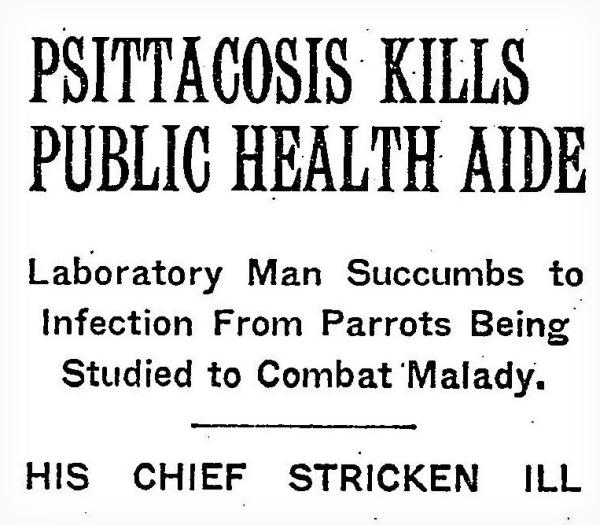

Lab tech Henry “Shorty” Anderson slumped in his chair, holding his head. A horrible headache and high fever announced that despite his best efforts to keep the disease contained, he had caught psittacosis. His boss, Dr. Charles Armstrong, took Anderson to the Navy hospital next door on the 25th and E Street NW campus where NIH was then located. Every day for nearly two weeks, Armstrong visited Shorty in the hospital, promising that he would make sure that Shorty’s bills would be paid on time. Shorty would die on February 8, 1930; on that day, Armstrong was admitted to the hospital with psittacosis, although he would recover. Several other NIH staff members would also get ill. NIH director George McCoy shut down research on the disease, carried by parrots being given as Christmas presents, allowing only himself to clear the two basement rooms where Anderson and Armstrong had worked before having the entire building fumigated. Henry Anderson was memorialized for the Congressional Record by Representative Anthony Griffin (NY) on February 11, 1930: “Yesterday there was interred in Arlington Cemetery the mortal remains of one who may be truly said to have given up his life for the benefit of humanity. He made the supreme sacrifice, not in the midst of stimulating alarums of war but in the silent laboratory — with no hope of praise or reward other than the consoling consciousness of toiling for his fellow men. Who was this man with the heart of the soldier and the soul of the martyr? His name is Harry Anderson. He was a soldier, too, for he served in the World War, from which he came unscathed only to meet his end as a humble laboratory assistant in the United States Public Health Service.”

On Christmas night in 1935, when other families relaxed after a joyful day, the mother and three sisters of Anna Pabst said their goodbyes to her as she succumbed to meningitis. Only four days before, Pabst had been Christmas shopping when she started to feel ill. While inoculating a rabbit in her NIH laboratory with meningitis, the rabbit had moved and some of the culture sprayed into her eyes. Although Pabst had washed her eyes, she had made a terrible discovery: meningitis can infect someone not just through the skin. Pabst was the first woman killed in the line of duty at NIH. Born in Brooklyn, she got her BA and MS from George Washington University. She joined Dr. Sarah Branham’s laboratory at the NIH in 1931, spending most of her time in research on meningitis. Her death at the start of a meningitis epidemic in Washington, D.C. spurred Branham and her colleagues to make seminal contributions to the development of effective vaccines against meningitis. On December 27, 1935, instead of giving a scheduled talk to the American Society of Bacteriologists in New York, Pabst was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery. She was 39.

Asa Marcey’s job was to clean up after the scientists working in NIH Building 5, making sure that everything was ready for experiments each day. In the evening, he would go home to Arlington, Virginia where he lived with his wife, one of his three daughters, his son-in-law, and his three grandchildren. He had served his country during World War I, even though he had been born in 1880 and was 38 during the war. In the spring of 1940, scientists at NIH were beginning to study Q fever, a disease caused by the bacterium Coxiella burnetii. People can get infected by inhaling it or coming into contact with the bodily fluids of infected animals. Most infections are not severe. During ten years of research on Q fever at NIH, some 80 laboratory workers and other staff would come down with it. Marcey was the only one who died, just at the beginning of the studies, on April 25, 1940.

Rose Parrott was the first woman to work at the Hygienic Laboratory (now NIH). She was hired in 1916, a year before the first woman Ph.D., Ida Bengtson, was brought onboard. As Dr. Alice Evans recalled, “Rose Parrott (‘Polly’ to all of us) came to the Laboratory as a nurse to assist in a study comparing raw and pasteurized milk as a food for infants. Her name never appeared on the list of Laboratory personnel, but she was so much a part of the life of the institution that she should have a place in these memoirs. She was young, animated, beautiful, and skillful. With these qualities, of course she was popular. When the study which brought her to the Laboratory was completed, she remained to become an expert technician. She assisted in various investigations until one day in 1944 she became accidently infected with a culture of Pasteurella tularensis. She died of tularemia a few days later.”

While time passes very quickly in Evans’ memoir, Parrott worked at NIH for 28 years on many different investigations including: testing biological products for effectiveness of preservatives and antiseptics to prevent contaminants from making people sick (1918); conducting bacteriological examinations of sewage water in Washington, D.C. (1919); completing the complement titrations for Evans’ publication on antistreptococcal serum (1922); and performing the 275 Wassermann tests necessary for Drs. Charles Armstrong and Ralph Lillie’s work on meningitis (1937). When Parrott died on September 11, 1944 from tularemia that she acquired at work, she was just days away from retirement.

