New Study Categorizes Biomedical Careers

After postdoctoral fellows in biomedical research complete their training, they are prepared to land permanent positions that utilize their unique research skills. While some may choose the traditional academic route, and become tenure-track scientists, many take posts that keep them engaged in science, but not necessarily doing research.

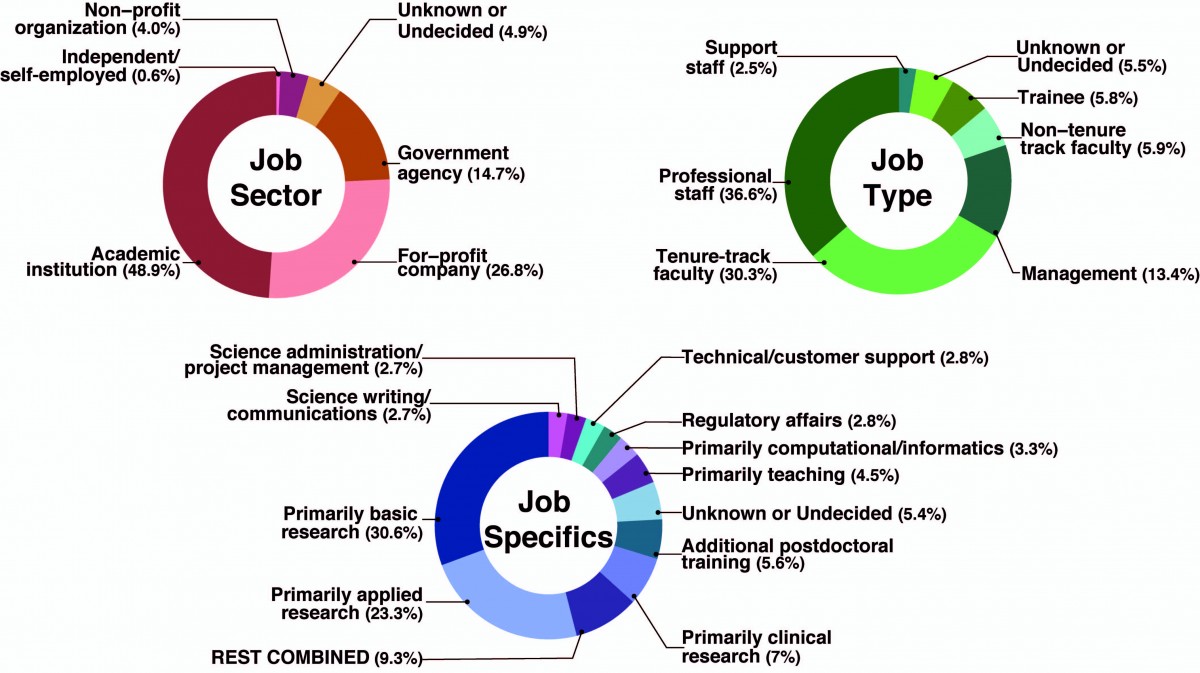

For the first time at the NIH’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), these non-faculty jobs, and the numbers of NIEHS postdocs in them, are broken down in a study that appeared online in the January 15 issue of Nature Biotechnology. The paper discussed a new tool that visualized the kinds of work the former postdocs were doing.

Collins led the NIEHS team in creating a framework that categorizes tenure-track appointments and positions in other occupations.

Tammy Collins, Ph.D., corresponding author of the study and director of the NIEHS Office of Fellows' Career Development, says she and her co-authors compiled job titles and career details for more than 900 NIEHS postdocs from the past 15 years. Of the three categories mentioned in the paper — job sector, job type, and job specifics — Collins considers analysis specifically of job types to be a good gauge for assessing employment levels of scientific postdocs.

"It lets us get a handle on whether our Ph.D.s are gainfully employed or becoming underemployed," Collins says. "It helps us understand how these employment levels may be shifting within academia, industry, and government."

One job type that attracted more than a third of NIEHS postdocs was professional staff. Collins said these positions are mainly mid-level posts that offer more independence and allow young scientists to use their research training. In the case of professional staff in academia, the tool permitted her to classify non-faculty, professional staff such as a person working in a technology transfer office or someone involved in disseminating policy.

But, the beauty of the tool is that it distinguishes people in those roles from the approximately 13 percent of scientists in higher level, managerial roles such as director or the nearly three percent working as support staff.

"Lots of individuals had job titles of president, vice president, or director of global operations for example,” Collins says. "And, while support staff constituted the smallest group, these individuals, such as a lab manager or core facilities scientist, are vitally important, because they help researchers perform the work."

Collins hopes this bottom-up approach on the taxonomy of careers will help all NIH institutes and centers speak the same language.

Credit: Nature Biotechnology

The study categorized career outcomes for NIEHS postdocs by sector, type, and job specifics. The authors envision that this approach will help young scientists make career decisions based on data and not anecdotal evidence.

For more information about the tool, see this article from the NIEHS newsletter, the Environmental Factor.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023