Studying ADHD from Genes to the Brain Connectome

Contributed by an NIH clinical trial participant. Names have been changed for privacy.

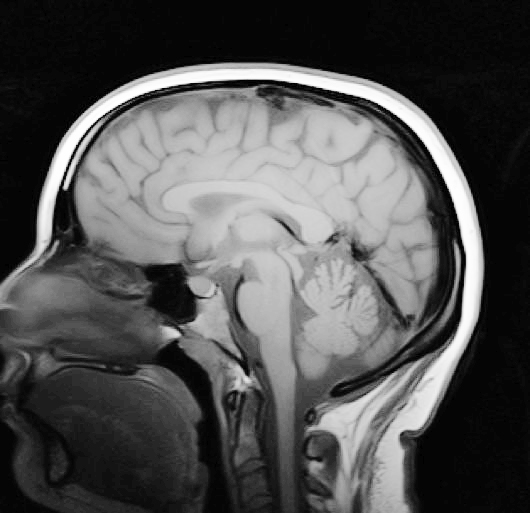

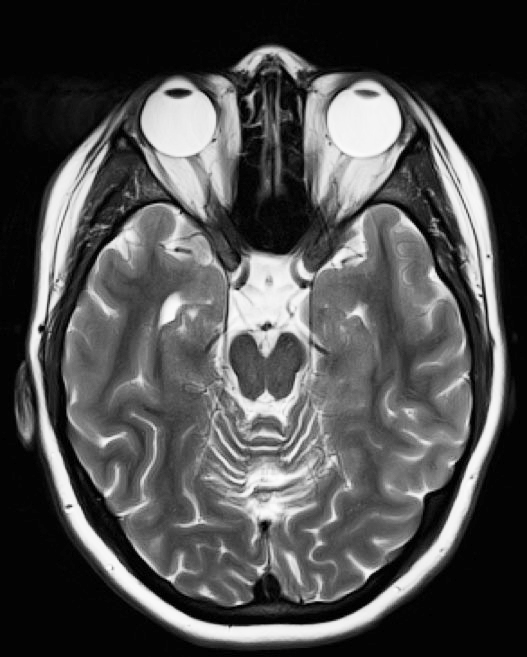

A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of my brain. I had never had an MRI scan before, but found it a surprisingly relaxing experience.

My eight-year-old nephew Luke has a sixth-grade reading level, while still in the third grade. Yet, he often struggles to finish his chores. He carries a timer in his backpack to keep himself on task, both at home and elsewhere. His school provides him with special assistance, including extra time for tests and repeated, detailed instruction from his teachers.

The challenges arise because Luke, like his mother Rebecca, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Rebecca’s life must be highly organized for her to get things done at work and home. Her husband, Steve, has learned to be equally organized for them.

Rebecca and Steve told me they were going to join Luke in an ADHD clinical study at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), led by Dr. Philip Shaw of the NIH Intramural Research Program (IRP). The researchers had asked them to invite more relatives to participate, regardless of whether any of us have ever been diagnosed with ADHD. It sounded like an interesting experience, so I happily said “yes.”

Our visit to the NIH Clinical Center began with consenting to participate in the study. Even though we had already spoken about its various components, Dr. Shaw and his colleagues still walked us through the specifics. Everything was clearly explained, from what we would be doing to what would happen with the data the researchers collected.

When Dr. Shaw asked us if we had any questions, I asked why he had chosen to study ADHD.

“Right now, about one or two kids in every classroom is taking a medication or having an intervention for ADHD,” Dr. Shaw explained. “It is a very common problem. This is a major public health challenge, and it’s something that we really have to pay attention to. And I think it deserves the best science we can possibly do. We need to know more about the biology of ADHD, and that will help us to hopefully develop much more effective interventions to help these kids.”

The NIH defines ADHD as “a brain disorder marked by an ongoing pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development.” It can cause people great difficulties with impulse control, movement, and attention span in school and social situations, as well as in the workplace.

While researchers are unsure of what exactly causes ADHD, they have identified some risk factors. Genes are one risk factor, and that’s where Dr. Shaw’s work comes in.