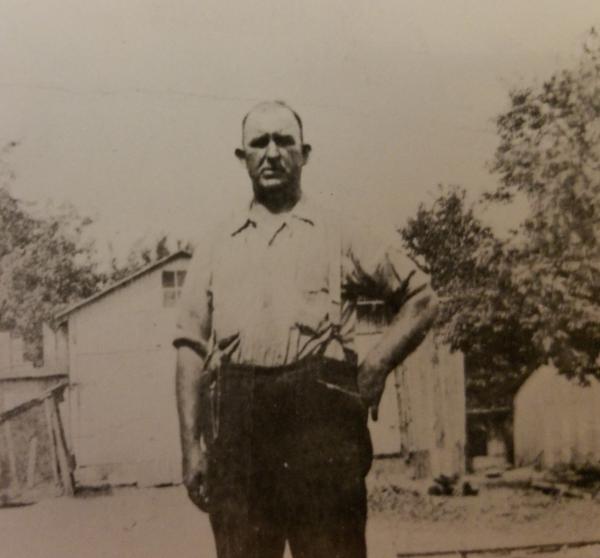

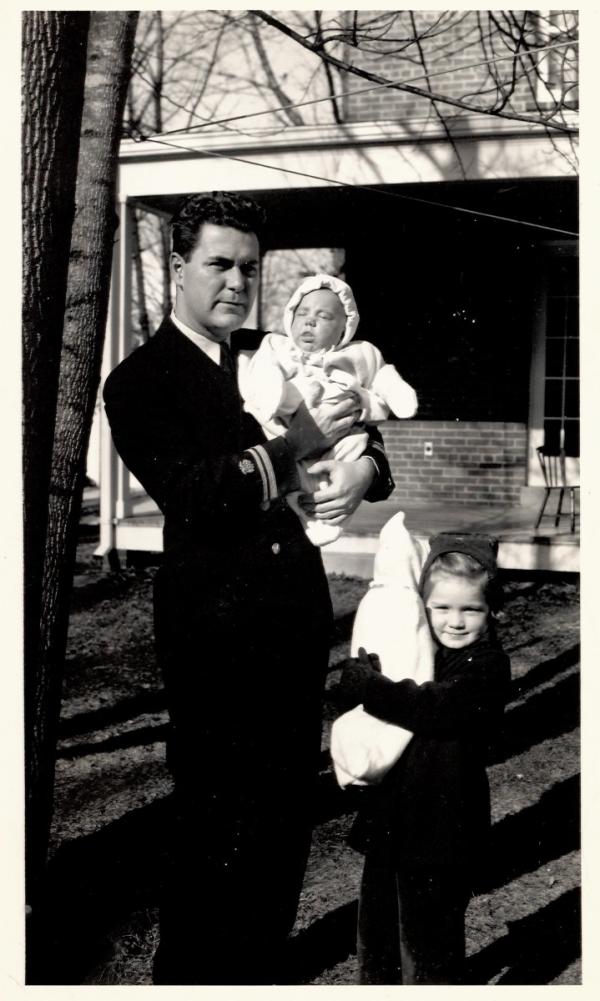

Dr. Richard G. Henderson, wearing his Public Health Service uniform, holds his infant son William while his daughter Sue cradles her doll, about a year before he would die of typhoid fever. During World War II, scientists at NIH developed vaccines for diseases likely to infect our troops overseas. Henderson worked on standardizing typhus vaccine, demonstrating the existence of a toxin produced by epidemic typhus in egg yolk sac cultures (which were used for vaccine development) which enabled the researchers to develop a mouse neutralization test. Henderson and his laboratory aide Leroy Snellbaker both became ill with typhus. Henderson died on October 20, 1944.

The son of an anesthesiologist, Henderson was born in Homer, Michigan on April 29, 1913, but his family moved to Long Beach, California where he attended high school, participating in the school’s music and acting programs. In 1930, Henderson took a tour of Asian countries before heading off to Pomona College (BA 1934) and medical school at St. Louis University. He met his future wife Adele, who was attending nursing school, in St. Louis. Henderson received his M.D. in 1938 and completed his internship at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. The Henderson’s moved onto the NIH campus in the Public Health Service quarters in 1942 with their daughter and infant son. After Henderson’s death in 1944, Adele remarried 12 years later to Dr. Viron Diefenbach, who was in the PHS dental service.

Ultraviolet lights glow eerily in the windows of Building 7 at night. After Dr. Richard Henderson and technician Rose Parrott died within weeks of each other in 1944 of infections they acquired on the job at NIH, Surgeon General Thomas Parran was successful in asking Congress for money to build a state-of-the-art laboratory building designed just for dangerous biological studies. Building 7, known as the Memorial Building, sat across the street from Building 5 where Henderson and Parrott had worked, and opened in 1947.

Building 7 had a laminar air system and superheated grids to sterilize air as it passed through the ventilation system and ultraviolet lights were turned on each night to help sterilize surfaces. Staff entered laboratories only after going through decontamination locks where they showered and changed clothes. The concrete window canopies replaced fabric shades that might become contaminated. Although the building’s safety features never functioned quite as well as hoped, the construction of Building 7 was a belated recognition of the dangers that NIH staff faced, and that the country wanted no more martyrs to science. Building 7 was demolished in 2015.

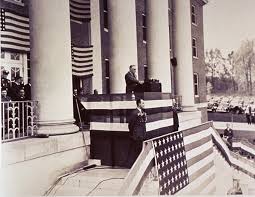

“Today the need for the conservation of health and physical fitness is greater than at any time in the nation’s history. In dedicating this Institute, I dedicate it to the underlying philosophy of public health, to the conservation of life, to the wise use of the vital resources of our nation. I voice for America, and for the stricken world, our hopes, our prayers, our faith, in the power of man’s humanity to man.” President Franklin Roosevelt at the dedication of the NIH Bethesda campus on October 31, 1941. Watch the video at www.youtube.com/watch?v=UrVZblIYljo.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023