A Masterful and Multifaceted Molecule

TGF-beta Research Bridges Basic Science and Clinical Promise

In the early 1980s, a discovery at the NIH revealed a protein that would forever change our understanding of cell signaling, development, and disease: Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta).

Initially investigated for its role in spurring cancer growth, TGF-beta has since emerged as a key player in a wide array of biological processes, from how cells develop to why some tumors are resistant to treatment. What began as a promising lead to fight cancer has since grown into a rich and diverse field of study, with NIH research continuing to lead the charge in unraveling the complexities of TGF-beta signaling and its role in human health.

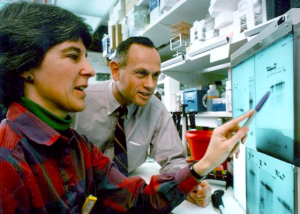

NCI

In the 1980s, Anita Roberts and Michael Sporn discovered TGF-beta's complex effects on cancer cells, wound healing, and immunity.

TGF-beta origins

At the bench of the TGF-beta discovery were the late Anita Roberts and Mike Sporn, along with their NCI colleagues, who noted the protein’s ability to confer oncogenic properties onto otherwise healthy cells.

The finding built on concepts already proposed at NCI that hormone-like growth factors could spark the development of unchecked malignancies (PMID: 7412807). Even earlier work uncovered the origins of oncogenes, or genes that could trigger cancer when activated (PMID: 176594). That discovery earned the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1989 for Michael Bishop, a former NIH postdoc who built his career at the University of California, San Francisco, and Harold Varmus, also a former NIH postdoc who moved to UCSF and who would become NIH director and then NCI director.

While termed a growth factor, TGF-beta is a cytokine—a class of critical proteins that broker communication between cells and coordinate proper immune function. Depending on what’s happening in their environment, they dock to specific cellular receptors and can set in motion a cascade of events that modify how genes are expressed and what proteins are produced.

So, in 1983 the NCI scientists took on the challenging task of isolating and purifying high yields of TGF-beta from human blood platelets and distributed it freely to scientists both at NIH and around the globe. What ensued was a new field of research.

“Sporn took TGF-beta and gave it to a lot of different people and said ‘you should try this in your biological system. I’m sure it will have an effect,’” said Lalage Wakefield, who joined the Sporn lab in 1983 and is now a senior investigator in NCI’s Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics.

It soon became apparent that TGF-beta had many functions in regulating biology (PMID: 3871521), and that its activity heavily depended on the context in which it was acting, such as the target cell type and the microenvironment.

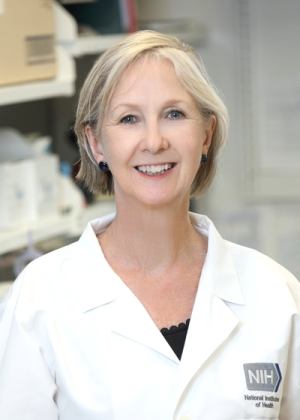

LALAGE WAKEFIELD, NCI

The Wakefield lab developed a new transgenic TGF-beta reporter mouse that researchers can use to study all the biological pathways influenced by the master molecule. Body systems in bright green indicate TGF-beta activity.

According to Wakefield, this notion of contextuality was one of three important concepts that came from the Sporn lab’s early research about how growth factors behave. The second was the autocrine hypothesis, which posits that one cell can emit signals that can act back on that same cell and render it somewhat independent from signals in the microenvironment. And third was the notion that a growth factor could be multifunctional.

For example, a dogma in the field is that TGF-beta serves a complex dual role in carcinogenesis: It can function primarily as a tumor suppressor early on and then switch to promoting tumor growth as a cancer progresses.

TGF-beta is also a potent immunosuppressive factor. Investigators in the lab of Anthony Fauci, then director of NIAID, were the first to show TGF-beta’s inhibitory action on T cells (PMID: 2871125). The molecule’s immune-manipulating mechanisms continue to be studied today to design targeted immunotherapies that could treat conditions such as chronic inflammation, autoimmune disease, and cancer. Such work is underway at NIDCR’s Mucosal Immunology Section, led by senior investigator Wanjun Chen (PMID: 28423340).

Wound healing and fibrosis are yet more processes with TGF-beta’s fingerprints all over them. Pioneering work by Roberts and colleagues demonstrated that the molecule plays an integral part in tissue repair by stimulating collagen production (PMID: 2424019). Roberts continued to contribute extensively to the field and is now the third most cited woman scientist in the world, according to Michael Gottesman, senior investigator at NCI’s Laboratory of Cell Biology.