“We know it’s very, very heritable,” he explained. “It’s probably almost as heritable as things like height, but we actually don’t know very much about the genes that cause this problem.”

The goals of Dr. Shaw’s study are to gather data, including DNA samples, from families in which ADHD is prevalent and try to find the contributing genes.

“Once you know the genes, it points to biological pathways,” Dr. Shaw said. “Once you know those, you can start thinking about novel treatments to help kids and adults.”

Potential future treatments could include new medications, new behavioral interventions, or new combinations of both.

A key aspect of Dr. Shaw’s research involves studying the brain connectome. The connectome is made up of the functional, structural, and physical connections between different brain regions, allowing those regions to communicate and work together.

“The reason for looking at the connectome is that we know if there are people who have problems with attention and problems with impulse control, there are differences in the connectome that may well be contributing to those problems,” Dr. Shaw explained.

His team uses MRI brain scans to visualize and study the connectome in action.

“MRIs are useful,” Dr. Shaw said, “because they don’t involve any harmful radiation at all, so they’re safe.”

Another angle on my brain. I learned during the study that, at this time, the researchers do not believe I have ADHD.

In clinical studies, each step requires informed patient consent, including understanding if and how data may be shared afterwards. With the patient’s permission, his or her DNA samples and other data can be stripped of personally identifying information and placed in a database for other researchers to use in their work.

For Steve and Rebecca, it was a pleasure to contribute in any way that might help people learn more about the condition.

“Knowing more about ADHD would help me learn about my family and help me prepare to be more supportive of Luke,” Steve shared. He also felt that joining the study would reassure Luke that his ADHD is manageable and ordinary, rather than a defect.

After we finished consenting, Rebecca, Steve, and I met individually with a study coordinator to discuss our family and personal histories of medical and mental health, followed by cognitive testing activities. While the adults spoke privately, Luke was kept occupied with some similar testing, which involved letter blocks and worksheets, as well as a short computer activity.

“I liked them,” Luke said of the researchers he worked with. “They were all nice.”

After a break, we provided our DNA samples. The preferred method of taking a DNA sample is to draw blood, since it provides more DNA within a single sample. However, this method was not favored by Luke once he saw the small needle it required. Luckily, the researchers were quick to offer an alternative.

“I was expecting to do a blood draw,” Luke explained to me, "but instead I just spit into a few different tubes. And then it was done.” His parents were also pleased with how accommodating and flexible the researchers were.

“Everyone was wonderful,” Rebecca said. “They had such a great rapport with Luke. Not everyone loves hanging out with eight-year-olds, but they just did a wonderful job with him. I think he had a great experience.”

It was also exciting to learn that Luke may be invited back sometime in the future for additional study participation, since the NIH IRP provides a unique setting for long-term studies and research.

“I think our research benefits from the stability that is so characteristic of the NIH Intramural Program,” Dr. Shaw said. “We have been able to follow up kids for many years. That exemplifies the sort of stability that allows us to conduct these great longitudinal studies.”

The last part of the day was MRI scanning. We were all surprised to find it oddly relaxing, almost like riding in an airplane with a cozy bed rather than a regular seat. Earplugs blocked out the noise of the machine, and a mirror-like device was mounted over our heads so we could enjoy a movie throughout the scan (Luke and I both chose Kung Fu Panda 2).

“Knowing what the study is looking at in terms of genetics and in terms of brain structure, I think it will be really interesting to see how those play into ADHD,” Rebecca said.

Steve and Rebecca are both hopeful that the study findings will lead to a better understanding of ADHD for everyone, not only patients and healthcare providers.

“ADHD is still very stigmatized,” Steve said. “And I think there’s still a lot of confusion about what it actually is.”

The entire experience was enlightening for us all, and we found ourselves very grateful to be a part of it. Luke was astonished after seeing the MRI images of his brain. He felt that more people should participate in NIH studies.

“NIH is a great place to learn, especially to learn about science,” he said. “Another reason people should help NIH is because they help other people. And if they help you, then you can help them by doing the stuff they ask. And if you don’t wanna do that, they have alternatives.”

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, January 31, 2024