NCI

Lalage Wakefield

Current NIH research expanded on the fibrosis concept, showing a potent effect of TGF-beta signals in promoting adipose tissue fibrosis as a precursor to metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes (PMID: 39461664). Indeed, inhibiting TGF-beta’s actions in mice improved the deleterious effects of metabolic disease by improving adipose tissue function (PMID: 21723505; PMID: 30100246). “The findings open up a potential utility of anti-TGF-beta therapies for these conditions,” said Sushil Rane, NIDDK senior investigator and corresponding author on those studies.

As the field matured, several other findings would emerge from NIH labs. Those included the development of one of the first TGF-beta knockout mice, confirming the protein’s importance in immunomodulation (Stefan Karlsson); SMAD knockout mice, which lack the gene needed for signaling by TGF-beta (Chuxia Deng); and the solution of the molecular structure of TGF-beta (David Davies).

Modeling the molecule in cancer

“I think of TGF-beta as a sort of fine-tuning knob on the top of other more fundamental biologies,” said Wakefield, whose name can be found on many of the original papers describing its myriad functions. Her lab now develops preclinical models to investigate the dual role of TGF-beta in breast cancer.

Her team demonstrated in mice that a lifetime exposure to a TGF-beta antagonist could protect against metastasis without adverse side effects, showing the feasibility of targeting the growth factor in cancer (PMID: 12070308). “Most of that benefit seems to come from reactivating antitumor immunity,” said Wakefield, noting that they’ve also seen deleterious effects in a small fraction of their models. “We think it relates to taking the brakes off the cancer stem cells. So, we’re using these preclinical models to develop predicative biomarkers that allow you to determine whether a patient will respond positively or adversely to these treatment strategies.”

Wakefield knows the field deeply, having been in the TGF-beta trenches longer than almost anyone on the Bethesda campus, and her team is excited to share a new tool with colleagues. “The coolest thing we’ve developed yet is a transgenic mouse that reports on TGF-beta signaling with a green fluorescent protein. You can see all the tissues that the TGF-beta pathway is active in lit up in green,” she said. As you might imagine, there’s a lot of green.

Transgenic mice are mice that have had DNA from another source put into their DNA. The foreign DNA is put into the nucleus of a fertilized mouse egg. The new DNA becomes part of every cell and tissue of the mouse. These mice are used in the laboratory to study diseases. Learn more.

All in the superfamily

From an evolutionary perspective, TGF-beta is thought to have evolved when animals were becoming more complex and was perhaps needed to coordinate among all the different cells that had to function together. It’s a founder molecule for a much bigger superfamily that includes structurally similar bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and activins, all of which play key roles in modulating normal development and maintaining homeostasis.

Uncovering how those molecules regulate development is Mihaela Serpe, senior investigator in NICHD’s Section on Cellular Communication, who exudes a zest for diving into the deep end of the basic science behind complex cellular signaling. A biochemist by training, Serpe has been involved in TGF-beta research since her postdoctoral days when, coincidentally, she shared a post-conference cab ride back to the airport with Anita Roberts—along with a cherished conversation about cellular signaling.

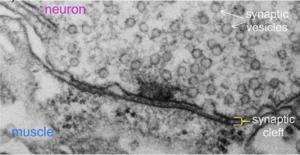

MIHAELA SERPE, NICHD

Electron micrograph of a single synaptic junction in the fruit fly Drosophila. Studying how molecules in the TGF-beta superfamily influence the development of such cellular junctions helps researchers to better understand normal human biology and can hint at therapeutic targets in disease.

Today, her lab studies the interplay between various BMP signaling pathways and the development of neuromuscular junctions using the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. “Drosophila became a darling in basic science for TGF-beta because of fewer signaling components and powerful genetics,” said Serpe. Teasing these pathways and their different biological outcomes is important because they overlap with those in humans and are critical in maintaining the integrity of cellular junctions.

They defined a novel and nuanced positive feedback mechanism involving BMP signaling pathways whereby active neurotransmitter receptors signal to their controlling motor neuron that they are working hard: Consequently, those synapses receive reinforcement. It’s a sort of “use it or lose it” phenomenon (PMID: 26815659). Furthermore, the BMP components engaged in that synapse-strengthening signal become unavailable for retrograde signaling, which controls growth. In essence, motor neurons use different BMP signals to balance their act: They sample their surroundings then choose between building more synaptic junctions or reinforcing the existing ones.

Such discoveries hint at therapeutic targets for a group of human diseases that disrupt cell–cell integrity and can result in malformed brain or heart vessels. “If a disease is due to skewed BMP signaling, you need to figure out first what kind of BMP signaling is perturbed,” said Serpe. “And if we know the specific pathway and how to tamp things down and restore the balance, then we might have a way of solving the problem.”

Serpe’s lab has since identified mutations that unevenly disrupt various BMP signaling pathways (PMID: 32737119), and it is about to study new mutant flies that it has developed to understand the basis of several human diseases that affect the integrity of cellular junctions.

Countering cancer’s defenses

Treatment-resistant cancers may have an adversary coming. Claudia Palena, a senior investigator at NCI’s Center for Immuno-Oncology (CIO), uses preclinical models to find new combinations of drugs that break down cancer’s defense mechanisms.

“We're trying to understand what we can do in terms of the mechanisms of resistance that are at play in the tumor microenvironment to improve the response to treatments,” she said. CIO preclinical labs work closely with their clinical colleagues toward the goal of bringing those strategies to patients.

One of those strategies is inhibiting TGF-beta with agents such as bintrafusp-alfa, a dual-function fusion protein that blocks the PD-L1 protein and captures TGF-beta within a tumor. Some cancer cells express PD-L1 to nullify the body’s T-cell attack, and blocking the protein is behind how immunotherapies known as checkpoint inhibitors work. However, they don’t work for everyone, and part of the reason might be because of TGF-beta’s immunosuppressive influence within some tumors. Foundational research at CIO labs found that bintrafusp-alfa indeed had antitumor properties by making cancers more susceptible to the body’s immune defenses and treatments such as chemotherapy (PMID: 32079617).

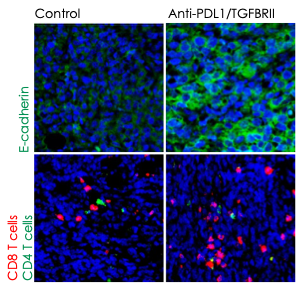

JOURNAL FOR IMMUNOTHERAPY OF CANCER, NCI

Preclinical work at the CIO showed that blocking TGF-beta and PD-L1 with the dual agent bintrafusp-alfa allowed immune cells to more effectively infiltrate and attack tumors. Immunofluorescence images above show increased epithelial cadherin, a protein that can act as a tumor suppressor (top panels, green signal), and increased CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell activity (bottom panels, red and green signal, respectively) after treatment.

Bintrafusp-alfa has been discontinued by its manufacturer, but the drug did make it to clinical trials and could inform future therapies. Led by James Gulley, codirector of the CIO and NCI clinical director, a first-in-human trial used the compound to treat several types of previously treated advanced solid tumors and showed early signs of efficacy (PMID: 29298798).

CIO clinical teams then expanded the approach with encouraging results. For example, treating human papillomavirus-associated malignancies with bintrafusp-alfa showed promise (PMID: 33323462). “These data suggest a response rate that is about twice the response rate of [a checkpoint-inhibitor alone] in the same patient population,” Gulley told the Catalyst. In patients with non-small-cell lung cancer, the compound was relatively well tolerated and showed modest clinical benefit (PMID: 36571770; PMID: 38485188). Yet other studies investigated the drug’s mechanisms in head and neck tumors (PMID: 32641320).

A multiagent strategy looks to be more effective. These are early days for such therapies and research into blocking TGF-beta in the context of immunotherapies continues: Combining several different molecules that disrupt distinct components of cancer’s defense arsenal resulted in robust antitumor responses—and even tumor cures—in some preclinical models of breast and lung cancers that were resistant to checkpoint inhibitors alone (PMID: 32188703; PMID: 35230974).

“The interaction between the clinical and the preclinical work is so important,” said Palena, whose lab is actively researching new combinations of immunotherapeutic agents. “As we learn more, such as what tumors have high levels of TGF-beta, we can then come up with ideas of how to block it with this multiagent approach. We expect that, hopefully, we keep developing these strategies to eventually bring to the clinic.”

TGF-beta interest group reactivated

Are you interested in more TGF-beta? After a pandemic-induced period of quiescence, the TGF-beta Superfamily Interest Group (SIG) is reinvigorated and welcoming new members from inside the NIH and out. It hosts monthly meetings, shares expertise, and showcases what’s happening on campus to provide support and mentoring for people working in the TGF-beta field.

“We are talking with each other and sharing reagents, we can keep that information alive and share that with our trainees,” said Serpe, co-chair of the SIG along with Christina Stuelten(NCI) and Rane, who studies TGF-beta’s role in metabolism. “There’s a lot of cross-talk here from development to cancer biology, and that is something that we are trying to foster right now.”

Join the TGF-beta SIG mailing list.

Read about the honorary Anita B. Roberts Lecture Series and listen to past talks highlighting the outstanding research achievements of women scientists at NIH.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, March 19, 2025